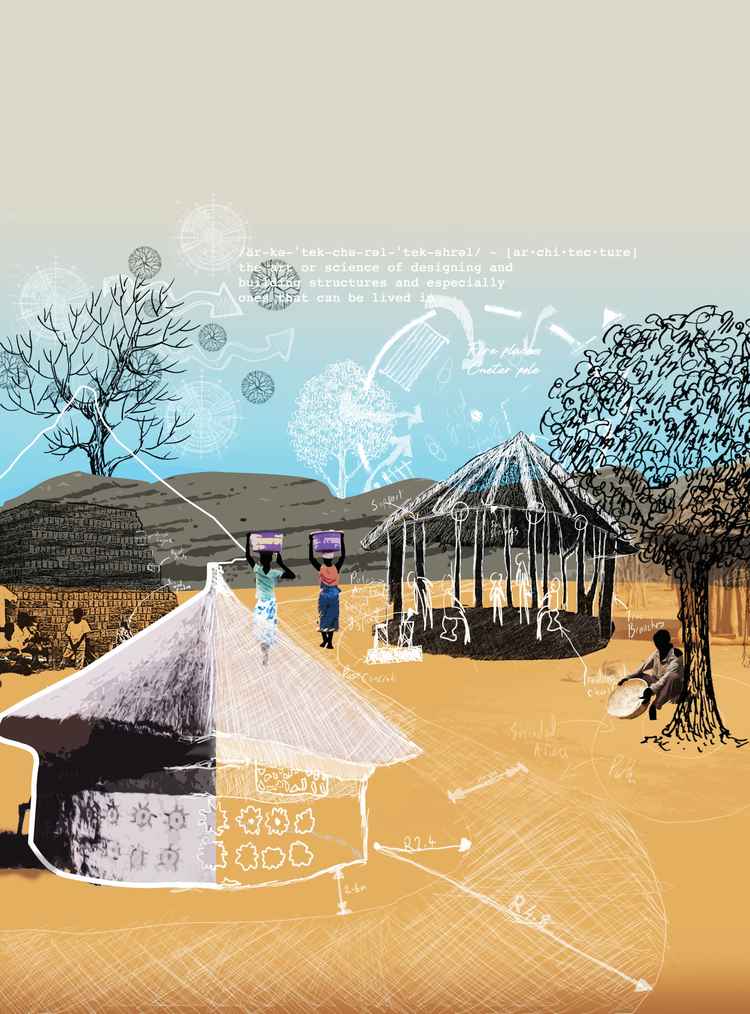

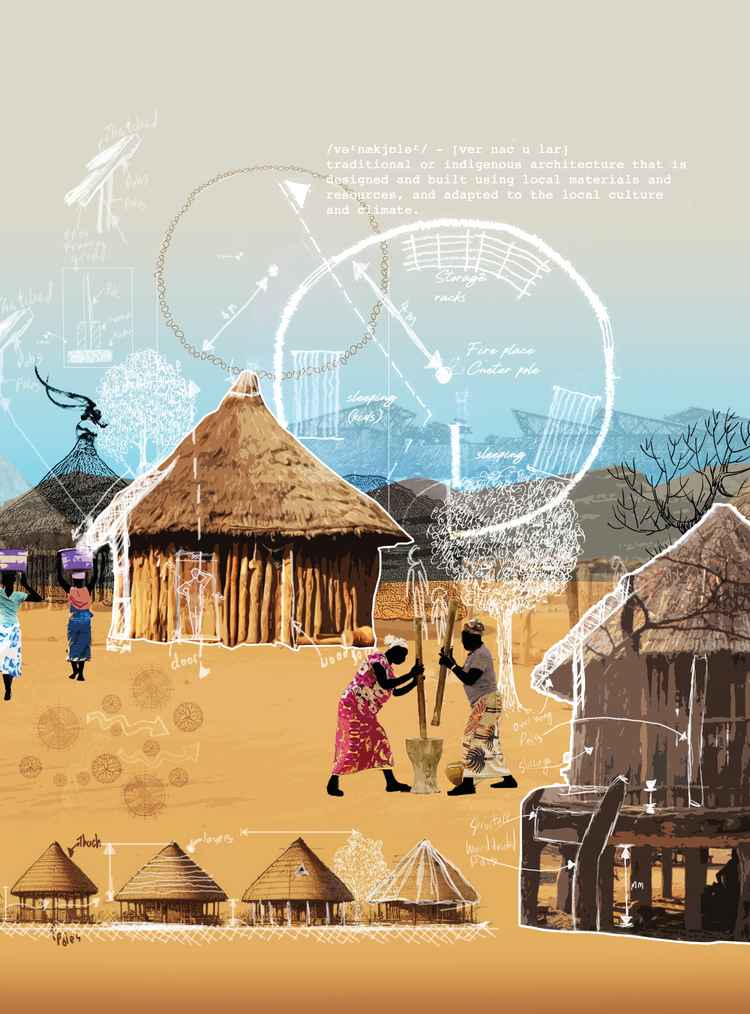

Zambia has a rich cultural history reflected in diverse vernacular architectural styles. These styles give the nation a unique architectural identity rooted in the larger Bantu culture of Sub-Saharan Africa. Vernacular architecture in Zambia is deeply influenced by the environment, climate, culture, art, and social context in which it is built. These structures are both practical and symbolic of the communities they serve.

The Roots of Vernacular Architecture in Zambia

The colonisation and Christianisation of Zambia, which began in the late 1800s, brought a distinct architectural style that is more prevalent today. In the northern and western parts of Zambia, where Christianity first penetrated the country, modular matchbox houses made of clay bricks, wide windows, rectangular verandas, and thatched or corrugated iron roofs became common. These houses often incorporated all utility spaces—cooking, living, and sleeping—under one roof, reflecting Western architectural influences introduced by missionaries.

The problem arises from the one-size-fits-all approach that the implementation of modern Western architecture adopted. In contrast, traditional design approaches in Zambia are responsive to the local climate and incorporate community-oriented spaces and community compounds, better suited to the community-driven, social context still prevalent in Zambia today.

Building with the Environment

Zambia's vernacular architecture is heavily influenced by the environment, which provides the materials used in construction. Traditional architecture relies primarily on three main elements: soil, trees, and wild grass. In contrast to modern building methods that transport materials across vast distances, vernacular architecture uses locally sourced, renewable materials, creating structures that are deeply connected to the environment and culture.

Zambia is home to vast forests and in most parts of Zambia, structures are typically framed with poles made from local trees, mainly hardwoods like Mopane and Mukwa, which are preferred for their naturally termite-resistant properties. Alternatively, the poles may be burnt or beeswax applied to increase their pest resistance. In grasslands like the Barotse Plains or Bangweulu Swamps, reeds and sun-dried soil bricks often replace wooden poles.

Earthen walls are constructed from carefully selected clay found in dambos or anthills. This clay is used to form the walls that cover pole frameworks. Circular structures are typical of Zambia's vernacular style, with smaller, flexible branches, called imbalo (small branches) in Tonga, used to shape the curved earthen walls. Or the clay may be formed into bricks and sun-dried or baked in ichibili or traditional kiln, in Bemba. Mud floors are often varnished using cow dung, while ash is mixed into the lower parts of the walls to act as a natural insect repellent.

Vernacular African architecture is often associated with conical thatched roofs. In Zambia, these roofs are made from different types of wild grass. The most common is elephant grass, known as lenje in Western and Central Province, from which the local people, baLenje - people of the grasslands, derive their name. Chilenje refers to the place where the grass is grown and harvested. The grass is layered onto a roof frame, tapering upwards into the distinct conical shape and secured with tree fibres called nzinzi in ciChewa. Thatch maintains a comfortable internal temperature due to its high insulation properties, making it ideal for Zambia's tropical climate. The overhanging roofs offer protection for the earthen walls, keeping them dry during the rainy season.

Social Status and Decoration in Architecture

In many Zambian tribes, architecture is closely linked to social status and cultural traditions. Roofs and walls can be adorned for aesthetic purposes or to indicate the status of the occupants. For example, among the Ila people of Southern Zambia, earthenware and animal horns or skulls are placed on rooftops to signify the influence of chiefs or principal wives.

The most intricate thatched roofs are found among the Luvale, Mbunda, and Lunda people in Northwestern Province. These thatched roofs are often decorated with fibres, creating elaborate designs or patterns for aesthetic and symbolic purposes. Earthen walls may be decorated with tribal paintings and depictions made by women, using natural colours from soil, charcoal, ash, and vegetation. In some regions, the ash of Mubala and Mutundwa trees produces a striking, pure white colour, while coloured soils called inkanka in Mambwe are sourced from riverbeds, anthills, and dambos. Each colour holds deep spiritual or historical significance for that community. This art form is known as kukuluba in Ngoni and kusona in Luvale.

Building in Response to Climate

Climatic conditions have great influence on vernacular architecture. Zambia has a friendly climate with three distinct seasons – a prevalent hot, dry season; a short rainy season; and an even shorter cold, dry season. This allows most homestead activities to be done in the open or beneath semi-open structures for most parts of the year.

In the Gwembe Valley, homes known as balangwa are made with walls constructed only from widely-spaced poles, allowing cross-ventilation while offering a view inside the home. A variation of balangwa is ingazi, built on stilts to maximise airflow in response to hot weather prevalent in the region. Ingazi is often surrounded by a verandah called dalanze (to sleep outside), which is used as an outdoor sleeping area during summer. Parts of the dalanze are reserved for drying food or wet cooking utensils. The space beneath ingazi provides a shaded working or meeting area, offering respite from the day's heat.

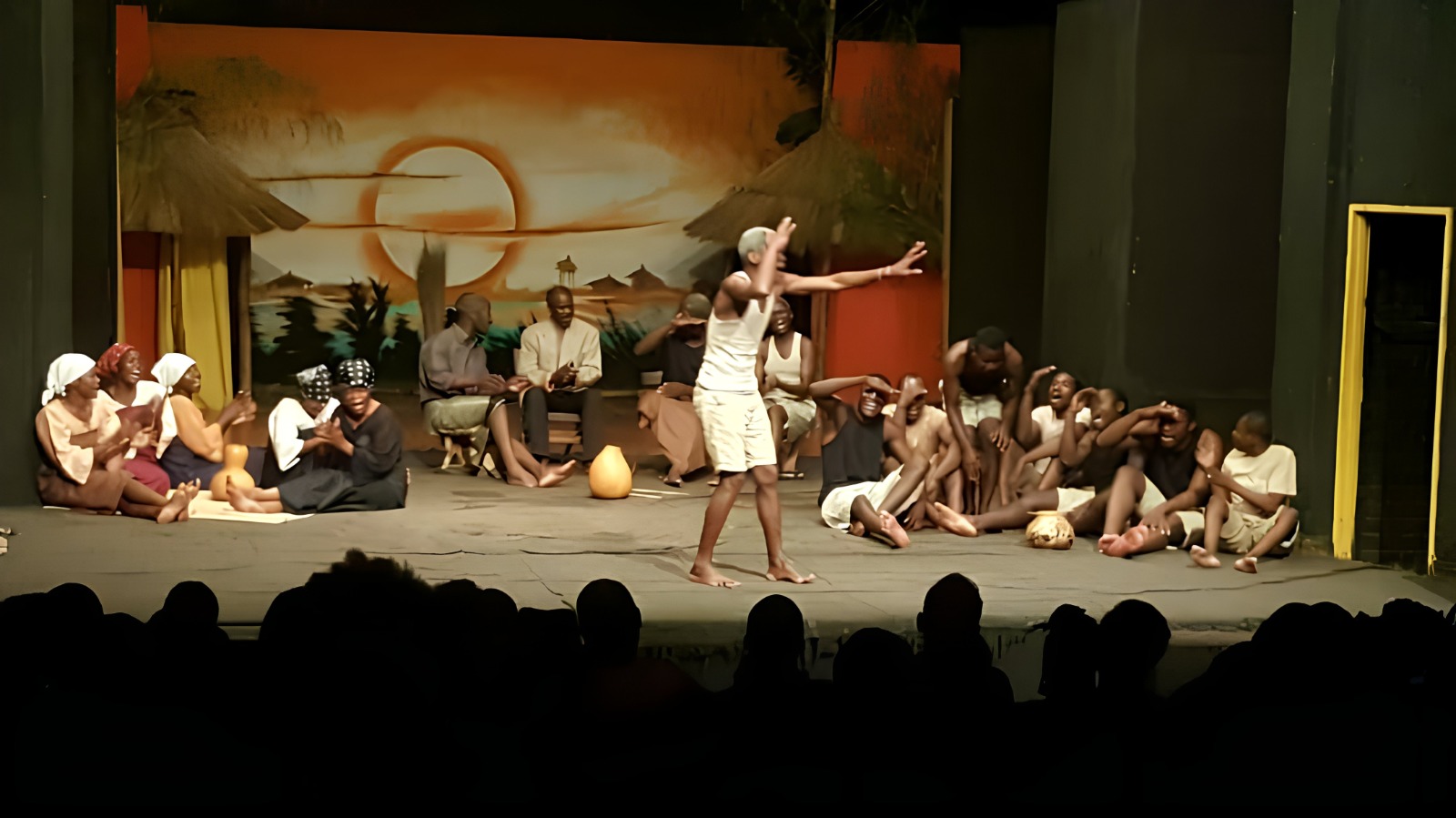

As such, most communal activities in compounds and villages occur in semi-open structures, insaka in iciBemba. Built simply with widely spaced poles, with or without a low mud wall surrounding it and a roof, insaka is used as a dining area, living room, meeting place, and workspace predominantly by men. Women will utilise the verandah under the overhang roof of the main house, known as lukolo in ciChewa, as a workspace or a resting space for afternoon naps in summer.

Social and Cultural Contexts of Vernacular Architecture

Culture also plays a significant role in determining how structures are built and who is involved. Culturally, homestead activities are distinctly divided into public and private tasks, with public chores carried out in semi-open spaces and private activities taking place within the more enclosed, private spaces.

The kitchen, while smaller, is built similarly to insaka with large openings between the roof and the walls to allow smoke from the cooking fires to escape. The kitchen is used for cooking and eating by women and children. The kitchen roof often doubles as seed storage, while the smoke from the cooking fires protects the seed from infestation. However, in some parts, specifically Tongaland, kitchens may exhibit full height earthen walls with shelves and storage enclosures constructed as part of the walls.

In vernacular architecture, the sleeping quarters, often regarded as the main house, feature full-height walls that offer greater privacy and protection. These structures are characterised by traditional windows—small openings located high up near the roof to facilitate ventilation. In Lamba, these windows are known as nsokoloto, and their shapes vary between triangular and square, depending on the design. The nsokoloto also serves a dual purpose as storage, with tools like hoes and axes being hung by their blades within the opening. Collectively, these structures, insaka, balangwe, ingazi etc are referred to as n’ganda (the house), embodying the concept of home in a broader cultural sense.

Responding to Economic Needs

Vernacular architecture also addresses Zambian society's economic needs, particularly in terms of food storage. Grain bins, known as nkokwe in ciChewa, are essential for storing staple crops such as sorghum, millet, and maize from one harvest to the next. Raised on stilts to protect the grain from insects and moisture, these bins feature a thatched roof to shield them from rain.

Among the Tonga people, grain bins are sometimes plastered with mud to form airtight structures that prevent infestation. A smaller version of these bins, called ka bule, is used to store groundnuts.

Urbanisation and the Threat of Homogenisation

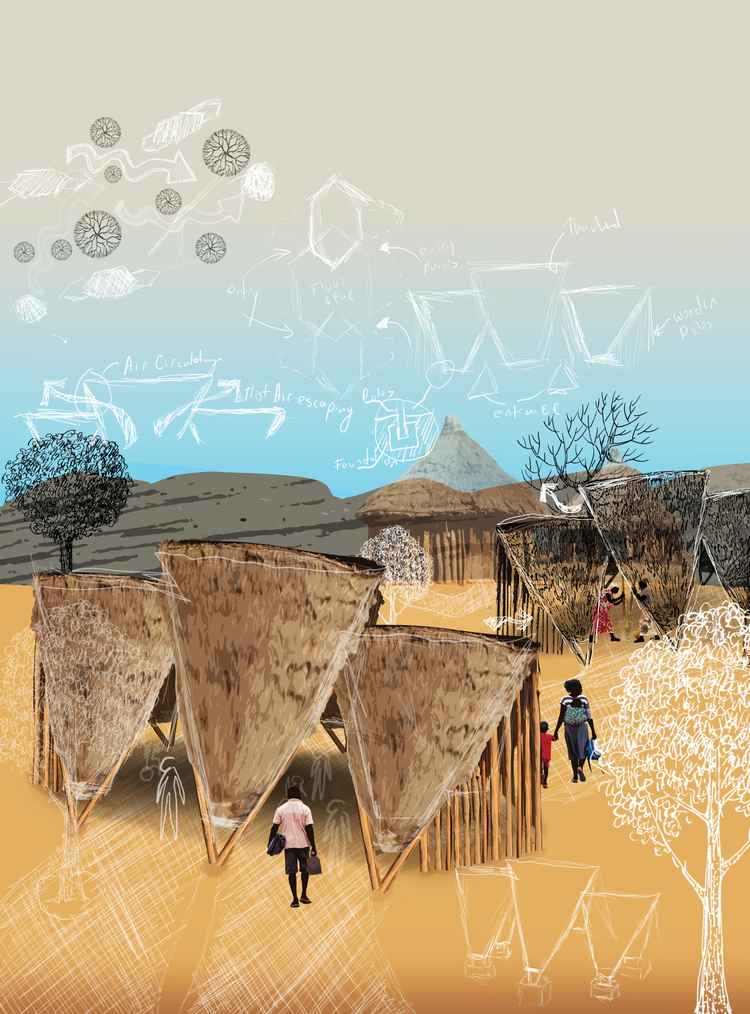

As urbanisation spreads, Zambia's unique vernacular architecture is increasingly at risk of being replaced by uniform, concrete structures that do not reflect local culture or social values and completely disregard the local environment. This shift towards foreign building practices threatens the diversity and identity of Zambian architecture. However, there is an opportunity to integrate vernacular principles into modern urban development, creating sustainable, cost-effective structures rooted in Zambian identity.

Vernacular Architecture and Sustainability

Blending vernacular architecture with modern practices has the potential to create a distinct Zambian architectural style that addresses contemporary needs while maintaining cultural identity. Vernacular design principles offer a sustainable path forward in an era of climate change. Zambia can build structures aligning with global sustainability goals. The inherent climate control abilities of renewable, locally-sourced natural materials are preferable to artificial energy-consuming methods. Vernacular design principles also promote healthier living by reducing congestion and incorporating open spaces, which have become especially important in the wake of pandemics like COVID-19.

Town planners could take cues from the communal compounds of rural Zambia to design cities that promote interaction and community well-being. Integrating semi-open communal spaces and green areas into urban environments would create happier and healthier living conditions. Integrating community spaces like insaka into urban design could also lead to more engaged, happier communities, where social interaction is prioritised in the city’s layout, bridging the gap between rural traditions and urban necessities.