In this poignant tribute to Martin Abasi Phiri (1957-1997), the late Zambian artist, lecturer and founder of the Visual Arts Council of Zambia, and activist Through vivid recollections and exhibition context, the piece draws parallels between Phiri’s life and Zambia’s own coming of age, situating him as a post-independence visionary whose creativity helped shape a national identity.

Martin Abasi Phiri is dead.

He did it. I want to congratulate him, shake his hand just as they did when he graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing. For most of us, death is a threatening promise that whispers over our shoulders like a persistent shadow.

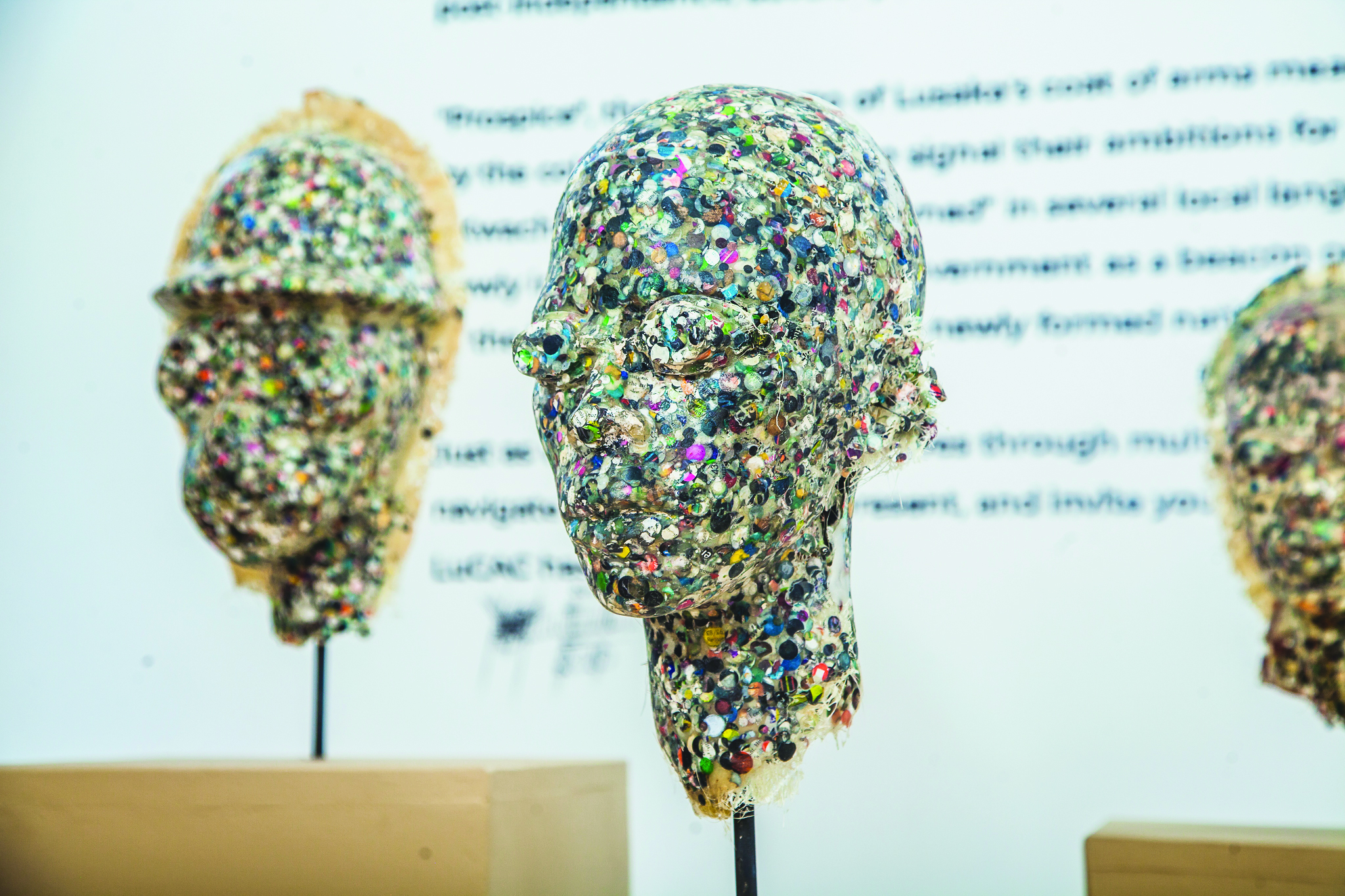

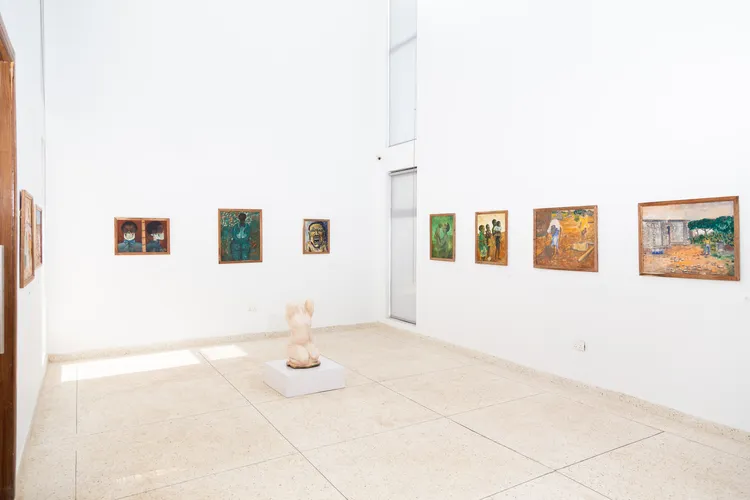

The newly commissioned Martin Abasi Phiri (MAP) Studio at the Lusaka Contemporary Art Centre (LuCAC) is alive with scent and purpose – fresh paint, concrete, and the ambition of young artists. Its inaugural exhibition, “Viable Visions”, curated by Chinese artist Lifang Zhang in collaboration with LuCAC and the Zambia National Visual Arts Council, is a retrospective celebrating the life and work of the late Martin Abasi Phiri.

As a child of the 90s, death is a familiar friend; the kind that asks for cups of sugar they never return. Death visited our homes in a damp, cold gust that made the grown-ups take the couches out to the lawn when their friends, our aunties and uncles, were swept away. It was HIV first, innocuously called ka doyo in a way that made me suspicious of the tiny black ants carrying down crumbs from the kitchen door. Then it was TB, heaving and pulsing behind rooms we were not supposed to enter until the people inside were dead. Then COVID-19 and the obsessive handwashing, and last, the cancer sitting among us and within us, waiting to bloom or be passed down. My father was the last to drop among them and sometimes I wonder who is next.

The white shelves in the MAP Studio carefully exhibit his life’s work. Lifang Zhang ensured that it was the kind of body viewing everyone deserves. Behind the glass is a fresh post-colonial General Certificate of Education from high school, with the newly minted Zambian Coat of Arms. My father has a certificate just like this one. I have never understood why we have cobs of maize instead of guns on the emblem of identity, but I resolve that Zambians were made to have food security. At the time, agriculture was a message, and scholarships were sprayed like confetti over promising citizens. The Chongwe Boys Secondary School of 1980 had a Cambridge Examination; I imagine it abounding with brilliant boys ready to become men. Today, education quality has eroded. Our Chongwe Boys probably think the Queen is still alive.

Behind the glass is a medical certificate and a bursary award letter – I assume both are real. I paid K150.00 to be declared healthy on paper and I receive a K818.00 pay deduction on the bursary loan that was once a grant. I pay willingly. UNZA gave me grit, patriotism and a lewdness one only gains in the place where they lost their virginity.

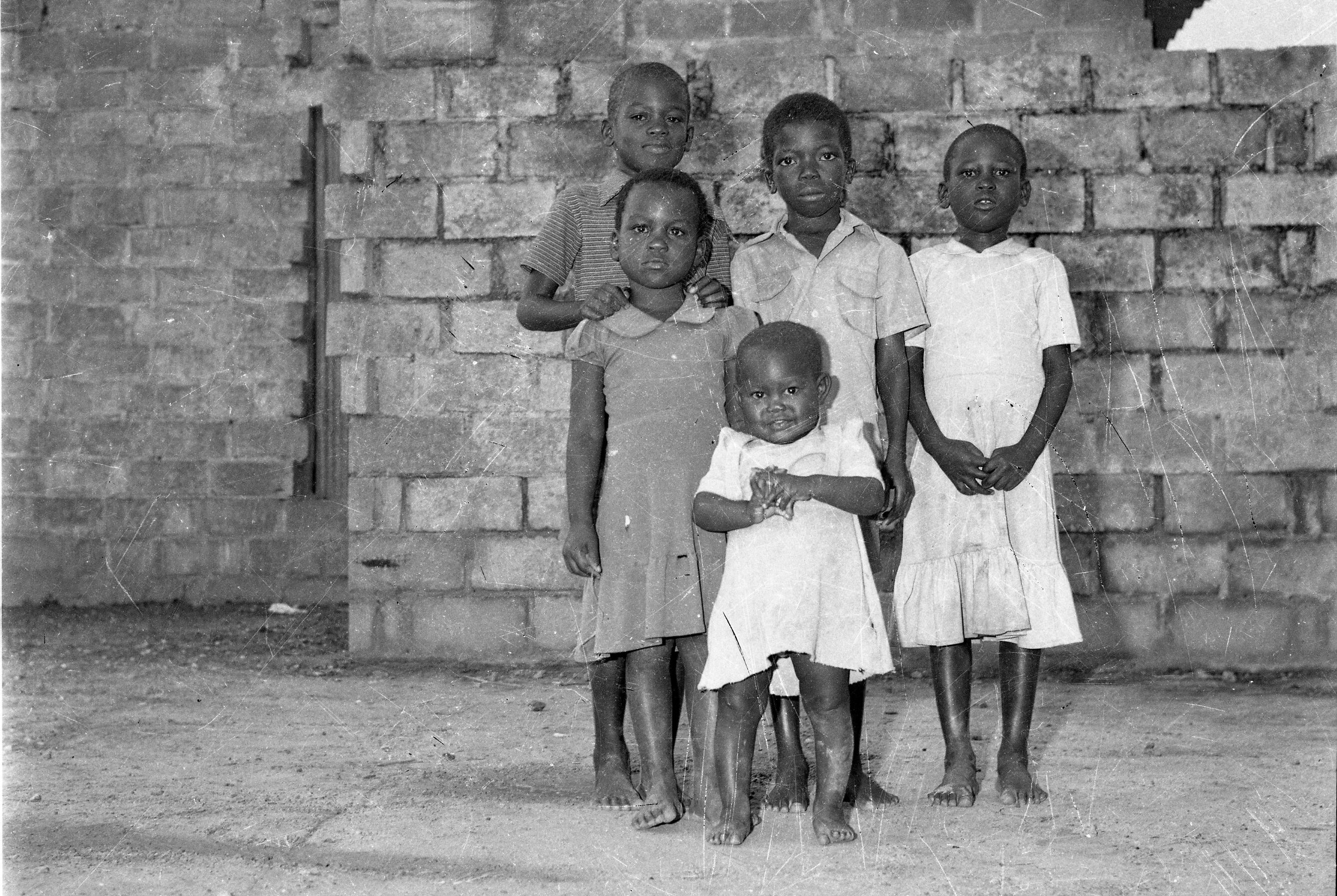

In the photographs, Martin looks like my father in the 80s. They both served their National Service at the same time, shared the same afro, glistening dark skin and optimistic smiles. I wonder if they passed each other in the streets and nodded hello, or if they bought their skinny belts and bell bottoms from the same stores. They were young Zambian men standing on the same foundation.

After graduation in China, Martin comes home and works at delivering the Ngoni Warrior sculpture from his final year project. He goes on to found the Visual Arts Council and pioneers a new wave of artistry. After graduation, my father comes home and makes a baby – Ben, named after him. He goes out again, this time to Oslo, in the same winter puffer jacket as Martin. I imagine every nation outside Zambia as full of snow. When my father returns, he makes a baby – me.

Martin has a brother and I wonder about his children, and what it was like growing up under the shade of a Mukwa. Martin writes letters that are now exhibited behind glass – his feelings frozen and timeless, expressing the devotion, hardship, and faith of love at such a time. My Sweet Susan. Dear Sue. His vine is to hold it all down while he manages the tight schedule of his education and artistry. I want to ask Sue if it was worth it.

I wonder about a man who can look at nudity in China while everyone back home is covered in the proper shroud of colonialism. He undresses by taking things apart, down to the sum of their parts. A torso is a rectangle, a chest a triangle, a head is a circle and breasts are semi-circles. Seen as shapes, my mouth doesn’t water with lust.

As prosecution witness #88, Martin Phiri is called upon to testify in the Presidential Petition of 1997. The case – Lewanika & Others v Frederick Jacob Titus Chiluba (1998) – revolved around a constitutional challenge to the eligibility of President Chiluba, who had been elected in 1996. Petitioners argued that Chiluba and his parents were not Zambian by birth or descent, citing his alleged birth in the Belgian Congo (now the DRC).

As a senior lecturer at Evelyn Hone College, Phiri was a master of the human form. Taught to see a man as the sum of his parts, he was called upon to draw the line – literally – between Frederick Titus Chiluba and his lineage. In an age before DNA, Phiri used art and science to demonstrate the study of ageing. Through the drooping of cheeks, the timely enlarging of the nose, the shrivelling of the upper lip – we see the effect of time on both the father and the alleged son. Martin Phiri testified to what he knew. This is what happens when branches of the same tree race through time.

My father didn’t grow old.

Neither did Martin Abasi Phiri.

“An expert witness in the ongoing Presidential Election Petition, Martin Phiri is dead.” -The Post Newspaper, 18 May 1997.

In one of his last works, The Casket, the life and death of Martin Phiri is preserved. The memorial exhibition at LuCAC is a summation of Martin’s parts. The teacher in him is seduced into showcasing his process – drawings of everyday life. His warning about climate change is hidden in The Warming Earth of 1989. He paints Rembrandt yellows, a surrealism borrowed from Van Gogh’s work and Edvard Munch’s The Scream, are implanted with large, open African features in his rendition – except Phiri’s scream is outward, while Van Gogh’s struggle was inward. O’Keeffe’s flowers are transformed into Sub-Saharan roses; Da Vinci’s hand of God reaches down to give, not judge.

The piece that ends up in The Casket starts as a self-portrait wooden sculpture hanging in his home before it becomes a joke between brothers. His brother runs with the joke, developing an allegorical video installation of the Zambian funeral. The wooden portrait is placed in a metal casket made of recycled construction aluminium, and through his brother’s work, Martin Phiri attends his own funeral.

In the video, the same women in yellow and red T-shirts cry that same hopeless scream from my father’s funeral – and every funeral since the dawn of time. It is piercing and heart-wrenching. The exhibition of The Casket is unnerving. The wailing video plays above it and sends me back in time to my own father’s funeral. Body viewing is not enough. I expect a last word, a warm hand, a voice to reach me from the beyond – but all I see is musty skin, the same damp texture as tomatoes when they’re first taken out of the fridge.

It is not real. A man is more than his final resting place. A man is his ideas, his passions, his beliefs, and his actions – while his hands can still create. A man is made up of the things that live on – his words, his vision. The Casket terrifies me. Death is afoot, trotting toward me with fire, and I am leaving nothing behind. I run downstairs – away from the exhibition, away from myself, away from all thoughts of my father.

This is not real.

Martin Abasi Phiri is dead.