“Wildlife and nature are incredibly resilient and can bounce back if given the chance. Let’s give them that chance.”

_Thandiwe Mweetwa, Project Manager Luangwa Valley Team, ZCP

It is generally easier to be a pessimist, especially in conservation. For every statistic or published article regarding wildlife and nature that presents hope or optimism, there exist several that argue against it. The media tends to script our thinking and opinions, impacting our motivation, commitment to action, and most importantly, hope. This is a problem we seldom think about.

My article highlights a success story, something we are in dire need of, especially given the past few years’ events. The global impact of the pandemic, the colossal natural disasters, and the mysterious deaths of elephants in Botswana resonate in some way or form with our treatment of the natural world.

The country is Zambia, the region is the Luangwa Valley, and the species is the African wild dog or the painted wolf. The wild dog is one of the most underappreciated and misunderstood species. Despite an overall downward trend in their population across Africa (as per IUCN Red List), the Luangwa Valley has seen an uptick. Why? It is certainly not by chance.

The African wild dog is considered one of the most endangered animals in the world, found in only a handful of African countries. According to the IUCN Red List, an estimated 6,600 wild dogs are remaining (or about 660 packs), and a presumed continued downward trend. Whilst they once roamed practically every country in Africa outside of the Sahara and Congo Basin, the species has been virtually eradicated from North and West Africa, with only about seven countries with viable populations in Southern and East Africa; Zambia is one of them.

The Luangwa region has seen the highest density of wild dogs in many years, boasting the highest population of wild dogs in Zambia – somewhere in the range of 250-350 individuals or about 25 packs, as per the latest estimates provided by the Zambian Carnivore Programme (ZCP).

There have been some recent success stories about reintroducing the species back into parks, such as Mozambique’s Gorongosa National Park in 2018 and, more recently, in Malawi’s Liwonde National Park and Majete Wildlife Reserve. Both places have seen some success; however, the results might need more time to be conclusive. In comparison, wild dogs were never wiped out in the Luangwa Valley or in other parks in Zambia. The wild dog population has grown, and their natural habitat has been successfully protected due to the collective efforts of increased resource protection in many of these areas resulting in a higher prey base and fewer snares.

This Zambian success story is fed by two key ingredients – a unique natural ecosystem and impact-driven local conservation efforts.

Impact on the Ground

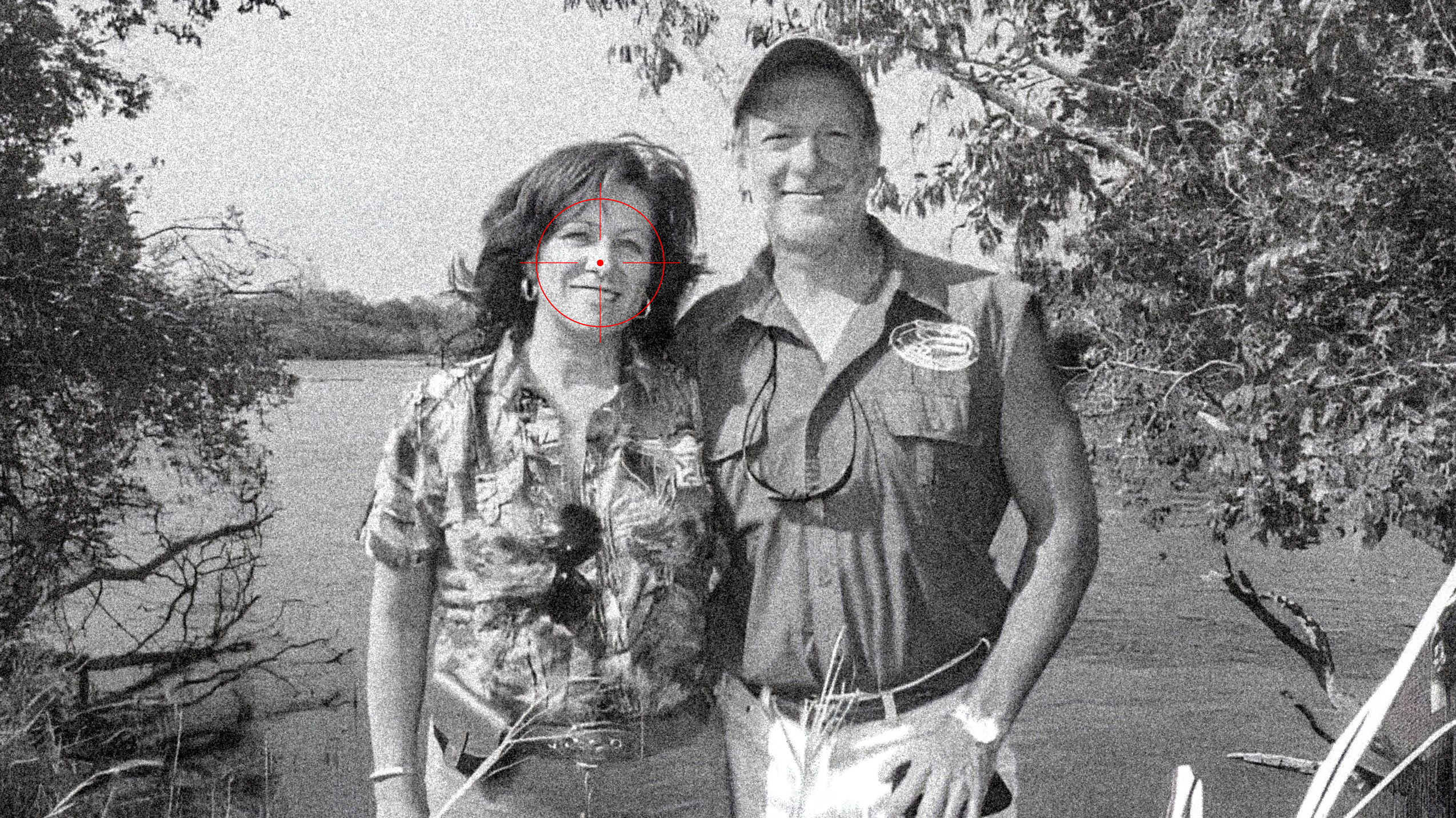

The Zambia Carnivore Programme (ZCP) team

Like many other national parks across Africa, the South Luangwa Valley faces its own set of challenges in conservation. Conservation efforts led by ZCP and Conservation South Luangwa (CSL), including support from Zambia’s Department of National Parks and Wildlife (DNPW), have paid attention to crucial issues affecting large species and have made an incredible impact over the years.

One of the biggest threats faced in the valley today is human-wildlife conflict, particularly bushmeat poaching – whether to feed the poachers’ families, contribute to the illegal bushmeat trade, or simply eradicate the threat of animals destroying crops or killing livestock. Bushmeat poaching is primarily undertaken through snaring and is a key focus for ZCP, CSL, and DNPW. Snares are specific tools that poachers use to capture animals, typically set up as a noose from wire or cable; simple and cheap but very effective. It is one of the cruelest and most destructive poaching methods, as animals can languish for days or weeks before dying. While some animals escape, their chances of survival are low due to infection or starvation brought by the lack of mobility.

A ZCP team member holds part of a poacher’s snare

The COVID-19 pandemic strained resources, but the teams were quick to adapt, effectively collaborating with partners and donors and thus mitigating much of the snaring impact. In 2020, the local teams provided anti-snaring protection to four wild dog dens, amongst other predators such as hyenas and lions.

Collaring predators contribute to assisting in the conflict that exists with local communities. As the animal movements are closely monitored, local communities and herders can be notified if there is a pride in the area to avoid contact. It also helps to keep the predators from straying too far into areas where they would threaten livestock or humans. This is especially true in unfenced and vast national parks like the South Luangwa National Park.

Alongside this initiative is tackling one root cause of the problem – education. Yet again, the efforts in this area are impressive; from community game drives and clean sweeps to school programs and support of degrees in wildlife conservation, it is evident that educating and training the next generation is as important as active fieldwork. There has been tremendous support from the surrounding local communities to preserve and protect the wildlife – this alone is an achievement and a future of hope and action. This also indicates that coexistence between humans and wildlife is possible.

A Unique Natural Ecosystem

Zambia has massive landscapes with much of the land untouched, which puts it in a unique position. Unlike many other well-known national parks and reserves in Africa, Zambian national parks are not fenced and hence have no issues with migration, thereby providing biodiversity ample opportunity to prosper. This inherently provides some protection for wild dogs in terms of range, terrain, and prey. Species such as wild dogs are rare by nature and part of their evolution. Their lifestyle is such that they move massive distances and hence require a great deal of space. Under these conditions, only the largest unfenced reserves can provide any level of protection for these species.

Between the Luangwa Valley and Lower Zambezi, the land stretches over 1,000 kilometers, of which animals are free to roam throughout this area. Combined in size, South and North Luangwa are estimated to be almost 15,000km2 – in comparison, the famous Masai Mara is only a tenth of this size, at 1,510km2. According to Protected Planet, Zambia has the second highest terrestrial protected area after the Republic of Congo, at around 40% and much higher than the 17% target set by the UN Environment Programme.

Alongside the continued conservation efforts, the ecosystem can continue to prosper. Zambia as a country is far from being perfect; political interferences, corporate interests in mining in the parks and hunting permits that the government still allows are examples of constant threats to the terrestrial protected areas. As human populations rise around reserve borders, the risks to wild dogs venturing outside are also likely to increase.

It is incredibly challenging to paint a black-and-white picture of progress, with the complexity of managing such a massive ecosystem and the everyday challenges from numerous stakeholders. Two steps forward, one step back. However, you look at this; it is progress. One day we will pull through this biodiversity crisis sooner than later. I will remain hopeful.

Check out more of Amish’s wildlife photography on Instagram: @chags.photography

Disclaimer: the photographer and co-author has not been commissioned to write this article on behalf of the conservation efforts. He has conducted his own research, which also includes spending time with the teams at ZCP and CSL, interviewing them and various third parties.

Photos and words by Amish Chhagan (Chags Photography)