My initial interest to photograph and identify the plants was sparked by the exposure to the array of beautiful species seen whilst we sauntered through the miles and miles of magnificent miombo woodland, exploring the Mutinondo area. Our guide, Paul Saili inspired us further by telling us the Bisa names, meanings and uses of the plants.

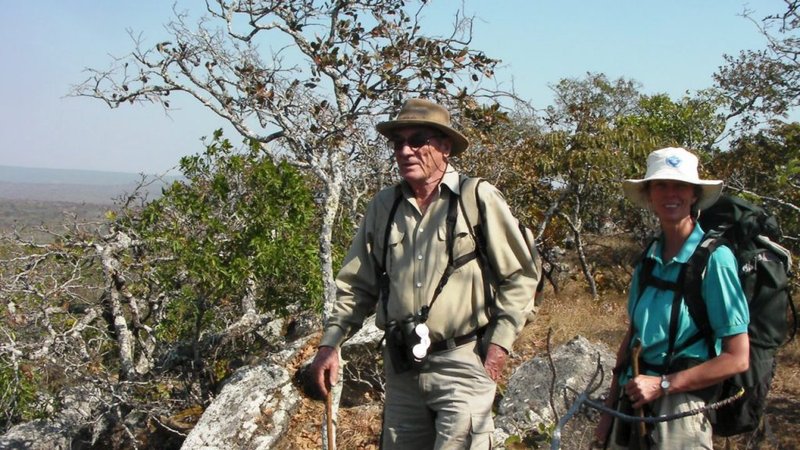

That was June 1994, when my husband Mike and I were looking for a suitable lodge site in an area between the Luangwa Valley and the Great North Road, 100 kilometres south of Mpika and 600 kilometres north of Lusaka, to create what is now known as the Mutinondo Wilderness. Mike was a retired agriculturalist, I was still practising as a jeweler and gemologist. Mike’s experience of wild plants was a working life of seeing and controlling them as weeds and since gemologists are supposed to spend their professional life looking at gemstones, just calling them “beautiful, nothing much changed for me dealing with flowers. We needed all the help we could get! The botanists at Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew (RBGK) must have heard our cry from the wilderness.

After an unsuccessful hunt within the local forestry departments for literature to translate the Bisa names into scientific ones, Gerald Pope, the Krukoff Curator of African Botany at RBGK very kindly sent us relevant checklists which were a great start in the identification process.

Local, common and scientific names often tell you much about the plant. For example, the snack bought along the roadside called “Livingstone’s fingers/potatoes” or umumbuchonde, meaning “yam of the bush” in Bisa, the scientific specific name esculentus is Latin for tasty, good to eat, edible. The first scientific record of the much enjoyed wild fruit masuku (Uapaca kirkiana) was collected by the early anti-slave trade activist John Kirk in present-day Malawi in 1862, during one of David Livingstone’s expeditions. (Masuku is also known as musuku.)

Scientific names consist of a genus and species (sometimes followed by the variety or subspecies) which can look intimidating until broken down into parts and meanings. Consider for example the Psorospermum febrifugum, a flowering plant species found in Southern Africa. Psoro means itch (the implication being that it alleviates rashes and psoriasis), sperm means seed and febrifugum means fever dispelling. It is also commonly known as the African Holly or umutombolia, which is a general term for “fruit” in Bisa. Erythrocephalum longifolium, is a stunning red daisy. Erythro means red and cephalum is head, longifoium means with long leaves (folia), the common.

The challenge to match plants to names on a database was launched when we bought our first digital camera in 2002. After seeing the accumulation of photos, Paul Smith from the RBG Millennium Seed Bank suggested that instead of a database, I should write a field guide. That was in 2008. Paul then got the ball rolling in getting the Mutinondo plants identified by distributing CDs of the database photos to the appropriate specialists at RBG, Kew. The African Dry Lands team at the RBGK did brilliantly (especially considering the quality of the photos). Paul provided much-needed encouragement and guidance. Along with Jonathan Timberlake, he sourced a copy of Flora Zambesiaca, which was the resource from which this field guide was written. Flora Zamesiaca is a manual containing a record of the plant species of the Zambezi River basin. Various other botanists from local and international institutes visited the Mutinondo Wilderness over the years, all generously and patiently helping with trying to solve the plant photos in the “ZZZ unknown” file.

These included several visits by Sally Bidgood and Kaj Vollesen from RBGK. Without Kaj and Sally’s incredible collecting skills and the hours that Kaj spent determining the specimens at RBGK, this book would have been half the size and half the quality. Kaj’s sharp botanical scrutiny as co-author raised the quality of the content considerably.

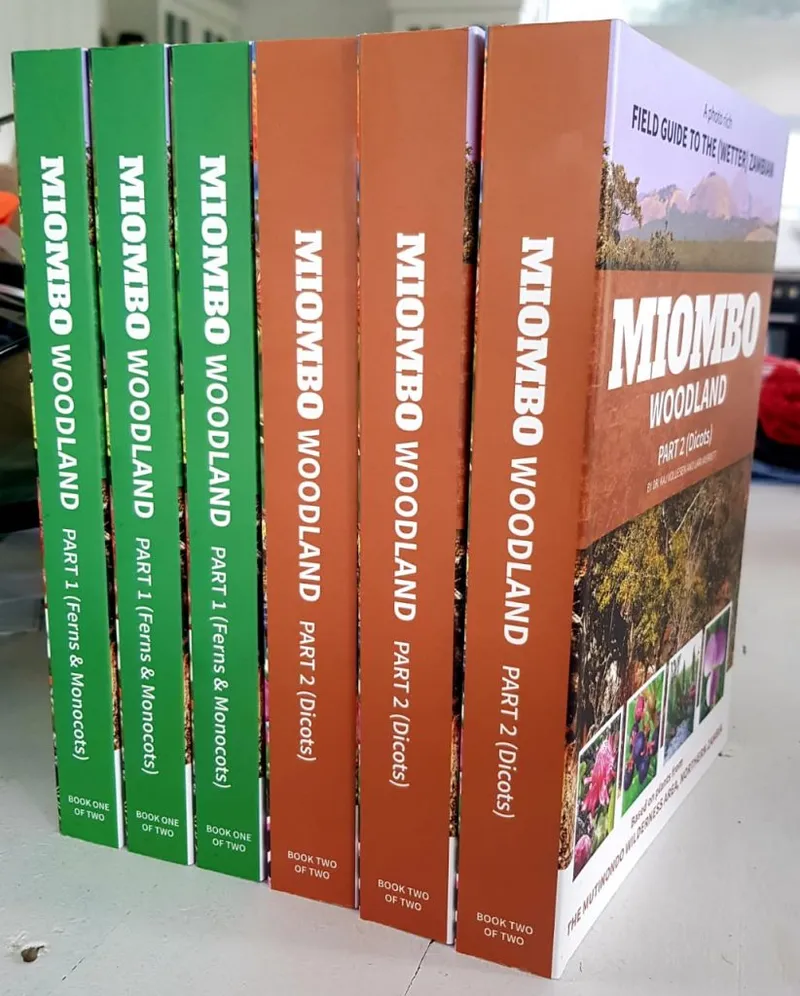

The above work resulted in identifying 1,634 species of which are 5 newly described or shortly to be described species, 19 possibly other new species, and 24 species are new records for Zambia. Since the book was completed we have found another 70!

Inspirations to actually finish the book came from three people who had put massive time and energy into writing books about the flora of Zambia, but never finished them; and three others: a former Zimbabwean Biology teacher, now working at RBGK, pushed me to not delay finishing it in the quest to try to make it complete; another was a butterfly collector who used the example of a very early and amateurish book on butterflies of Africa which was a vital stepping stone to all future work on butterflies in Africa (unlike the poor moths which have been left far behind); and thirdly, an author of an array of botanical related books told me if you want to learn about something – write a book about it!

May this book be a solid foundation for future research, appreciation and protection of the Zambian miombo for many future generations.

Larr Merrett is co-author of Field Guide to the (Wetter) Zambian Miombo Woodland available from Bookworld Zambia, Mike Parks Books and NHBS and Silverhills Seeds & Books and various websites. Lari is pictured (opposite page) with her husband Mike.