Zambian funerals embody deep cultural traditions, revealing how Zambian communities process grief through storytelling, ritual, and communal support. This article explores the symbolic nature of mourning, linking it to the broader context of African art—which is often misunderstood when viewed through Western perspectives.

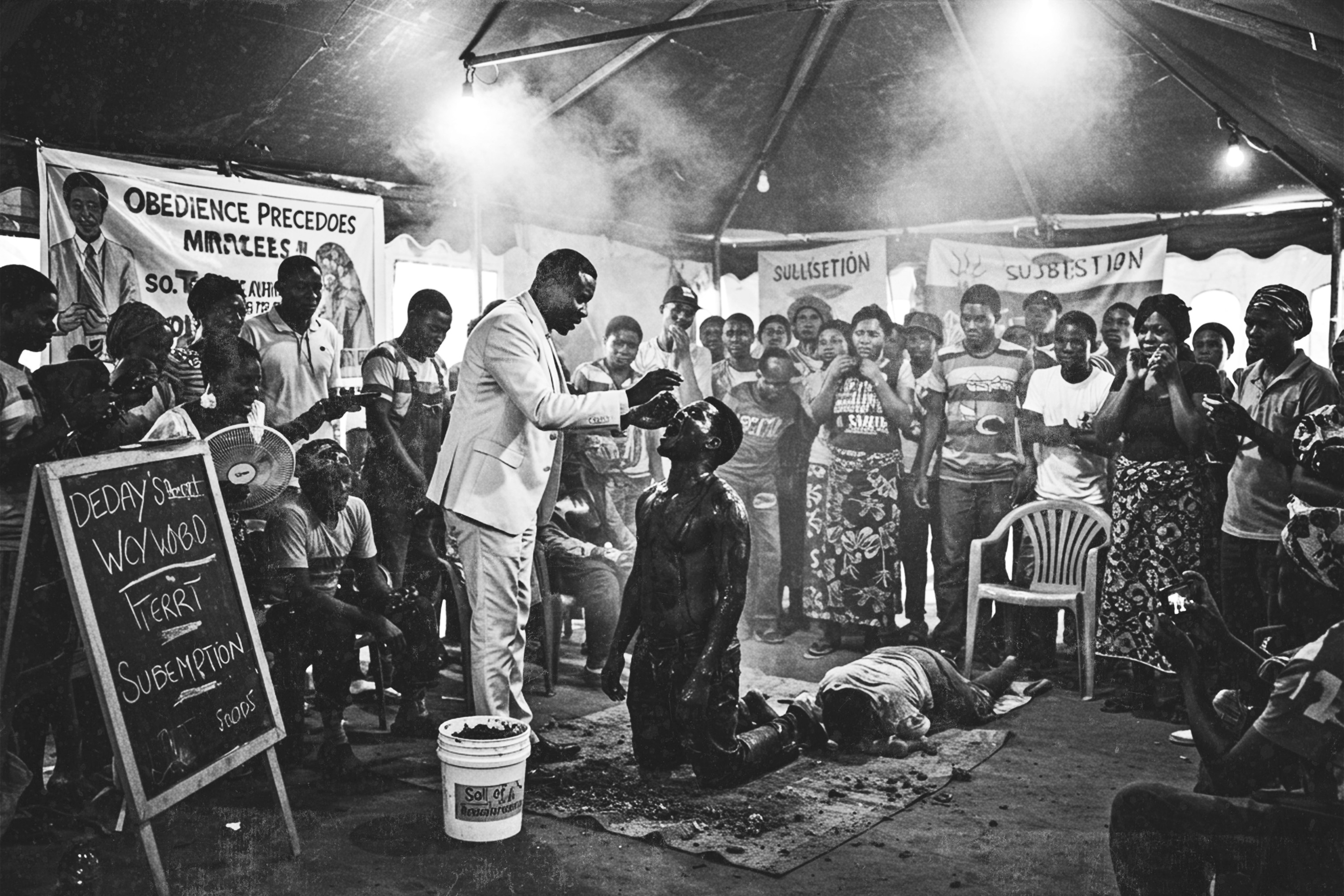

Culture is a fishbowl; anyone can look through it, but only those inside can truly understand it. A Zambian funeral is a perfect example. Nobody explains the need for the tent – typically army green – or why the furniture is carried from the living room to the outside, where the men will sit and raise a wood fire. The women line the living room floor, and the bereaved takes her reserved place in the corner. The television disappears, and there is always a choir. Mourners collapse into the house, now known as the funeral home, wailing—sometimes with dry eyes, sometimes with tears—beckoning to the departed now on the other side. Their dirges are devastating and bizarre, drawing every dry eye to tears. The loud cries prick the bulge of grief sitting heavy in the room.

When the mourners cling to the bereaved, they make sure to ask what happened. This part is important. The story has to be retold continuously. Each retelling exposes a new detail and shines a new light on old memories, unearthing the roots of grief and building a foundation for healing. On the last day, the mourners rise from the floor and bathe. At the burial ground, they touch the red earth and lay a wreath before returning to the funeral home to crown the ceremony with a meal and fresh, fragile laughter.

This is a Zambian funeral, known and understood in its context. Because we get it, human resource policies have loosened to accommodate the definitions of family and the ways of Zambian grief and mourning.

Defining African Art

Initially, I intended to present a neutral discussion on preserving Traditional African art. Many wise, well-researched academic documents support arguments for and against the cultural appropriation of Traditional African Art for the good of humanity.

My intentions were thwarted as I explored the material.

I am a Zambian woman with a Bantu lineage. There is no way to be neutral in this discussion–the best I can be is honest. With full disclosure and the utmost respect, I admit that there is a cultural fishbowl in the debate on African Art, and I am inside it.

Taking my lead from the editor, I spoke with the Director of the Livingstone National Museum, Victoria Phiri Chitungu. We must establish what things mean, and our discussion on the cultural appropriation of African art by Western artists and institutions would only be fruitful once in accord with African identity and the definition of art.

“Art is the product of a creative process intertwined with its creator. In a sense, art makes us human.” Victoria is a cultural historian, a student of life, a teacher, and a custodian. In an objective, quick-paced conversation, she schooled me on the confines of art and who it belongs to.

African Art: Beautiful and Misunderstood

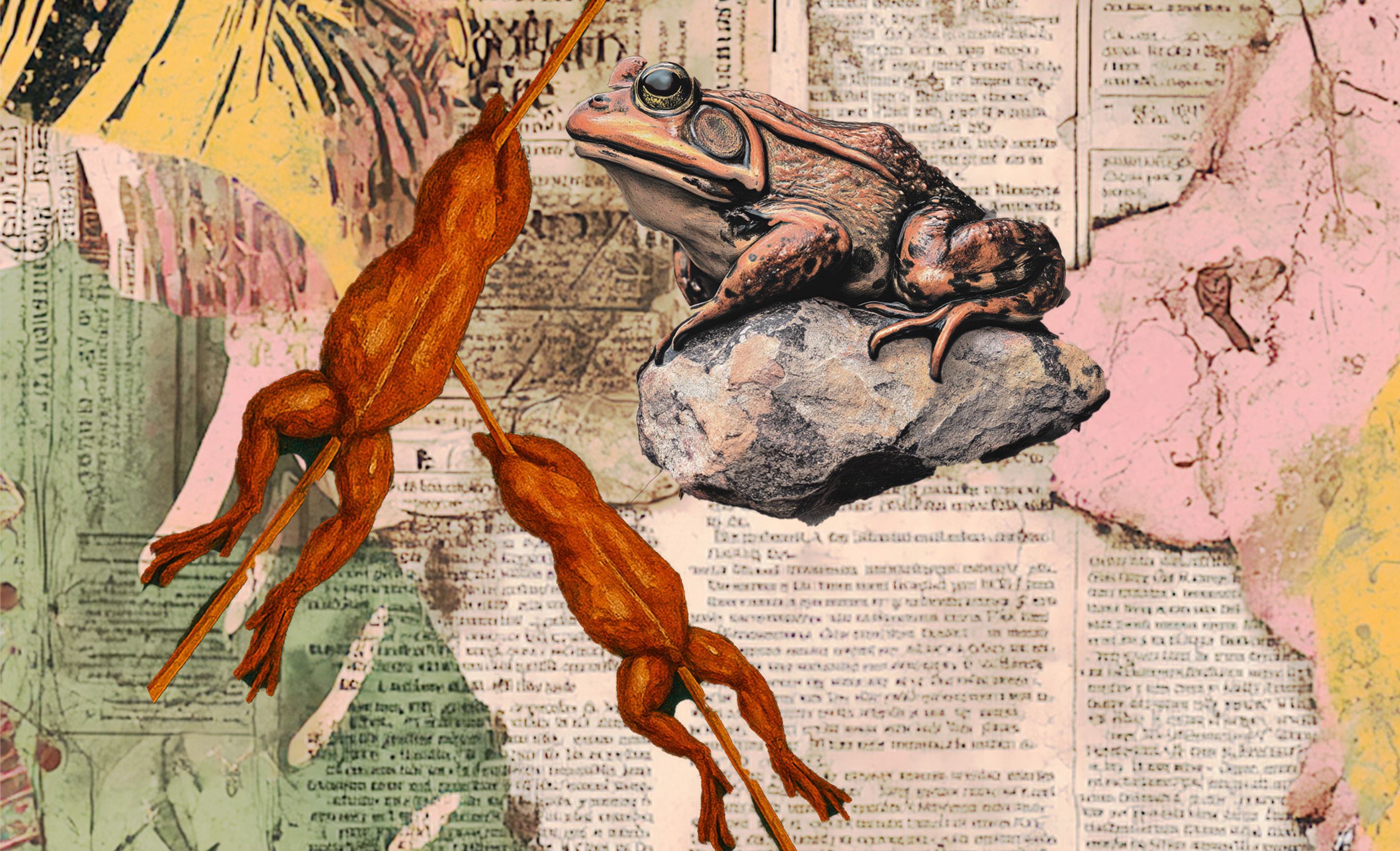

African art defies and transcends Western definitions. The narrow concept of fine art limits it to a collectable artefact—made for beauty, self-expression, or aesthetic admiration. This limited perspective has led to the misunderstanding of African art. African art is made with a purpose in mind – whether for ritual, functionality, or cultural expression—and its purpose, beauty, and self-expression are not mutually exclusive. African art is alive.

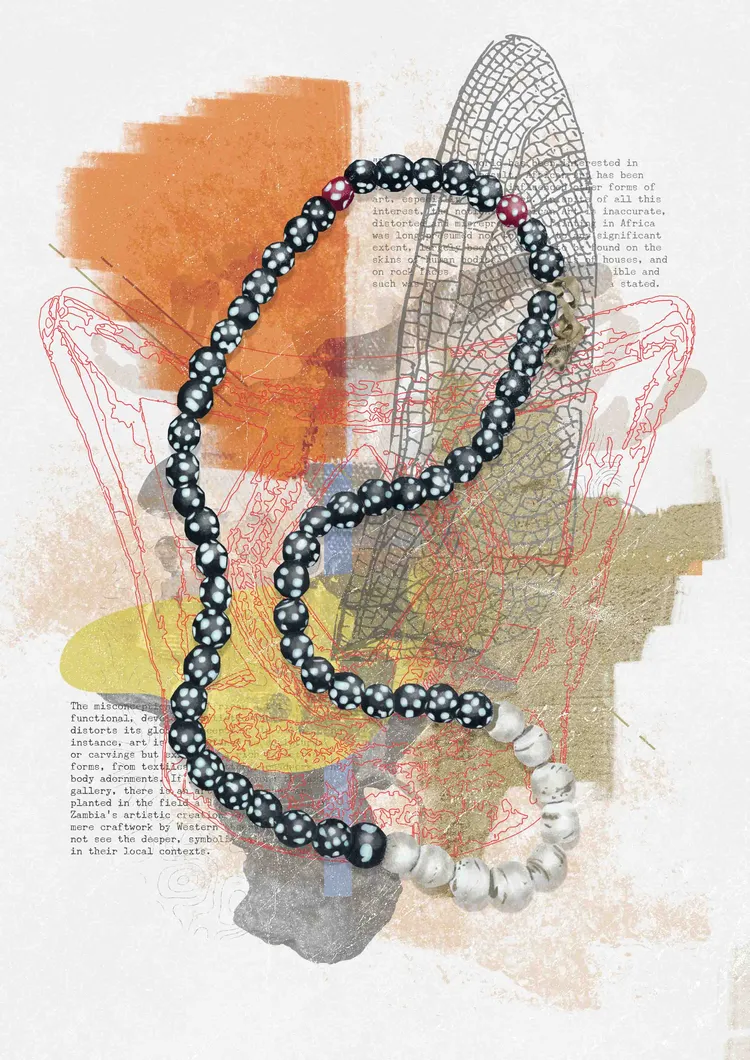

The misconception that African art is purely functional and devoid of artistic merit further distorts its global appreciation. In Zambia, for instance, art is not confined to sculptures or carvings but exists in a rich variety of forms, from textiles to pottery, beadwork, and body adornments. If you look beyond the art gallery, there is an art to how crops are planted in the field and preserved. Many of Zambia’s artistic creations were dismissed as mere craftwork by Western observers who could not see the more profound, symbolic value they held in their local contexts.

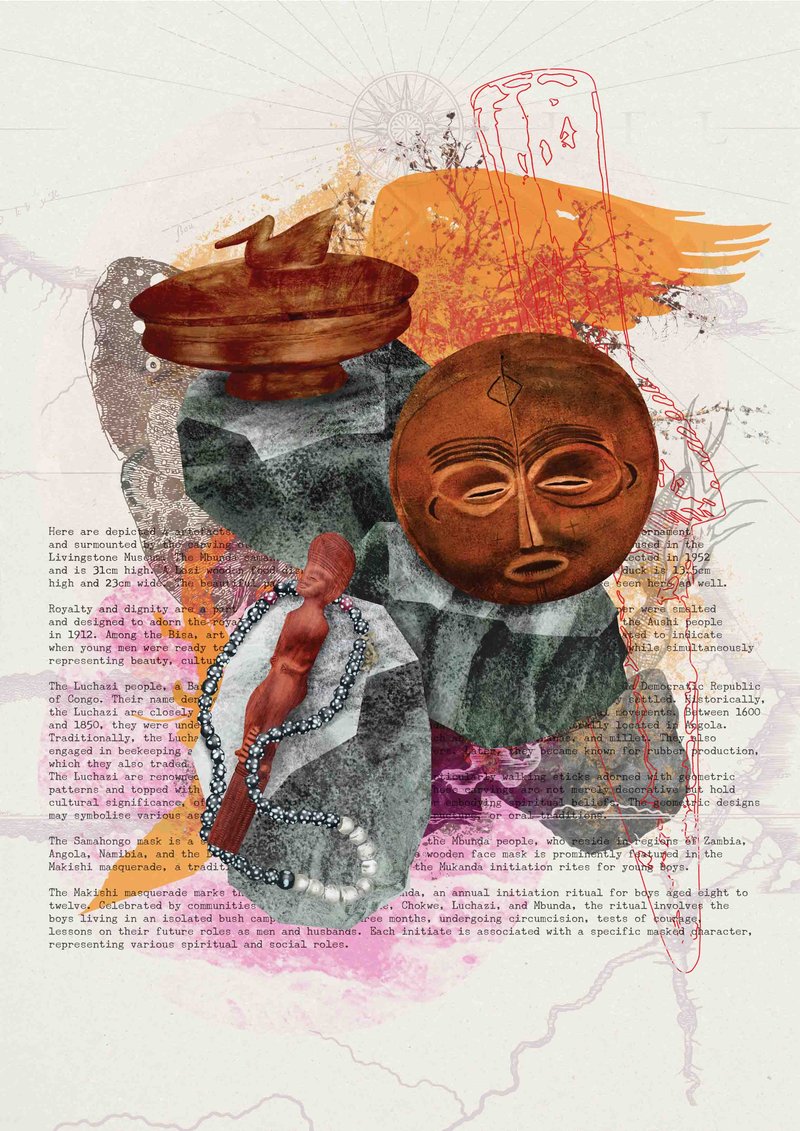

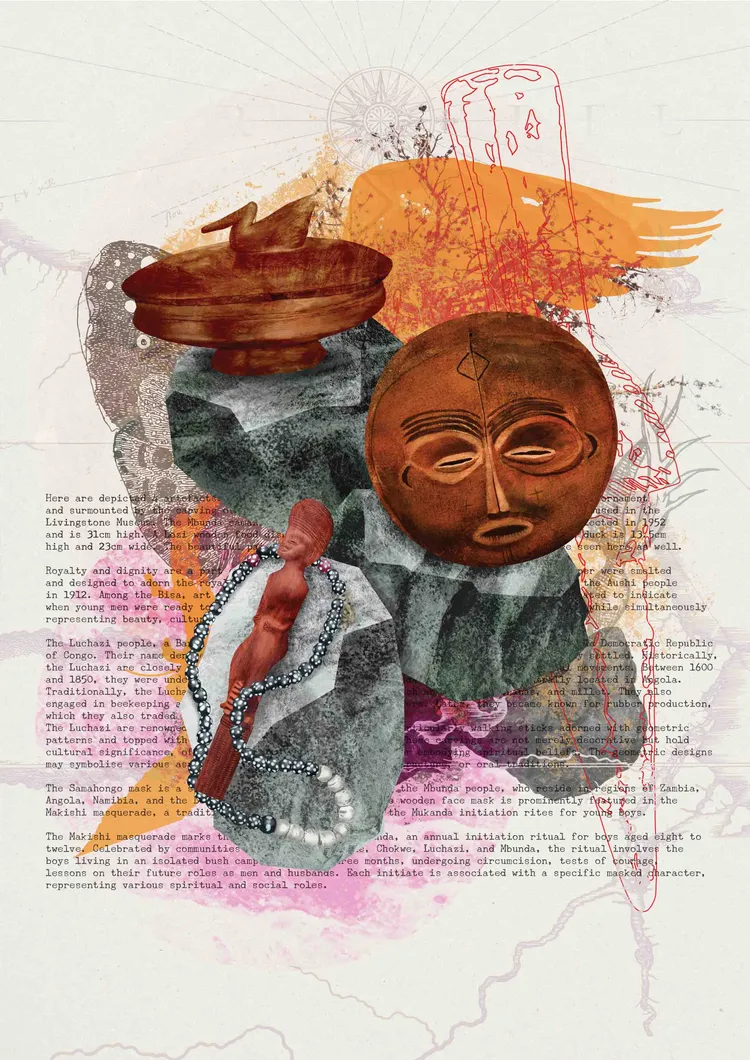

Traditional Zambian art, in all its forms, is a way of life, a means of communication, a preservation of heritage, and a celebration of the environment. In the smooth animal-skin skirt from the Valley of the BaTonga, you will find a story of love and dedication in how the skin is refined and lovingly beaded. Royalty and dignity are a part of African culture, and there is an art to how gold and copper were smelted and designed to adorn the royals and high-status people who wore the Mpande Necklace among the Aushi people in 1912. Among the Bisa, art carried a message – belts, finger rings, and earrings were created to indicate when young men were ready to join society and marry. Each piece served a practical function while simultaneously representing beauty, culture, and history.

“For decades, the world has been interested in African art. As a result, African art has been widely studied and influenced other art forms, especially Western art. Despite all this interest, the notion of African art is inaccurate, distorted, and misrepresented. It was long presumed that ‘painting,’ as it relates to ‘painting’ in the West, did not exist in Africa to any significant extent, largely because it was to be found on the skins of human bodies for tribes like Tonga, on the walls of houses for the Bemba, and rock faces—none of which were collectable and, as such, could not be considered as ‘art,’” Victoria stated.

A closer inspection of history leads to the discovery of the Mwela Rock Paintings, among the oldest rock art collections in Southern Africa, estimated to be between 2,000 and 8,000 years old. The Mwela Rock Paintings offer valuable insights into the social, spiritual, and artistic practices of prehistoric communities in Zambia. In the Kalambo River Gorge, evidence of stone tools, fossils, and artwork stands as proof of art that transcends function and blends into the formation of identity.

Victoria shared that art, at its core, is the product of the creative process. It is inseparable from its creator and reflects a deep bond between the artist and their environment. In Zambia, as in most of Africa, art mirrors the daily life of its people, capturing the interplay between tradition, belief, and creativity. It is a testament to who we are and where we come from.

“African art is vast, and each region has its own style. It is often assumed that the African artist is constrained by tradition, contrasting with the ‘freedom’ given to the Western artist. But traditional African art equally demands high levels of inventiveness, encouraging creativity, visual abstraction, and conventionalisation; a visual combination of balanced composition, asymmetry, and a general multiplicity of meaning,” she explained.

The Commodification of African Art

Zambian art is not the star of African art history. It is often overshadowed by the more widely recognised art of West Africa and the Congo. This misplacement is partly due to the dominance of other African traditions in the global art market, whereas art forms from Southern and Eastern Africa have been vastly underappreciated. While Zambia has a wealth of artistic expression, the international gaze has historically failed to identify and celebrate its unique contributions to the broader African art scene. Well-known African art was first taken from its source, popularised, and then culturally appropriated in ways that do not respect, acknowledge, or benefit the source.

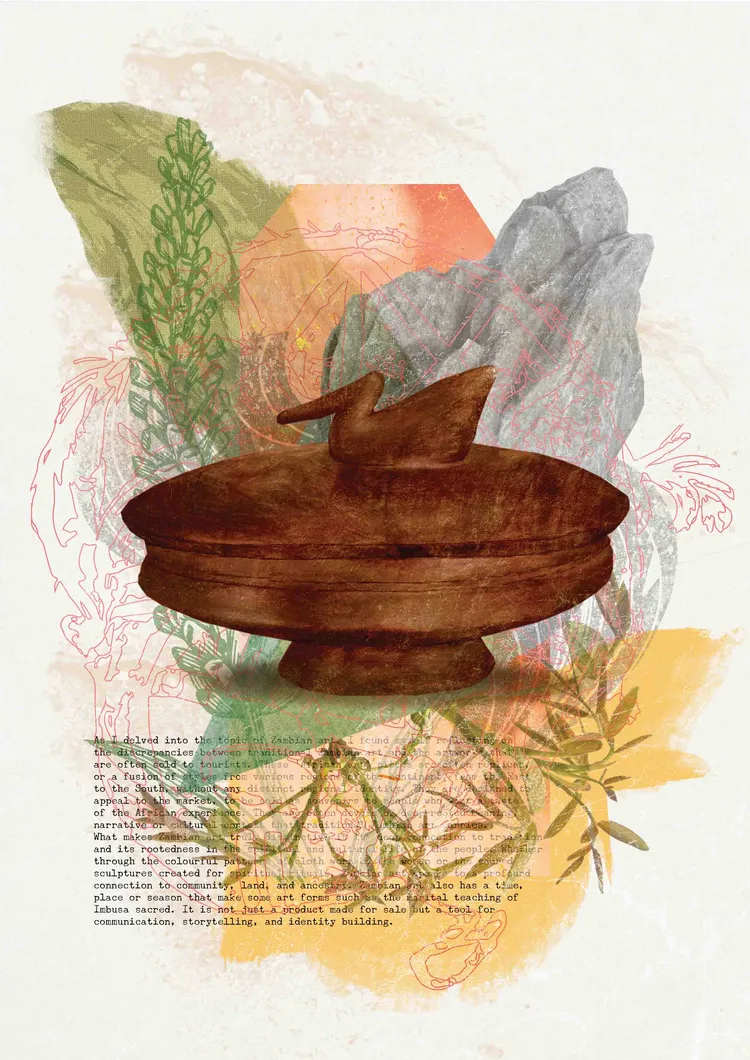

As I delved further into Zambian art, I reflected on the discrepancies between traditional Zambian art and the artworks often sold to tourists. These ‘Zambian art’pieces are often replicas or a fusion of styles from various regions of the continent, from the East to the South, without any distinct regional identity. They are designed to appeal to the market and be sold as souvenirs and commodities to people who want to taste the ‘African experience.’ They often lack the deep-rooted meaning, narrative, or cultural context that traditional Zambian art carries.

What makes Zambian art genuinely distinctive is its deep connection to tradition and its roots in the spiritual and cultural life of the people. Whether through the colourful patterns of cloth worn by the women or the sacred sculptures created for spiritual rituals, Zambian art speaks to a profound connection to community, land, and ancestry. Zambian art also has a time, place, or season during which it can be observed or interacted with.

Among the Bemba people, the Chimbusa—a transitional initiation ceremony before marriage—painting is intrinsic to the process, serving a spiritual and pedagogical role. The red, black, and white colour codes of the ceremony are painted onto the body and the walls of the hut where the ceremony is conducted in geometric designs, patterns, diagrams, and motifs that represent fertility, beauty, and protection and tell the story of the transition from childhood to adulthood. The secrets of the ceremony are passed down from one woman to another and thus cannot be displayed in a gallery.

Unlike the fragmented, commodified art forms often seen in the global market, traditional Zambian art is an active, living expression of culture. Here, we see that African art is not just a product made for sale but a tool for communication, storytelling, and identity building.

As Victoria and I continued our discussion, it became clear that this art cannot simply be taken from its context and placed on a shelf to be admired as an object. It is an ongoing practice tied to an inherently African way of life. The Zambian artist is not constrained by tradition but rather inspired by it to innovate and create. The best portrayal of this is the artist and creative prodigy Ignatius Sampa, whose life, work, and death fed the lore of Makishi. His depiction of Makishi caricatures fused the bedrock of Western and Zambian art to shed new light and provoke a deeper inquiry into both art forms.

A New Narrative for Zambian Art

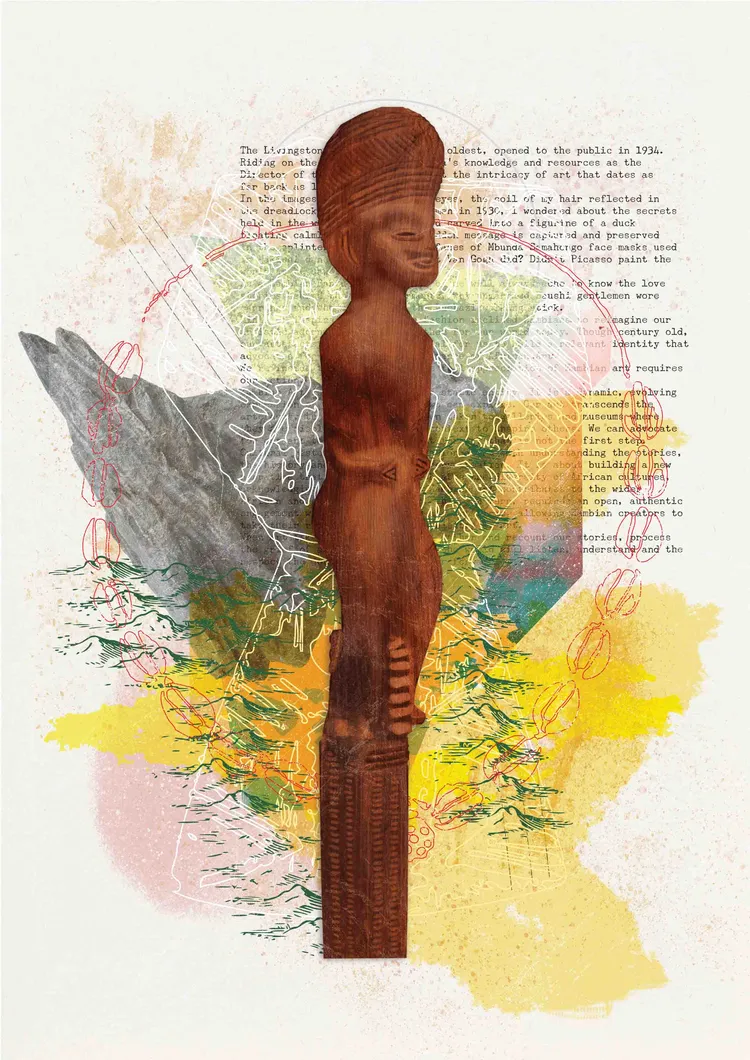

The Livingstone Museum, Zambia’s oldest, opened to the public in 1934. Riding on the abundance of Victoria’s knowledge and resources as the Director of the Museum, I gasped at the intricacy of art that dates as far back as 1912.

In the images, I saw my nose, my eyes, and the coil of my hair reflected in the dreadlocks of young Luvale women in 1930. I wondered about the secrets held in the wooden dish with a lid carved into a duck figurine floating calmly above water. A hidden message is captured and preserved in the splintered, expressionless faces of Mbunda Samahongo face masks used in Makishi dances. Isn’t this what Van Gogh did? Didn’t Picasso paint the world as he saw it?

As a Zambian Bantu woman, a part of me will always ache to know the story behind the art.

Hints of inspiration exist for fashion-inclined Zambians to reimagine our artistic adornments and create them for our world today. Though centuries old, our artefacts are full of potential for us to build a relevant identity that advocates for the value and importance of African art. We’re inside the fishbowl, and the full appreciation of Zambian art requires our action.

Zambian art is not an isolated or static entity. It is a dynamic, evolving expression of culture that only we can explore. Our art transcends the artefacts—these have been taken to galleries and museums, where they are displayed with minimal context to inspire others. We can advocate for our art to return home, but that is not the first step for me.

Cultural restoration and preservation start with understanding the stories, the history, and the meaning behind every creation. It is about building a new narrative that respects and celebrates the diversity of African cultures, acknowledging the richness that Zambian art contributes to the broader African and global conversation. This, in turn, requires an open, authentic engagement with the culture and its art forms, allowing Zambian creators to take their rightful place in the history of art.

When art takes its place, we will gather and recount our stories and process the grief of all we have lost, and the world will listen, understand, and respect the journey we must chart forward.