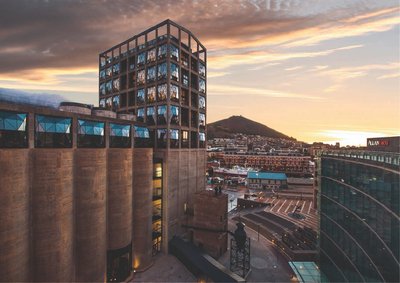

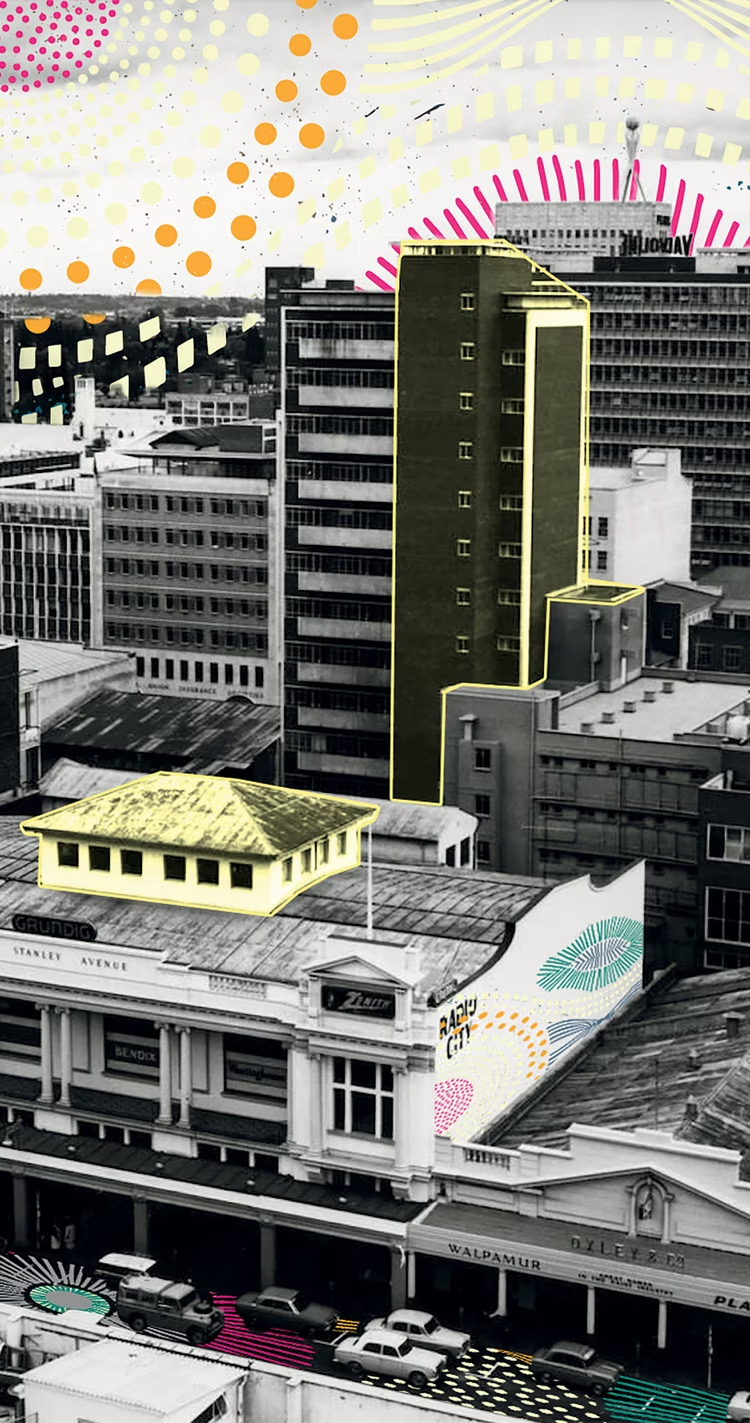

It is a sobering reality to comprehend that the economic value and scarce resources that we seek in Lusaka are outside of it.

Trapped in a bubble that only allows us to explore the parts of Zambia packaged for a first-time visitor to the country, Lusaka sometimes prevents us from moving away from the oft-beaten track, with hardly any curiosity about what lies beyond the vision of our mental Lusaka map.

On a recent trip to the countryside, after a ten-year hiatus of my own, I discovered that a barren and unproductive landscape is far from the truth of our villages. It seems everyone else, except the owners of the said land, seemed to have migrated to the rural areas and set up camp for one entrepreneurial venture or another. Our destination was 1,227 kilometres from Lusaka, far up in the north-west in a place called Chavuma. Most people are familiar with Solwezi and perhaps Mwinilunga because of the mines, but our destination was past these towns, another 600 kilometres or so. The traffic was thin, and the road was newly built. The only indication of activity was the occasional loaded trailer truck that we crossed. We passed through Kasempa, Mufumbwe, stopped in Kabompo for a couple of nights and travelled on to Zambezi and finally got to Chavuma.

The area was remote, far from what my mind remembered, but certainly not desolate. The trucks we saw laden with burdens were in fact loaded with thick rosewood timber logs being harvested deep in the rich Miombo woodland of Kabompo, Zambezi North and Chavuma North. We also passed an enclosed camp with high-end-looking trailers in what seemed like the middle of nowhere, between the towns we passed. There was significant evidence of various endeavours in the area, but it was not by the locals. The locals knew what was happening and, on some occasions, participated in it, but they were not in the driving seat of this activity. You had to ask the question why.

Kasempa, Kabompo, Zambezi and Chavuma have some of the richest Miombo woodland that yields 80-100 year old mukwa, rosewood and mukula, one of the most highly sought out timbers at the moment. Kabompo also has some of the best honey in the world, and traders come to buy from the locals for export. It has been reported that Zambia could be Africa’s second-largest producer of honey after Ethiopia if the right investment were made in honey production. The region is home to the Zambezi, Kabompo and many other rivers, water bodies and tributaries that are rich in marine life, which, according to the locals, most of the community has not economically exploited because they don’t know how to scale it up. The mining prospects in the region are a given. Livestock, farming and tourism potential are just a few more I could add to the list. The little-known West Lunga National Park in Mufumbwe has been neglected, but it still has immense wildlife and safari offerings.

Interestingly enough, in one of the council offices that we visited I read through a decentralisation document published by the government that expounded policies of development, community inclusion, infrastructure development, local manufacturing opportunities, sector development and investment but obviously the reality is entirely different. The rhetoric is strong, the stage dressing is exquisite but somehow, we are missing the show.

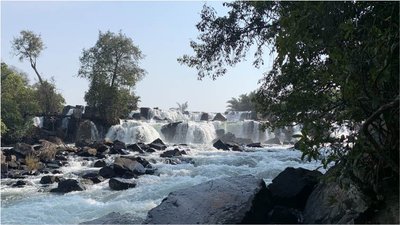

The show we enjoyed, nevertheless, was the magnificent landscape that kept on revealing itself in subtle but full force. Proving the point of the unexploited tourism potential in the region. The first discovery was the Mutanda Falls, just a few kilometres out of Solwezi. It sits on a small private property but is visited by the locals in the know. The chalets are situated right at the mouth of the cascading waters, and the rushing roar soothes you into a lull that only nature can produce. The morning mist envelopes the surroundings, adding to the pristine beauty of the natural feature.

The drive further north is through a canopy of Miombo woodland trees that happen to be shedding leaves and turning colour in full glory of nature’s magic. When we stood on the hill watching the sun rise from the bow bend in the Kabompo river, I envied the community lucky enough to wake up to this sight.

As we drove into Zambezi town, we followed the river of the same name as it snaked its way through the plains. A tarred road and modern brick houses lined the streets. We passed a bank, shops and a petrol station. We then drove down into the valley to see the wide river called “Yambejhi” by the locals, also where the name of the river is derived, with clear water and white sandy beaches that stretched for miles.

If you continued to follow the river, it would take you to Chavuma, our final destination, a town immediately below Angola, with only 11 kilometres between the district and the border town of the neighbouring country. The sandy beaches continue for several miles with rocky formations that create a waterfall that is at the centre of the community dwelling. In the late afternoon light, young boys can be found diving off the rock cliff into the water as the girls soak their fully-clothed bodies in the cool, clear water till the sun goes down. The river is the life force of the community, and the people exist in harmony with it.

The north-west revealed a little piece of paradise. Who wouldn’t want this? Riverfrontage housing, accessible waterbodies, vast skylines to view the rising and setting sun, thick woodland and land that is fertile, waiting for development and hardworking people. The people who leave Chavuma always come back because the territory provides for them what they need.

In North-Western Province, the symbiotic relationship with the land is still very tangible; the people take care of it, and it takes care of them. Being so far from Lusaka, most of the homesteads can be traced back several generations, with not much movement. Land has been passed on from generation to generation, and somehow it continues to give them a level of subsistence. It could be so much more.

Beyond the Copperbelt, it is hard to imagine anything farther than Solwezi (the new Copperbelt). You mostly expect to see a barren landscape and scattered mud huts, but this is far from the truth. Instead, you encounter beautiful scenery that is probably unknown to most but has generated interest from many who see the value and are coming in droves to claim it.

The stone-cold fact is that Lusaka takes us away from reclaiming significant parts of who we are and what we have to offer as a country. Other people have seen the value and are capitalising on it. It is an exploitation that does not necessarily favour the locals. It is a startling reality to come face to face with. This was our experience.

We have lost the connection to our lands because Lusaka obscures and hides from our heritage and entrepreneurial view, the wealth creation opportunities and lifestyle experience that could far surpass anything we crave in Lusaka. Our parents and grandparents left the village countryside to seek wealth in the newly liberated capitals, which was necessary for the time. What we need to do is go back and restore the imbalance that has been created from that absence. We need to reclaim the wealth and establish our position so we don’t lose the opportunity for growth, development and fortune.

There is an economic and cultural fracture between the countryside and the city that has caused an imbalance that needs to be restored, with Zambians driving the process. It is not just in Chavuma but every single rural district in Zambia that is just as well-endowed with human capital and resources. We owe it to ourselves.

Zambians need to go back and explore the economic potential of their homelands and find a way to protect the interests of the land for posterity and prosperity.

Will you go back and take ownership of the land and raise power structures, instead of sleeping in Lusaka? That is my question to you. To all of us.