We will write like us, in our voice, in our cadence, in our philosophy.

Ngu!

Ngu!

Ngu!

My mother makes music when she cooks: swift turns, tender swirls, gentle splashes, firm shakes, and precise cuts. Her cooking is alchemy. She grows a thriving garden on our land, where half is cultivated in neat rows, and the other half is wild. There’s always an element of surprise when she cooks; we never know what we will get.

From the warm thud of the pestle against the well-worn wooden mortar, I know when we’re getting ifisashi – a delicacy of food cooked in pounded groundnut paste. Why is this exciting? She pounds down the groundnuts herself as she has done my whole life. It is a special sound. She could use the food processor to blend down the nuts, and we would never know, but the process of pounding down the nuts to powder and knowing when to stop before they become paste is generational.

Contemporary Zambian identity is spread thinly across all the elements that form it. We have the influence of exposure from travel and multicultural alliances, corporate careers, industry, and trade, and the daily interaction with English as an official language. It is easy to forget that we are a Bantu nation of seventy-three ethnic tribes. Most Zambians are a blend of the tribes, myself included. My parents are Namwanga and Tonga. I have always felt fortunate to have the pedestrian knowledge of my ancestry but never felt the nudge to dive deeper.

On a rainy afternoon, Shammah, the Editor, gave me the nudge I needed. Armed with a few paragraphs in a synopsis and curiosity as a guide, I encountered the flow of life of the Tonga people. I accidentally unlocked why ifisashi is innately special to me.

I’ll shamefully admit that I don’t know enough about the Tonga people. All I know about the tribe has been observed from the bottom of my family tree looking up. It is said the name ‘Tonga’ means ‘independent’, which refers to the fact that before colonisation, the Tonga tribe was reported to have been a tribe without chiefs, unlike other tribes that surrounded them.

Zambia’s original Bantu inhabitants comprise at least 12% of the country today. The details of their exact origins are scarce, but historical markers have the Tonga people mentioned as hospitable and generous.

This text from Emil Holub about the Tonga, whom he mistakenly refers to as Toka near Victoria Falls, in 1885, caught my eye:

“The tobacco pipe plays a very important role in the life of the Matoka. … They have a surprising skill in making highly artistic tobacco pipes. The bowls of the pipes are made of burnt clay and have carved animal heads such as wild pigs, gnus, buffaloes, roan antelopes, water antelopes, oxen, goats, lions, etc. … The pipe is lit by coal. To handle the coal, the tribes use little fire tongs made by the Matotele. While they are smoking, all quarrels and strife are suspended, and when they invite strangers and unknown visitors to smoke with them, this is a sign of friendliness.”

The Tonga are predominantly identified by their homeland in the Southern Province, extending from the Gwembe Valley below the Zambezi River to Victoria Falls. The culture and history of the Tonga people are intricate and dynamic. Still, it would be dishonest to tell their story without noting the impacts of displacement, colonialism and development on the partial erasure of their history.

September 10, 1958, is a dark day in the history of the baTonga as it coincides with the displacement of more than 50,000 Tonga people from their homeland. The raising of the Kariba Hydroelectric Power Dam in 1957 birthed Lake Kariba and stood as the largest man-made dam in the world. The force of the god of the Zambezi was once so strong that its floodwaters caused an accident during construction, which claimed the lives of almost 90 people; 17 are still plastered on its walls today. Among them is my mother’s oldest brother, Austin Mwiinga, who has nobody alive to remember him. All we have left is his handsome face in a tiny square, sepia-toned photograph and his name engraved at the memorial epitaph. The most famous legend of the Tonga is that of the Nyami Nyami, the river god whose wrath broke the walls of the Kariba dam. But for all we know about him, I often wonder what other burial sites, shrines and ritual cultures were buried beneath his waters, never to be remembered again.

The Tonga people are a doing people. The oldest person in my family is an old lady, only known as Mukopekope. She has spent the last five decades blind from old age, weaving well-ropes and smoking her tombwe – her beloved tobacco pipe. As a little girl, I’d twirl around the long, winding ropes while she worked on them deep inside her hut. Retirement is often framed as a time to do nothing finally, but no matter the age, Tongas are always doing something, and Mukopekope still weaves her ropes today.

Community archive = (persons participating) [in] (storytelling) [using] picture elements on the internet

It was so special to find that carving, weaving, creating and doing are integral to life for the Tonga people. My journey into my ancestry led me to discover the points where my personal archive met the archive of the entire tribe. One such point of convergence is with artist Banji Chona, who, like me, is one part Tonga. Currently defining herself as a Zambezian, Banji is an artist, researcher, and curator with a deep immersion in the elements of Tonga’s history. Her artistic practice is devoted to using natural elements in creating offerings grounded in the telluric and spiritual practices of the Tonga people. Her identity as a Zambezian is an intentional questioning of identity, naming, meaning and tradition.

Banji generously shares that her first word was ‘Banininini‘ – a Tonga word that means very small.

She describes Tonga as the language of her heart while detailing her interactions with Tonga as a language. As an academic, English is the language of research, findings and presenting arguments and discoveries. This is seen through Banji’s reflective presentations in Ngoma Zya Budima.

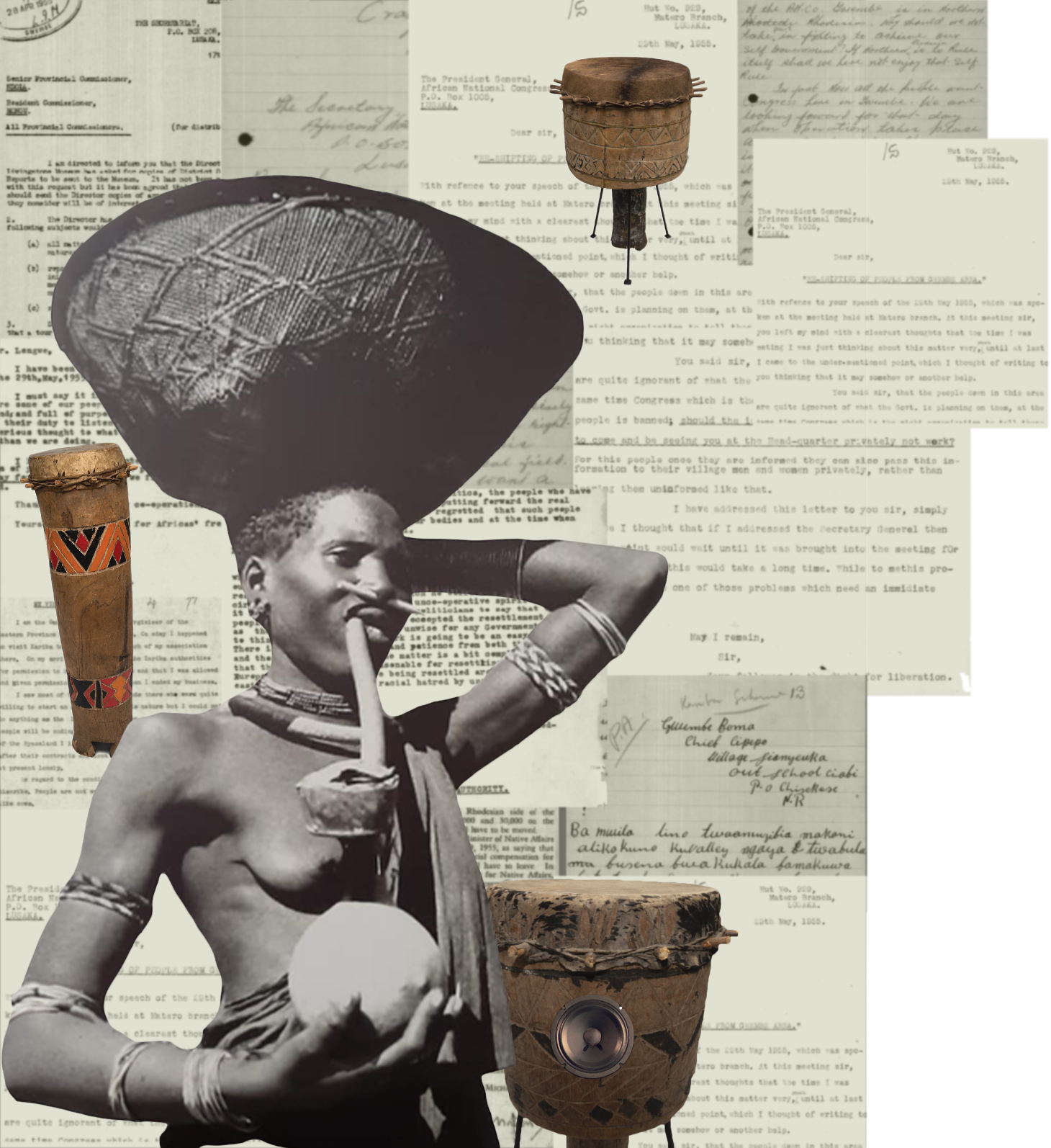

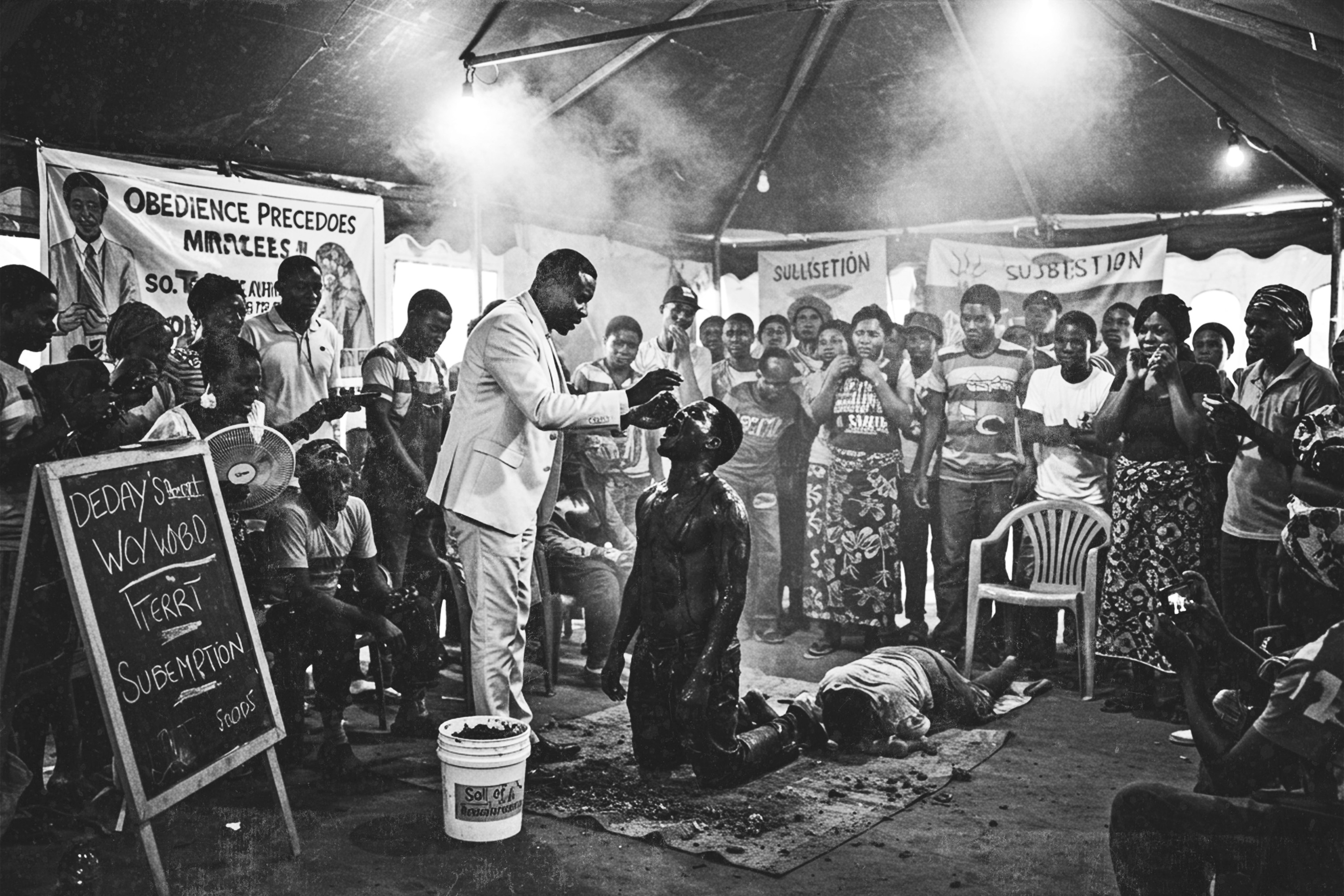

Ngoma Zya Budima is an intimate research catalogue born from the exploration of grief following the loss of her grandmother. The multi-medium body of work is a product of the research conducted and employed in collaboration with The Women’s History Museum and The Swedish Ethnographic Museum. The work aims to give indigenous object owners agency in the research and archiving process that provides room for narratives and complex identities. In Ngoma Zya Budima, we encounter the Drums of Darkness and natural objects created for the dead during periods of mourning. I have seen the role of musila, soil from the grave applied to the faces of the mourning family, and kunyola, which is the shaving of heads during a funeral, in my family. Still, seeing it extrapolated in Banji’s work gave these rituals the depth and meaning that were lost on me but which my family innately understood but had no words to explain.

Radical Zambezian Archvie

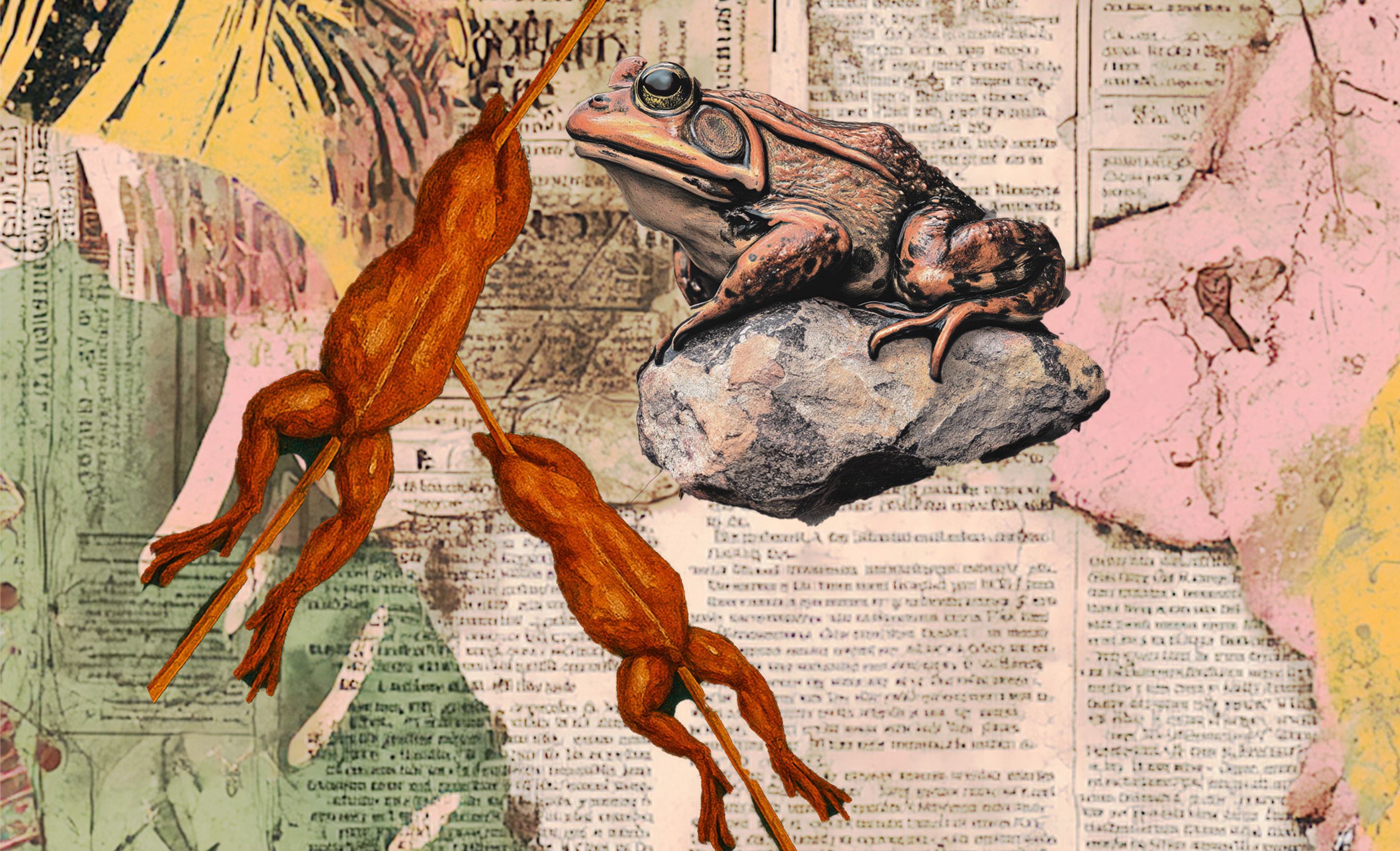

In her work, Banji employs everyday objects that have meaning to her to express the hybrid conditions of life, then and now. Her works comment on the absence of context in ethnographic images by overlaying her context onto the images. Digital collages transform images lacking context using the symbolism of a blue moon butterfly to communicate grief and the powerful impact of subwoofers. This helps us understand how the world of sound, in this case, Ngoma Zya Budima, can leave marks on the physical world.

The project gets its name from the Tonga drums used for thanksgiving and expressing sorrow. The drum’s hollow body, moving air, and making sound act as a speaker. The skin on its surface reacts to the air, temperature, and how strong it is. Hands and ears are like channels, both effectors and receptors of this auditory experience. Subwoofers speak to the auditory perception of oral narratives generated by personal and collective remembrance.

Disruption and Reclamation

Banji adds a new light to intimate practices through descriptions and image additions that complete the story. There are gaps in the context of the ethnographers’ photographs, but with insight and perspective, vital context is returned that brings them back to life. Reimagination and repatriation are forms of resistance. Now, I know and respect the practices I’ve observed my whole life and yearn for their return.

Banji’s reimaginings express community-led archiving that challenges established, ‘conventional’ methods of collecting, storing, and telling history. Ethnography often finds itself far removed and divorced from the origins, thus creating isolated objects or artefacts with assumed histories and incorrect contexts attached to them. In the case of funerary rites of baTonga, musila and kunyola are presented as romanticised portraits, seemingly acting as a catalogue of everyday life, when contradictorily, the imagery presents the sobriety of families in mourning.

Tonga history is shrouded in an inescapable mysticism. The indobondo is a finely carved water pipe that Tonga women have used to smoke tobacco for centuries. Logic tells us that tobacco is harmful, but there are claims that indobondo has immune benefits. However, through The Community, origin and meaning are re-attached. In present-day Tonga culture, significance and identity find a place in a process as simple as kutwa (pounding). Despite a history often distinguished by displacement, the braiding of rope, weaving patterns into cisuwo, and the striking of ngoma zya budima all act as visual and auditory cultural cues. Tonga culture reclaims its space in modern-day society through “acts of resistance” such as smoking incelwa or indobondo and adorning the neck, arms, ears, and nose with bulungu, ikaya, kancolo and cisita. Through photoreception, Tonga identity and culture are upheld through the living archive.

The Archive

Family is the first school. We learn our first words, mannerisms, values, and the beliefs that eventually form our identity. When I hear my mother pounding groundnuts, I hear my people. The firm, consistent thud lulls me into relaxation and anticipation of the deliciousness to come. Today, I know about the macronutrients present in groundnut, but I wonder how my ancestors discovered them first and figured out the different ways to preserve and enjoy them. Participant observation is a critical part of how knowledge is passed down among the Tonga, and we are a culmination of all that comes before us. Ifisashi has held us together for centuries, and it is what we will share beyond migration. We are our own archives.

Images courtesy of Banji Chona in collaboration with, Women’s History Museum and Swedish Ethnographic Museum