In Zambia, marriage isn’t complete without lobola, the centuries-old tradition of bride price. But as modern pressures rise, so do the questions: Is lobola a sacred bond between families, or does it trap women in oppressive marriages? From soaring costs fueling child brides to men decrying financial strain, this deep dive examines whether Zambia’s most enduring marital custom is a unifying force—or a system in need of reform.

In Zambia, marriage isn’t just about the big white wedding—it’s a whole journey of traditions, and lobola is a huge part of that. From the proposal to the Chilanga Mulilo drums and Bana Chimbusa rituals, Zambian weddings are packed with meaningful traditions. One of these is the practice of bride price, or lobola, with many Zambians not considering a marriage authentic unless lobola has been paid.

But as the country moves further into an era where it must decide which cultural practices to preserve and which no longer serve a fruitful purpose, is dowry the next tradition destined for the chopping block, or is its cultural importance too deep-rooted to let go of?

Lobola’s Origins: How Bride Price Started in Zambia

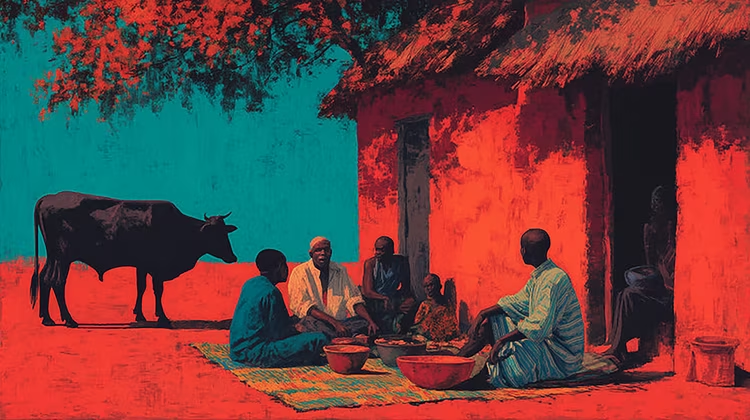

Nobody knows exactly when lobola originated—its pre-colonial origins are unclear—but we do know it has been around for centuries. The tribes that practised it include (but are not limited to) the Tonga, Bemba, Lala, Mambwe, and Namwanga tribes—each with its variations on the lobola process as well as its meaning. Simply put, lobola was a payment from the groom’s family to the bride’s—a way to honour her upbringing, compensate her family, and unite the two households.

What Was Traditionally Paid as Lobola?

- Livestock (cows, goats).

- Farming tools.

- Handcrafted gifts.

- Other valuable goods.

With this payment came the formal recognition of the marriage, and any children born of the union were considered legitimate. There were also several traditional ceremonies, many now frowned upon or no longer practised, that could not be initiated without the full payment of lobola.

Lobola Today: Cash, Conflict & Changing Traditions

In modern-day Zambia, lobola has achieved the unusual feat of spreading with the country’s advancement, rather than diminishing. Bride price is now more widely practised than ever. While this is partly due to more frequent intermarriages between tribes, one could argue that such an age-old tradition could only surge in popularity if it offered something people feel is missing from their modern lives. As Zambians become more educated and increasingly exposed to the wider world, the question arises: What is it about lobola that compels people to set aside modern trappings and return to a tradition long practised by their ancestors?

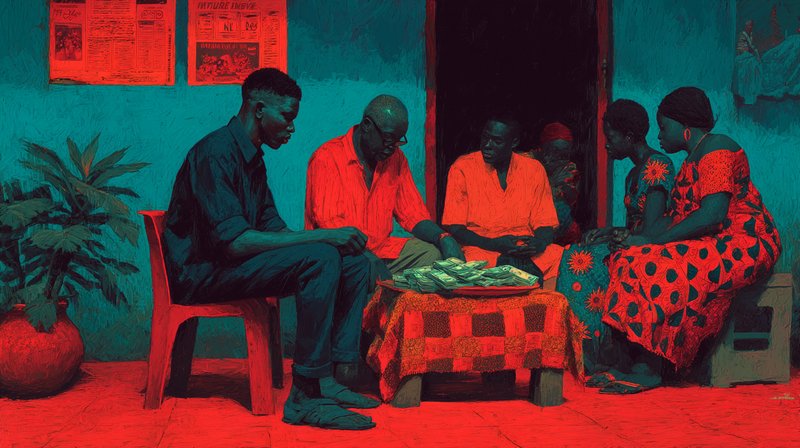

Champions of lobola say lobola offers stability in changing times—but it’s also evolved. Once a family effort, it is now often just the groom’s burden, with cash replacing cows and mobile money speeding up payments.

No Zambian tribe calls lobola “buying a wife”—but when cash changes hands, she takes his surname, and her virginity or education hikes the price, it starts to feel like a transaction. And while the cultural intention of lobola is to unify two families, if the practice itself creates discord between the sexes, how unifying can it truly be?

Many men see lobola as a financial burden, especially with rising costs and stagnant wages. But if a man can splurge on a PlayStation or a car, yet baulks at saving for lobola, is the tradition the problem? Maybe it’s about priorities.

Studies in some Zambian communities suggest that lobola promotes honour and respect within marriage. It is seen as a gesture of the groom’s appreciation for his bride and her family, elevating the bride’s status and symbolising his commitment. Lobola is often interpreted as an act of love, a symbolic tradition that reinforces mutual affection between the couple.

However, when we step back from the personal, lobola reveals itself as a contributor to far broader and more harmful societal issues. Poverty fuels Zambia’s child marriage crisis (29% of girls wed as minors). For struggling families, lobola becomes a survival tactic—even though it traps girls in harmful unions, costing the economy millions.

How Lobola Can Harm Women:

Some men see lobola as "buying" a wife, leading to control and abuse. Women report restrictions on finances, clothing, and even basic freedoms. Studies link lobola to higher rates of domestic violence. Gender-based violence connected to the bride price remains one of the most pressing concerns. Research consistently shows that the act of paying lobola reinforces patriarchal ideas of male authority within marriage. Husbands may expect total submission from their wives, and any perceived defiance can result in mistreatment, both from the husband and his extended family.

Moreover, lobola can create major obstacles for women attempting to leave abusive relationships. Traditionally, lobola must be returned in the event of a divorce. For many women, especially those without financial means, this repayment is impossible, leaving them feeling trapped. The issue is compounded within customary marriages. Zambian unions fall under either statutory or customary law—a division rooted in colonial legal frameworks that continues to carry real consequences. Customary marriages are not legally recognised unless lobola has been paid, even after many years of cohabitation. Often, people only discover this when trying to dissolve their marriage in local courts, where they may be denied legal recognition or access to maintenance. As previously noted, if lobola was never paid, the marriage is not considered valid under customary law, meaning women may walk away with no legal protection or support at all.

Turning Tradition into Progress

A study by the International Growth Centre found that lobola amounts tend to increase with the bride’s level of education. This suggests that bride price may indirectly encourage families to invest in their daughters’ education, offering a small but important developmental incentive.

If we use lobola to encourage girls’ education—like paying more for educated brides—it could turn an old tradition into a force for good. And maybe that is what is needed in the lobola debate and the country in general: finding a way to work without cultures and traditions that hinder our advancement.

Lobola’s Future With just over 60 years of independence, Zambia is still in the process of reclaiming and redefining traditions that were once dismissed or suppressed under colonial rule. Cultural practices, lobola included, derive their meaning and impact from the context and intentions of those who practise them.

Whether lobola becomes a symbol of unity or a source of oppression depends not only on the families involved but also on the society in which they live. As Zambia continues to shape its identity, the challenge lies in ensuring that cherished traditions do not come at the cost of dignity, equality, and human rights. We don’t have to throw tradition out—but we should question it when it holds us back.