Phiri would later establish Kwacha Photo Studio in 1983, creating an extensive archive of black-and-white portraits that captured the everyday realities and dignity of Lusaka's residents during Zambia's post-independence era.

The Barriers to Photography in 1960s Zambia

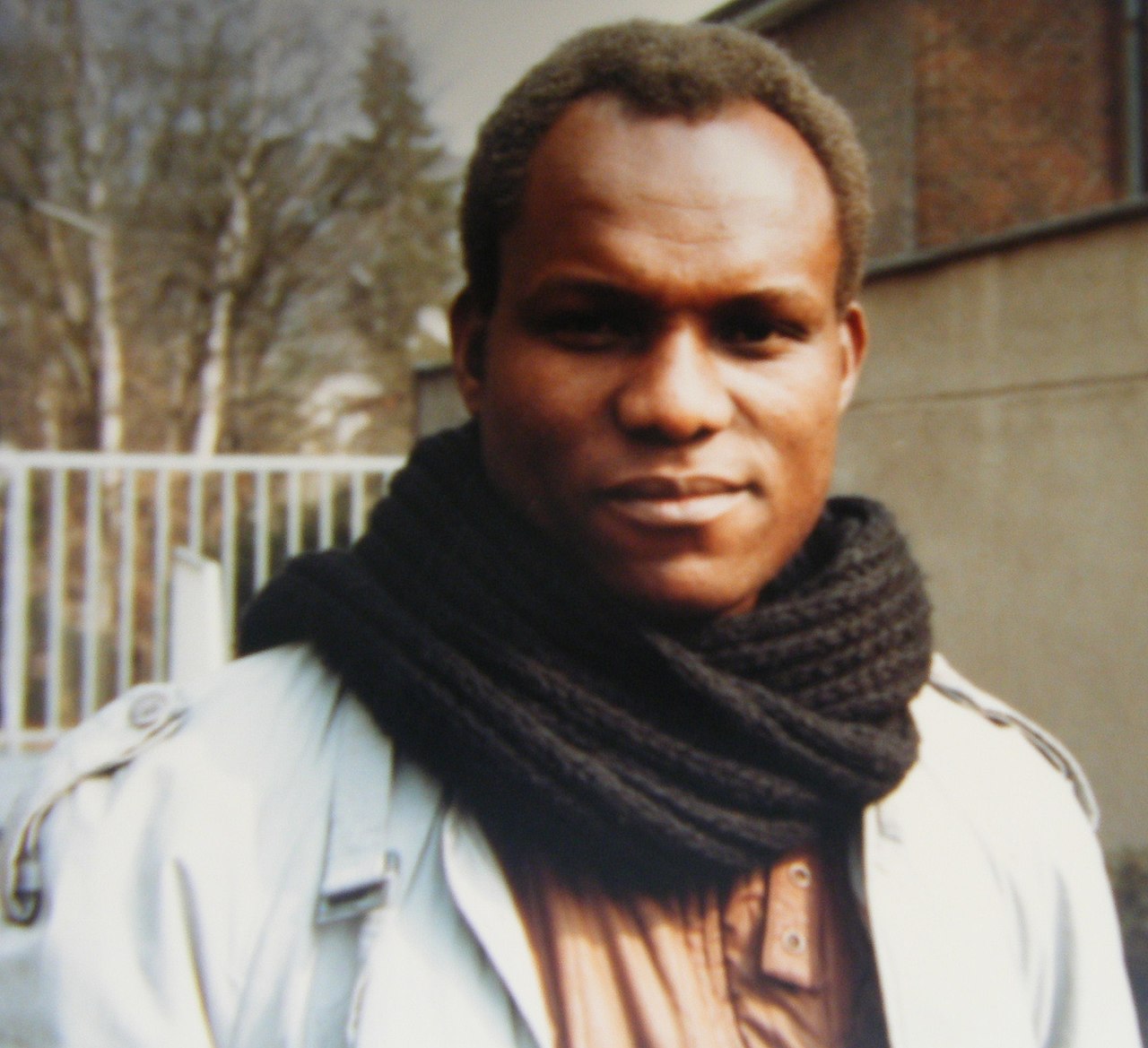

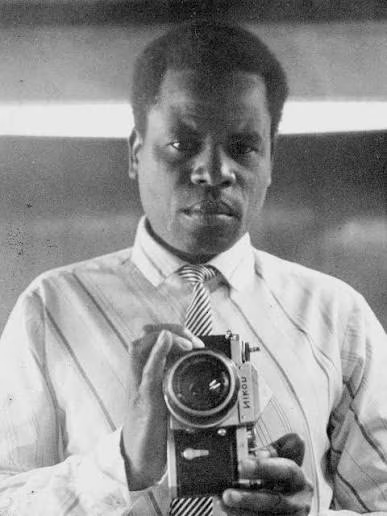

In the mid-1960s, photography was foreign to many Zambians for two clear reasons. Firstly, it was not something expected of Zambian natives under the remnants of colonial restrictions and segregation. Secondly, photography equipment was prohibitively expensive then, as it still is now. But a curious young man named Alick Phiri stepped into the frame, led by curiosity. At just seventeen, he stepped foot into Lusaka’s Photo Art Studios on Cairo Road, where he became the youngest assistant. Under the mentorship of Mr. Prabhubhai Patel, he learned the art and craft of photography and film development, a passion that grew exponentially. Photography had stolen Alick’s heart.

These early years were a gate that opened a whole new world that was still a distant reality for many Zambians. To step into a dark room, to understand the intricate science of light and film, to hold and use a camera correctly, you’d only imagine the wonder this sparked. Sadly, at the time, access to this magical world was a privilege few could enjoy, save for settled Europeans and a handful of Indian-owned studios in Lusaka. For Alick, wielding this knowledge became a responsibility: to carry the torch of practice in a way that truly reflected the faces and lives of the majority who had long been excluded from its frame.

The Foundation of Phiri's Career

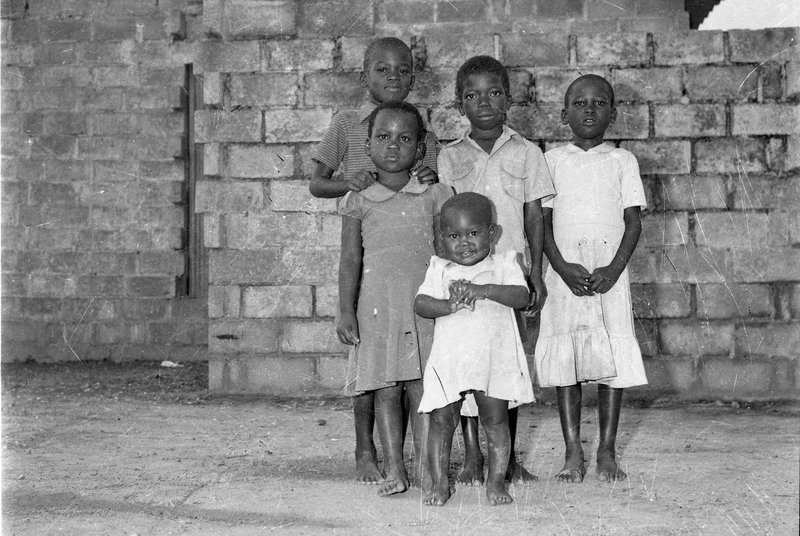

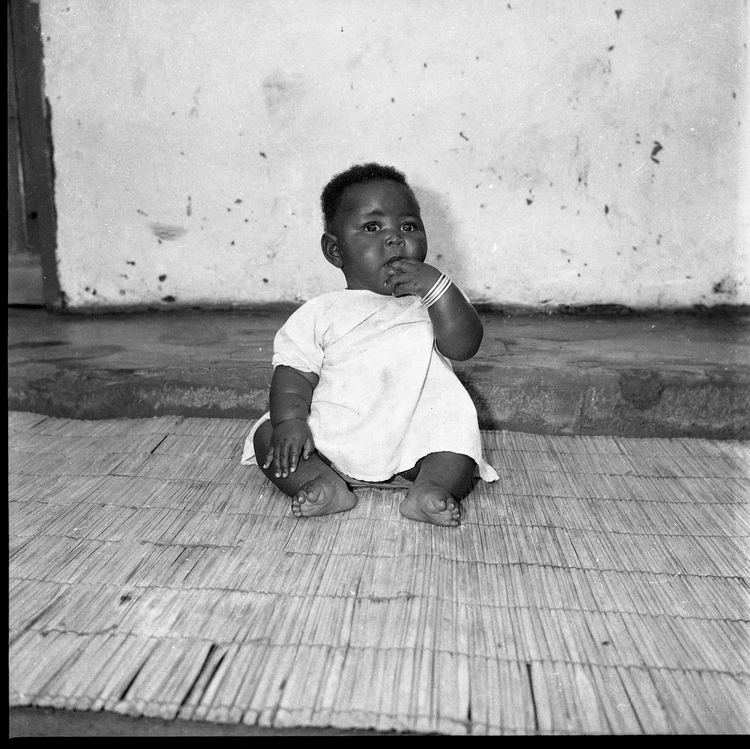

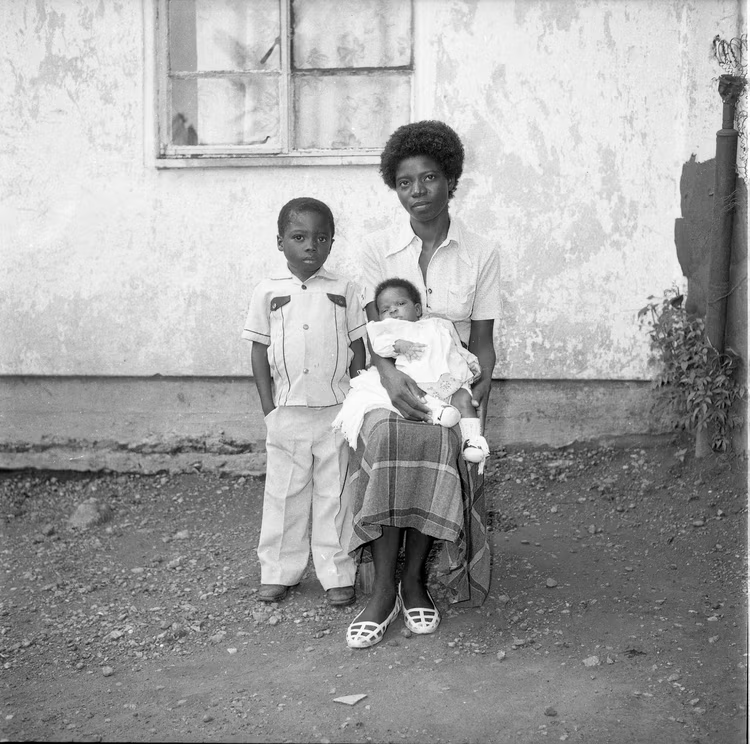

In 1983, Phiri opened Kwacha Photo Studio in Kanyama. “Kwacha,” meaning dawn, was not an accidental name. It echoed the hope and promise of Zambia’s independence. At a time when very few Zambians had access to professional training in photography, his studio became one of the first Zambian-owned spaces dedicated to documenting the everyday lives of black Zambians. Scores of people gathered outside their homes in Sunday best, friends paused in the streets, and children leaned curiously into the lens. Phiri captured them all, creating portraits that spoke not only to personality but also to the quiet dignity of Lusaka’s post-independence years. For the first time, Zambia was camera-ready, on its terms.

For nearly three decades, Phiri’s lens became a witness to the ordinary and the extraordinary. He photographed families and friends within their homes or streets, sometimes capturing candid moments: a group of siblings assuming a quirky pose beneath a wall sign, a mother holding her child against a brick backdrop, a couple holding hands earnestly. These images bore witness to a new age of independent Zambia and collected many firsts that nobody had captured before.

Archiving Zambia's Visual History

In an era where archives were scarce and visual histories even scarcer, Phiri’s work stands today as one of the rare windows into urban Zambia from the 1960s through the 1990s. His photographs captured a capital in transition and a living, breathing city of people whose lives transitioned with it. The clothes, the postures, the smiles, and the seriousness are all fragments of memory preserved in silver grains of film.

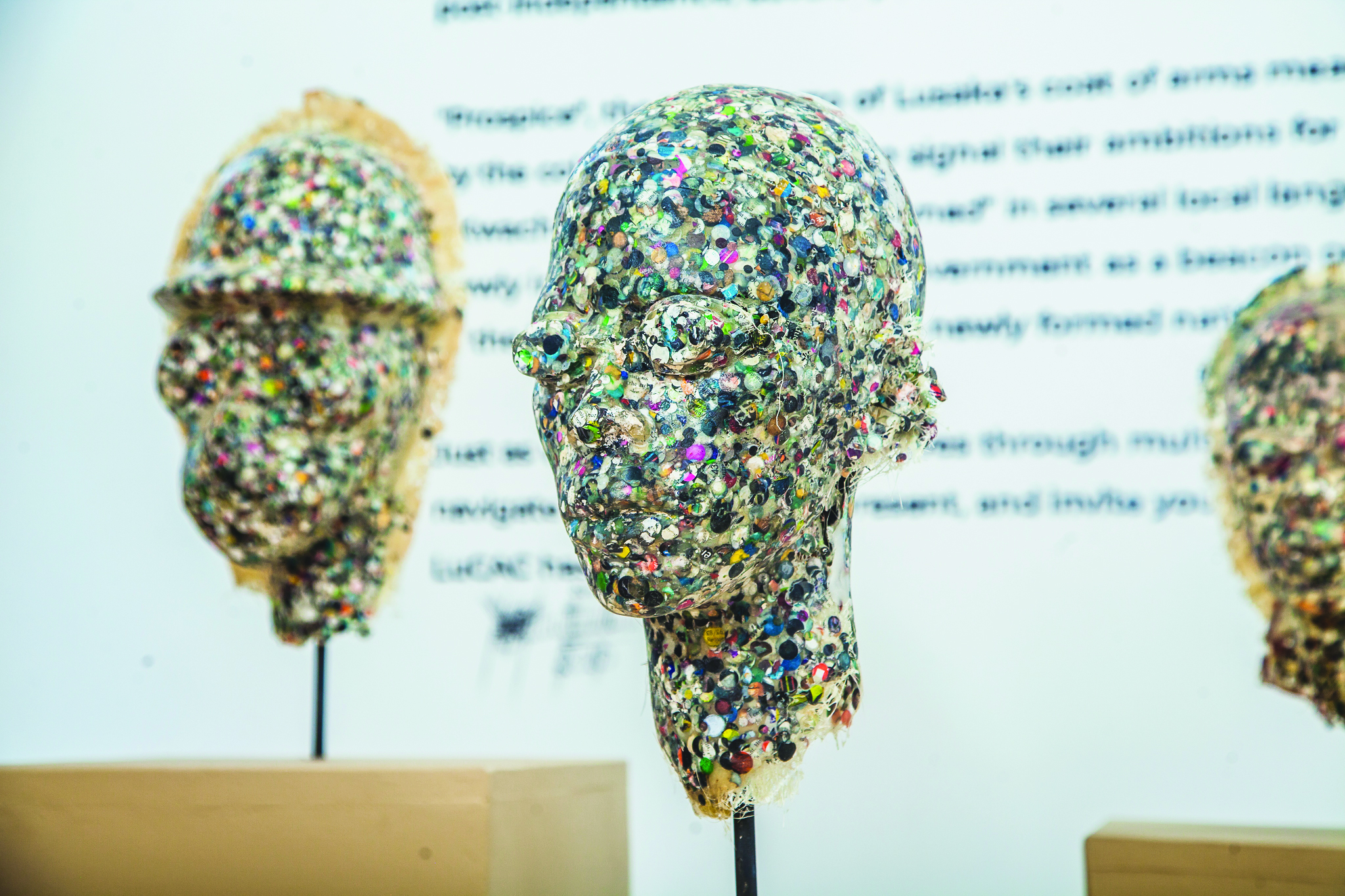

For a time, this archive was stored away, but in recent years, it has found new audiences and renewed recognition. In 2024, Phiri’s photographs were shown internationally at the 14th Bamako Biennale, “Kuma.” His work was also published in the photo book Lusaka Street, authored by Sana Ginwalla, bringing his images into the hands of readers who had never seen Lusaka’s past through such an intimate lens. And for the first time in Zambia, his archive was exhibited at the inaugural Bakashimika International Photography Festival.

The significance of this moment cannot be overstated. At seventy-seven, Phiri is one of the few surviving professionally trained Zambian photographers from his generation. Recognising his work on Zambian soil, the faces of his audience mirrored in his visual archive, is a reminder of how art is not isolated, but carries history forward.

Phiri’s poignant imagery calls us to our own histories, to preserve them with care, and to keep building visual records that future generations can stand on with pride, whether through photographs, paintings or African art. The record lives on.