How do simple roots and maize transform into something so dynamic, so deeply tied to culture and survival? Whether you grew up with these flavours or are discovering them for the first time, the story of Munkoyo and Chibwantu is a testament to the wisdom embedded in the soil, the roots, and the hands that stir the pot.

When I was little, the highlight of December was my great-aunt's arrival from Chipata. She always stepped off the bus with an opaque drink tightly secured in an old cooking oil container, and I knew that bottle too well, cradled like treasure: her famous Munkoyo. Nobody knew how she made it, but everyone knew it was alive in a way that was curious and somewhat eerie. One year, the container looked as if it was breathing, swirling inside like it was thinking about its great escape. My cousins and I stared at it in awe until curiosity and intrusive thoughts got the best of me. I loosened the lid, and in an instant, the whole thing erupted like a rush of foam, a loud pop spreading to the ceiling. My uncle ran in, eyes wide, but not to check if I was okay. He just gasped, “My glorious Munkoyo is gone!” I didn’t understand then, but I know now that what exploded that day wasn’t just a drink; it was a living brew carrying generations of knowledge. Most Zambians have a special story to tell about Zambian local brews that bring back fond memories such as these.

How is Chibwantu Made

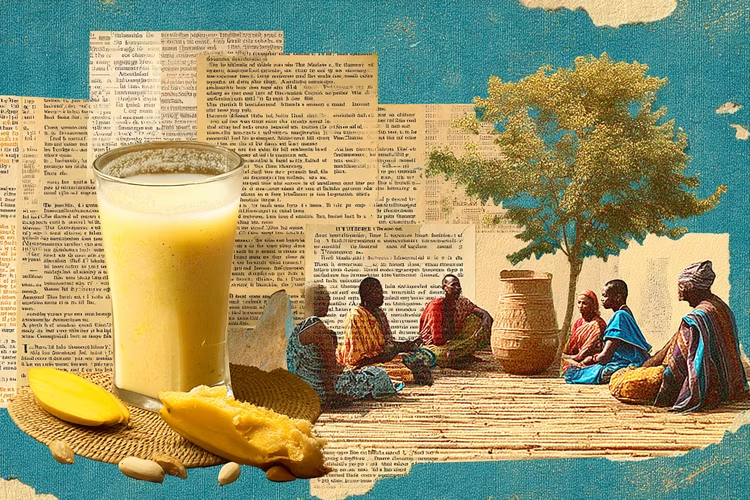

In Zambia, two drinks hold that kind of spirit: Munkoyo and Chibwantu. They are alive in several ways: thirst quenchers, celebratory drinks, and curiously in the microbial sense. In a way, they carry stories, rituals, and regional pride. Munkoyo begins with maize porridge, boiled and thick, then cooled just enough for roots to be added. These aren’t random roots but most commonly roots from the Rhynchosia genus, often named in the literature as Rhynchosia venulosa or Rhynchosia heterophylla, whose fibres are rich in natural amylolytic enzymes. They break the maize starch down into sugars without any fancy machinery. Give it a day or two, and you have a smooth, tangy drink. If you leave it longer, it grows sharper and sometimes gently alcoholic, though most families in the village stop the process early so everyone, even children, can drink it. People swear by its ability to refresh after farm work, to settle the stomach, and for new mothers, to help with milk production.

Chibwantu shares the same soul but is heartier, almost gritty, made with coarser maize and often a slightly different root treatment. In some districts, the root is steeped in water to make an extract, in others, the whole root is tossed into the porridge; the variations are part of the point. Other species and local plants, such as Eminia and Vigna relatives, are sometimes used as well, which helps explain why households and regions produce such different flavours. In Southern Province, it’s a drink for gatherings, for sitting in a circle with neighbours, and for passing around a cup while the conversation drifts from crops to cattle to who’s getting married next. Like Munkoyo, it’s made without sterile factories or packaged yeast; the microbes come from the air, the vessels, and the roots themselves. That’s why it tastes different in each household. Some brews are sweeter, some more sour, and some with a faint earthy bite. I’ve had Chibwantu so fresh it was still warm from the pot, and I’ve had it after three days of resting, cold and complex, the way older folk like it.

Munkoyo, a Wild Brew

Behind the easy laughter of sharing these drinks is clear-cut science. As the roots interact with the maize, lactic acid bacteria are activated and make the drink safe by lowering its pH so harmful germs can’t thrive. They also give it that gentle tang that makes your mouth water for another sip. Alongside them, wild yeasts turn some of the sugars into tiny amounts of alcohol and layers of aroma. I, for one, will always wonder how we instinctively know when the brew is ready. But maybe it’s just one of those things you “just know” as a child of the soil. Maybe it’s felt. It’s felt in the smell of the bubbling pot, the look of the surface, and the sound of a satisfied gulp. In a world obsessed with precision, these drinks are reminders that mastery can be passed through memory, through taste, and through watching someone’s hands move in a certain way.

Even in towns, where you can now find bottled “Munkoyo” on supermarket shelves, the village versions remain unmatched. The commercial ones are tamer, sometimes pasteurised, and their life is arrested for the sake of shelf stability. But the traditional ones are still alive in your cup, literally changing with every hour. They are nutritious as much as they are cultural, delivering good bacteria to the gut and energy from natural sugars, and in the case of Chibwantu, that satisfying weight in the stomach that can keep you not only hydrated all day but satisfied too.

When I think of my great-aunt’s Munkoyo now, I see it as a little piece of that heritage: unpredictable, strong-willed, and sentimental. We live in a time where food is engineered to look, to last, to taste the same every time. Munkoyo and Chibwantu refuse that. They are alive, and like anything alive, they are at liberty to bear different personalities. One day, they might be calm and sweet; another day, they might explode in your hands. I love that these drinks are not made to be a “one size fits all” type of beverage. And maybe that’s part of the joy.