The Lusaka Playhouse is more than a decaying building; it's the heart of Zambian theatre. But can passion alone save it? Let's go behind the scenes of the iconic landmark, moving beyond the public debates to uncover the real financial struggles threatening its future. Discover why this national treasure is renting space to shops and a church, and why its survival depends on more than just nostalgia.

The Lusaka Playhouse has been visited by movie stars and graced by English royalty. Its rafters have witnessed the rise of some of Zambia’s greatest theatrical talents and hosted some of the most brilliant plays the nation has produced. From when our country was a colonial outpost to the moment it became an independent democracy with its own flag to fly, the Lusaka Playhouse has stood at the corner of Church Road.

But a building cannot play such an integral part in a city’s history without bearing the marks of time, and the Lusaka Playhouse is no exception. Its physical decay has become both a hallmark and a landmark of the city’s past, while also symbolising the theatrical aspirations of its future. This duality has made the Playhouse a focal point of contention among the media, arts lovers, and residents, culminating in public outcry several years ago when it was announced that the Playhouse was in (now voided) negotiations to rent part of its premises to a fuel station.

The Visible Decay of a National Stage

As I enter the building, my first instinct is to agree with what I’ve read and heard before—that the stakeholders’ main interests lie less in advancing theatre or preserving a historical relic, and more in securing rentals. This impression seems confirmed by the numerous services on the premises selling things unrelated to theatre, though they’ve created their fair share of drama for the Playhouse itself: a plant shop, an internet café, a bar, and a restaurant. The paint peels in some areas, and the ceiling is waterlogged in others.

But after meeting and engaging with the theatre director, Mr Dominic, my perspective shifts. I realise, like many others, I had fallen into the trap of assuming that goodwill and vision alone could sustain the arts. This building, constructed in the 1950s and originally intended for the small white population, cannot be adequately maintained, stage, lighting, seating and all, in an economy that has only recently begun to see the arts as both a viable industry and something worth investing in.

Inside the Lusaka Playhouse

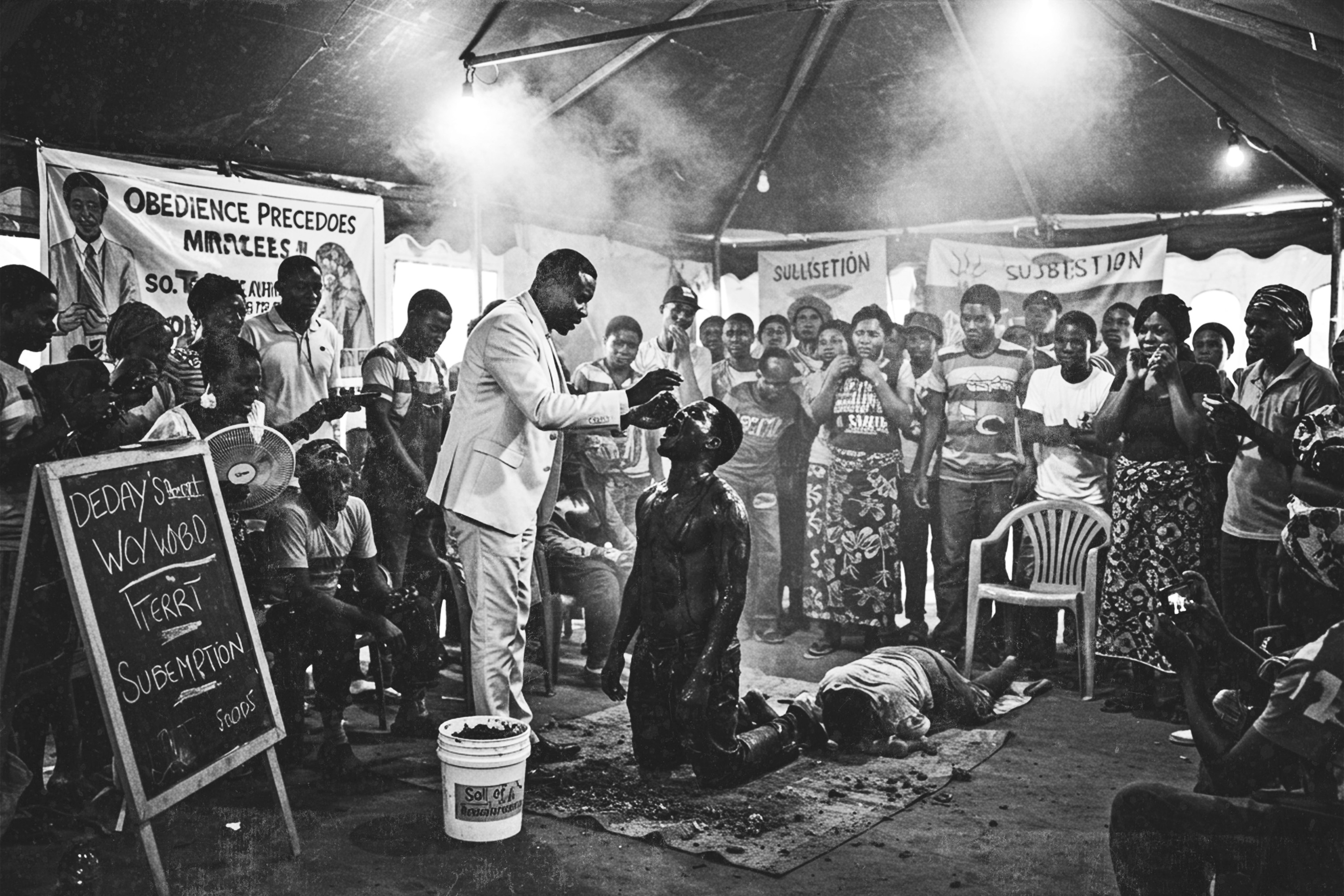

As Mr Dominic shows me around—the 250-seat auditorium, the orchestral pit, the 8x12m stage, and the rehearsal room—I sense not an organisation doing the bare minimum, but one striving to produce at its maximum with very little to work with. He is frank about funding being the theatre’s greatest challenge. This is why, on Sundays, the rehearsal hall doubles as a church, and why spaces on the premises are rented out to various businesses.

Most actors in Lusaka need day jobs to survive. Even the few who have managed to make acting a full-time career juggle TV work during the day and theatre rehearsals (often at the Playhouse) at night. The business of performance here yields minimal reward, and in Zambia, it runs far more on passion than profit. But passion cannot pay electricity bills, replace stage lights, or reupholster seats. It cannot cover costume designers, repaint walls, or repanel ceilings. It cannot restore the building to the standard it once had, when Zambia’s greatest theatre legends honed and performed their craft here - even as today’s rising talents contend with its decline. The theatre manager proudly tells me that “no one can talk about acting in Zambia without having passed through the Lusaka Playhouse,” yet he also laments the challenges of funding and the lack of willing partners. He describes a vision of a Playhouse that maintains its historical integrity while being updated for both capacity and aesthetics.

The Future of the Lusaka Playhouse is in Our Hands

My glimpse behind the scenes of the Playhouse left me with a new set of questions. Not about what the city owes us, but what we owe the city - the streets, the malls, the landmarks that shape it. We can claim to despise littering, but what does that mean if we never join recycling projects or donate bins that would help? We can complain about the state of Zambian literature, but, as popular online book reviewer Sumili Kipenda asks, “Are you reading Zambian?” And we can shake our heads in dismay at the current state of the Lusaka Playhouse while never donating our time, money, or even attendance to boost ticket sales. Whether the curtains close on the Playhouse, or rise again more prestigious than ever, is entirely in our hands.