This is the story of the Valley Tonga, it is also the story of Nyami Nyami, the serpent-river spirit whose legend refuses to be drowned, in spite of the rising waters of the Kariba Dam.

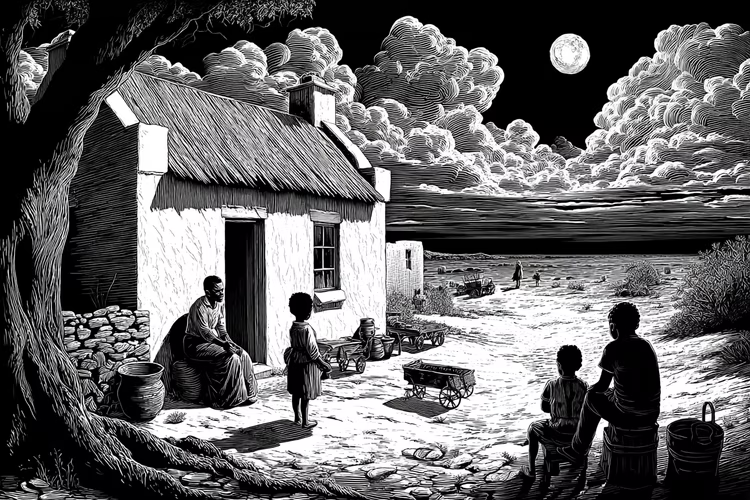

Lake Kariba is famous today for its sunsets, its vast waters stretching across the horizon, and its appeal to tourists who come to fish for the famous photogenic tigerfish, sail, and rest on its islands. But beauty is only what the eyes see on the surface. Beneath those waters lies a valley that once nurtured life, a place of villages and fields where children played, elders told stories, and people farmed. The Valley Tonga remember it well. To them, the Zambezi is an ancestor who watches and protects them. When the dam came, the ancestors were trapped; with them, their people’s homes, graves, and memories sank out of sight.

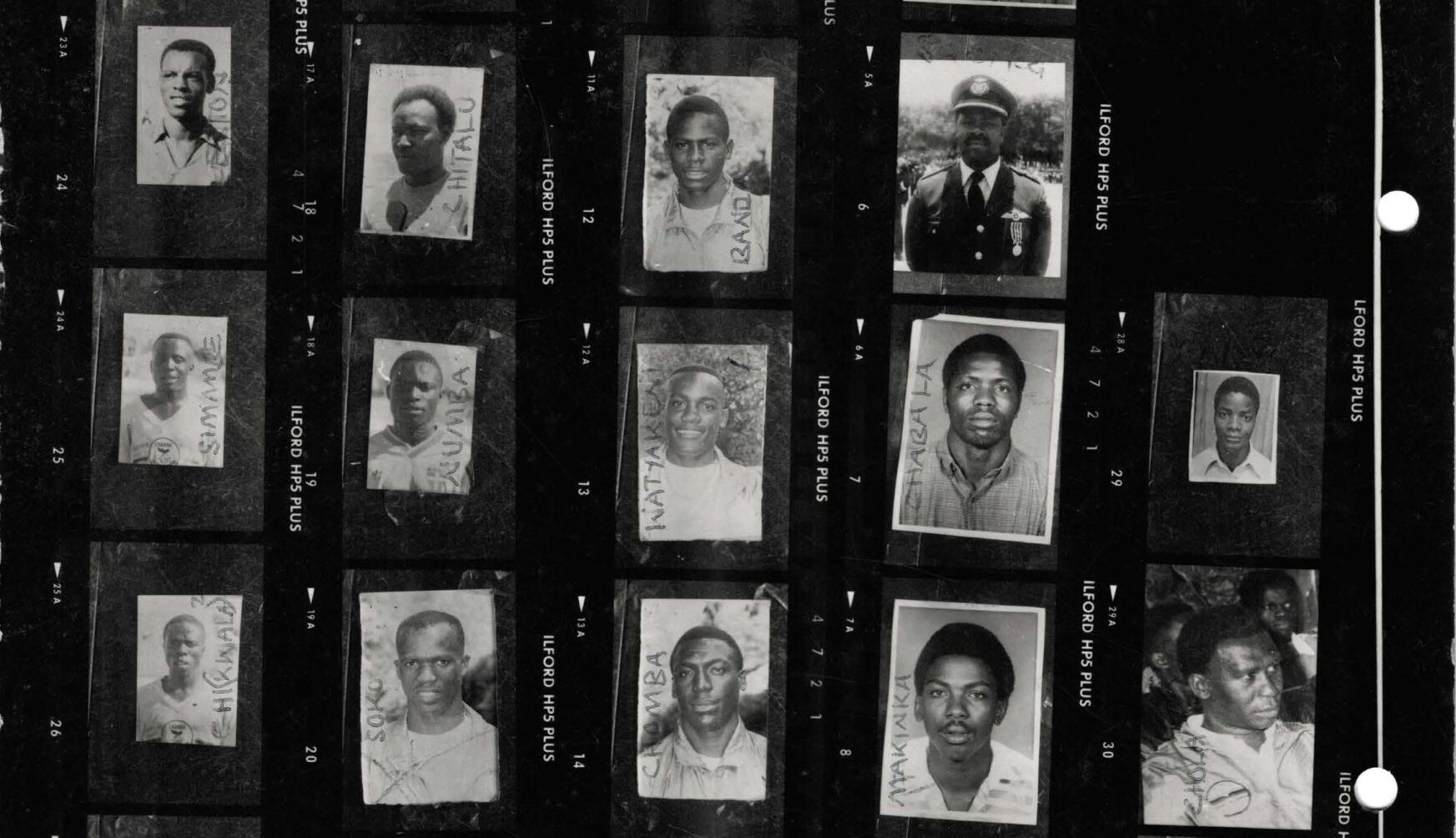

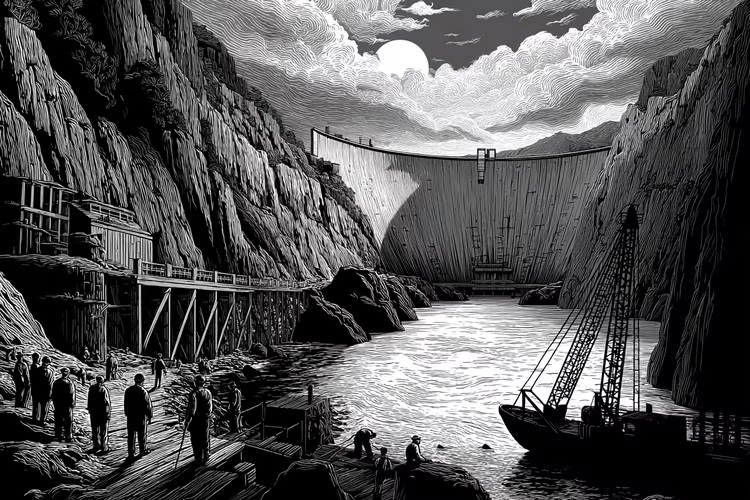

It was called progress, and in the 1950s, the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland wanted electrical power, and the Kariba Dam promised to deliver it. Concrete, steel, marvels of technology, and machinery arrived in the valley, pushing aside the people who lived there for generations. Nearly 60,000 were relocated. Some went willingly, eager for new life and development, while others reluctantly left behind cattle, farmland, and even the bones of their kin. The regime named it ‘resettlement’, but the Valley Tonga called it ‘loss and betrayal.’

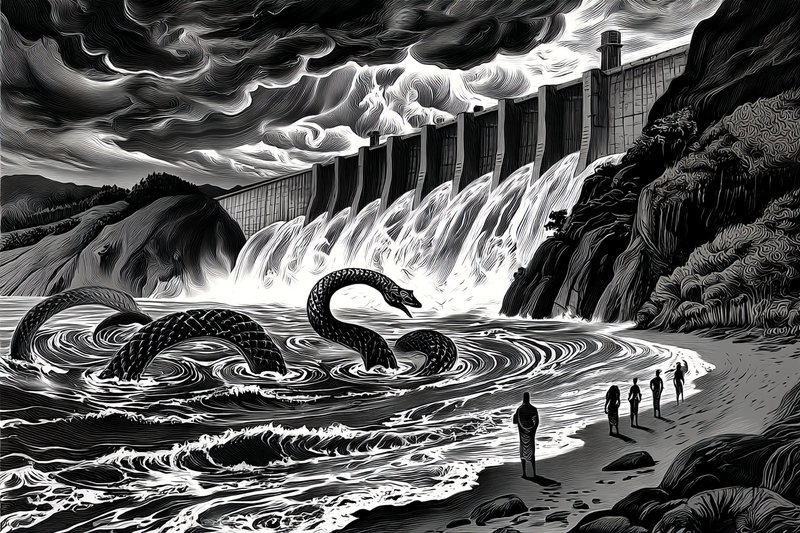

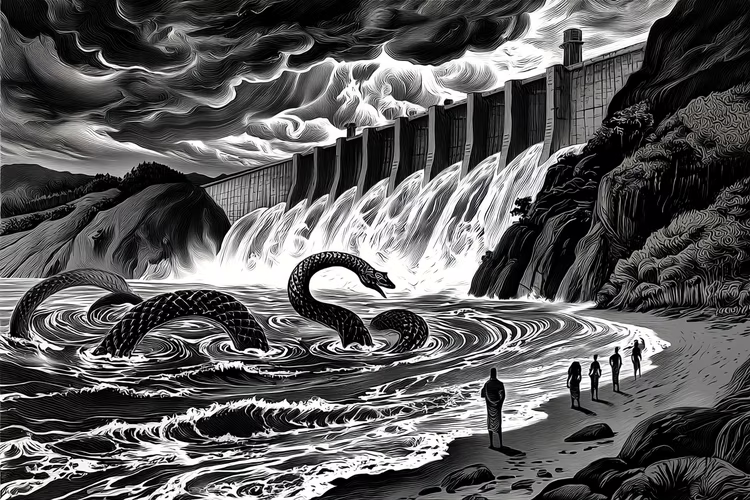

The story of Kariba cannot be told without the river spirit, the Nyami Nyami. The Valley Tonga believe he lives in the depths of the Zambezi, a serpent-like protector with the head of a fish and the body of a snake. He gave them food in times of famine, guiding their nets so the river never ran empty. But when the dam began to rise, Nyami Nyami was cut off from his wife, who lived on the other side of the gorge. The earth shook more than once, as if in anger. Workers whispered that it was him, thrashing against the barrier. Some died in accidents that could not be explained, and the river swallowed them without returning their bodies. Yet, still the dam grew higher. Each block of stone and cement sealed the fate of the valley. Villages vanished beneath rising waters, fields turned into mud, and memories vanished to a place no one can follow.

But water does not simply cover land; it transforms it. The valley became a lake, the largest man-made reservoir in the world at that time. Yet for the Valley Tonga who had made it their home, the glimmer of the surface was a reminder of what lay beneath.

The resettlements were not the paradise that was promised. The soil was rocky and hard, the rivers small and unreliable. A people that had once thrived along the fertile banks of the Zambezi found itself struggling with hunger. They were told to adapt, to make do, and to start afresh. And that they did, grinding bones to make soup, foraging for wild fruit and plants.

The dam became a symbol, admired by engineers across the globe as a triumph of modern design. It stood as proof of what human ambition could achieve when it challenged nature. But for the displaced Tonga, it was proof of something else entirely: that power can bury people as easily as it lights cities.

And Nyami Nyami? His legend did not sink with the valley. Each tremor, each flood, each strange turn of the waters has been tied back to him, perhaps waiting for the day when he will break through the dam wall, reunite with his wife, and restore balance to the river.

Today, we gaze on the Lake and call it beautiful; we are not wrong. But beauty here is complicated. It is the beauty of sunsets reflected on water that covers history. The beauty of silence where laughter once rose. The beauty of progress built on sacrifice. The Lake stretches wide, a shimmering mirror of ambition, yet its depths are receding, revealing once again the fragile bones of promises as the windows of modern homes sit, unlit, in the shadow of an ongoing energy crisis.

Nyami Nyami’s watchful eyes are patient. He has seen civilisations rise and falter. The world calls it a marvel, but the valley remembers differently.