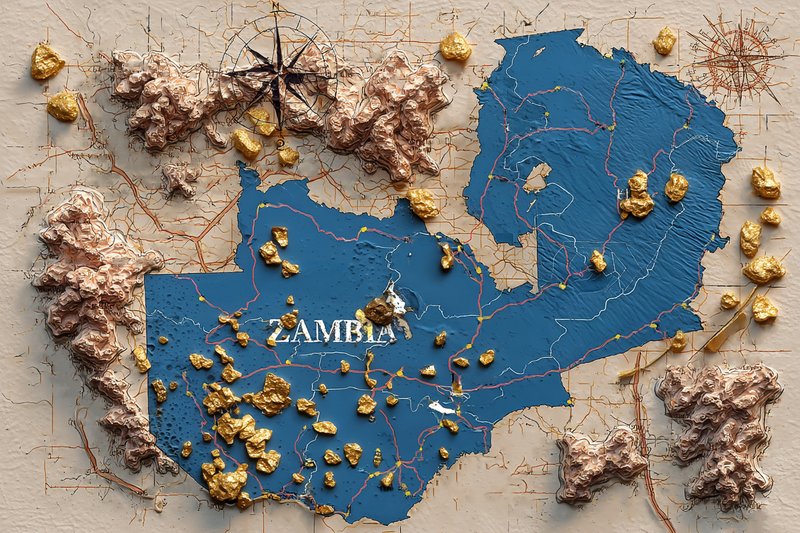

Driven by poverty and hope, thousands of Zambians are engaging in illegal, small-scale gold mining. This modern-day gold rush presents an opportunity for individual fortune but carries significant risks, including environmental damage, violence, and exploitation by criminal networks. While the government attempts to clear the sites, the miners' desperation highlights a deeper crisis and the need for regulated solutions rather than forceful evictions.

A woman in Petauke had a dream. With the same small hoe and shovel she used for farming, she began to dig. She toiled through the dirt, rock, and soil of the yard where she usually only grew vegetables. Four days later, her green chitenge now streaked brown, she emerged from the garden with what she had dreamt of - a nugget of gold in her hand.

What sounds like folklore is reality in places like Petauke and Mufumbwe. One person’s lucky strike and the promise of rags-to-riches that comes with the mineral have drawn thousands to once barren land. What used to be farmland now teems with tents, vendors, and hopeful people. Young and old. Makeshift settlements overflow with both the hunger for gold and the hope that it will transform their lives.

Death, Pollution and Mercury Poisoning

Zambia is no stranger to mining. Our economy has long been driven, often painfully, by its reliance on copper and the global price of the mineral. We have the Copper Queens, the Copperbelt, and even the orange hue in our flag to remind us of it. Our blood practically runs copper. Yet the mining industry that sustains our nation has largely remained in the hands of foreign investors or companies so wealthy and distant that they feel far removed from the lives of ordinary Zambians. Where copper tied Zambia’s fate to boardrooms far away, gold has brought a more immediate, if fragile, promise: the chance for ordinary citizens to dig for their own fortune.

And dug they have, with a ferocity and desperation that raises concern for both the earth being mined and the people mining it. The majority of people at sites have no prior knowledge or experience with mining, nor do they have the necessary safety equipment. Some sites have even experienced mine collapses resulting in death and injury. Government spokesperson Cornelius Mweetwa told reporters that illegal mining has fuelled the smuggling of minerals and environmental pollution. Additionally, toxic waste from illegal mining is deposited directly into water bodies, contaminating them. On the Copperbelt, illegal mining in Chingola has left its mark, polluting the Kafue River and the water sources that people depend on. Small-scale miners often turn to dangerous methods like using mercury or diverting entire waterways, putting both people’s health and the environment at risk, not to mention the general risks that come with having any large number of people in an area with neither the ability nor the sanitation needed to accommodate them.

Violence and Control at the Mines

It was with this in mind that the police began their clearing operations. Recently, four days of clashes at the Kikonge site in Mufumbwe left three miners dead and five police officers injured. But the risks of violence do not only come from the police trying to clear the site; they also stem from the way the site operates. With no regulation and no clear authority, gangs have stepped in, seizing any significant gold finds and enforcing control through fear.

Who is Really Buying Zambia’s Illegal Gold?

And who is buying the gold? The answer is shrouded in secrecy, even though the average Zambian has little use for the mineral. Cashing it in is reportedly handled by a chain of middlemen, acting for foreign traders arriving in unmarked cars, striking swift deals, and vanishing just as fast. Minister of Mines Paul Kabuswe warned, “We will not allow gold to slip through our fingers and be bought cheaply by people who smuggle and don’t pay tax. We want to secure the place. This is the country’s wealth … All this wealth belongs to Zambia.” Yet one attempt to clear Kitonge revealed a more complex network: over 20 vehicles, 100 scanning machines, gold detectors, and firearms, some described as military grade, pointing to players with far more than ordinary ambitions.

Can Zambia Control Its Gold?

However, regardless of the broader implications, it is difficult to overlook the individual impact of the gold rush on the common people involved. The original lady in Petauke excitedly described how now she would buy a Fortuner and a Ford Ranger “like Mutale Mwanza” after she had found enough gold. And for Tonga farmers who were camping in the area due to the drought that had driven them out of the Southern Province, the discovery of gold turned what had felt like a curse into a blessing. With recent economic hardships in Zambia, driven by drought, loadshedding, and inflation, the suffering felt on an individual level is palpable. And though the ownership of the land, and by extension the gold beneath it, remains in question, it seems more effective to train and educate informal miners than to try to stop them entirely. After all, the issue was created by the government's failure to set up a mineral regulator that covered the entire country.

The efforts to clear the sites remain with the police, stating that security reinforcements will be sent in. But despite the carnage, it is easy for one to understand the hesitance of the miners to leave the site. Most of their lives have been consumed by both poverty and the labour required to try to escape it. Now they have found gold in the soil they have been toiling through their whole lives - how could they possibly let it slip through their fingers?