From dollar-denominated lodges to foreign-owned safari camps, Zambia’s natural wonders have become a luxury reserved for outsiders.

There is a side to Zambia that is visible only to those who can afford it, exposing a deep divide in access to our country's most celebrated natural treasures. Ironically, this hidden side is the one we showcase with the most pride: the smoking thunder of Victoria Falls, the serene scenes of the lower Zambezi, and the majestic woodlands of Kafue. These are the images featured in posters that invite people to discover Zambia and explore "the real Africa." They are the visions that appear on National Geographic. Though they are our natural heritage, passed down by generations before us, for most present-day Zambians, this paradise exists only on a TV screen. The main argument of this piece is simple: for too many Zambians, the cost of experiencing their homeland has become an insurmountable barrier.

Our tourist destinations serve guests with nshima and bream. They teach them the correct way to tie a chitenge and say a few words in Nyanja. They decorate the rooms with Zambian pottery, teach tourists the Bemba word for antelope, and employ musicians to serenade their dinner with Zambian drumbeats. They package and condense the country's culture into digestible bites as a tourist experience, while blocking off the beauty of those sites from the citizens themselves.

There is an understanding in Zambia that the best of it is not accessible to locals, that if one wants to see one of the seven wonders of the world that happens to be located in your backyard, it is best to earn foreign currency. 2024 data showed that the country received 530,110 local tourists compared to 2.19 million international tourists. Meaning that for every Zambian who was able to tour their own country, more than four international tourists were doing the same.

By merely taking a casual glance at the pricing structure for local holidays, some of the reasons for this disparity are glaringly evident. The standard for hotels and travellers' lodges is to charge in dollars, per person, per night. The majority of Zambians are cut off from accessing these holidays simply by being expected to pay in a currency they do not earn. A currency valued at such a high rate that, even for those earning well in kwacha, paying in dollars can set them back disproportionately. It all suggests that the system designed to showcase the country’s natural beauty was never really built with its citizens in mind.

Many of Zambia’s most prominent lodges, safari camps, and hotels are foreign-owned, particularly in areas like Livingstone, South Luangwa, and the Lower Zambezi. The establishments were built and paid for in foreign currency and are expected to generate revenue for foreign pockets. They price their businesses for people who look and earn like them, and when questioned, often justify their prices by listing all the ways the profits may benefit conservation, casting significant doubt on the line between gamekeeping and gatekeeping. As much as foreign investment is an essential part of any economy, if the times we are most likely to see Zambians in such places are when they are serving the food there, we have crossed the line from foreign capital flows to selling our heritage off to the highest bidder.

In an attempt to combat this, the Ministry of Tourism launched the Take a Holiday Yamu Loko Campaign in late 2024, partnering with tour operators to offer discounted packages, curated travel experiences, and encouraging Zambians to explore domestic tourism. There had been a slight initial success with its launch, coinciding with a 9% increase in domestic tourism. While the campaign represents a meaningful first step toward democratizing access to our natural heritage, there's still work to be done to address the larger structural issues of foreign ownership and affordability. The 9% increase in domestic tourism shows that when barriers are lowered, Zambians respond with enthusiasm. While some participating establishments may not match the luxury standards of high-end tourist lodges, this creates an opportunity for local entrepreneurs to develop quality, affordable accommodations that serve Zambian travellers without compromising on experience.

While we advocate for systemic change, we can begin exploring their heritage today through budget-friendly options: camping at designated sites near major attractions, joining community tourism groups that negotiate group rates, visiting during off-peak seasons when local discounts are more common, and supporting Zambian-owned guesthouses and tour operators who understand local economic realities.

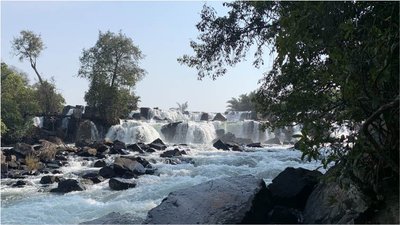

Change is possible, and it starts with recognising that our natural heritage belongs to all Zambians. While we work toward systemic solutions, there are immediate steps we can take. We can explore free experiences like hiking the Ngonye Falls trail, visiting local markets in tourist towns, or organising group trips to share costs. Community-based tourism initiatives are emerging, offering authentic experiences at accessible prices. The Holiday Yamu Loko campaign proves that when we prioritise our own people's access to their heritage, progress follows. Our wonders need not remain out of reach—with collective effort and creative solutions, we can reclaim our birthright one affordable adventure at a time.