From "utubasungu" praise to playground code-switching, discover how one language both unites and divides a nation still negotiating its multilingual identity.

There is a tool that was given to the Zambian people and is widely used and easily accessible to all. You carry it with you everywhere you go; some are fluent in using it, and some aren’t. A dialect is among the many tongues in our nation that found its roots in Colonisation. It’s easy to use, free, and it has been declared the official tool that acts as a bridge that eases translation.

The English tool.

Language and Identity

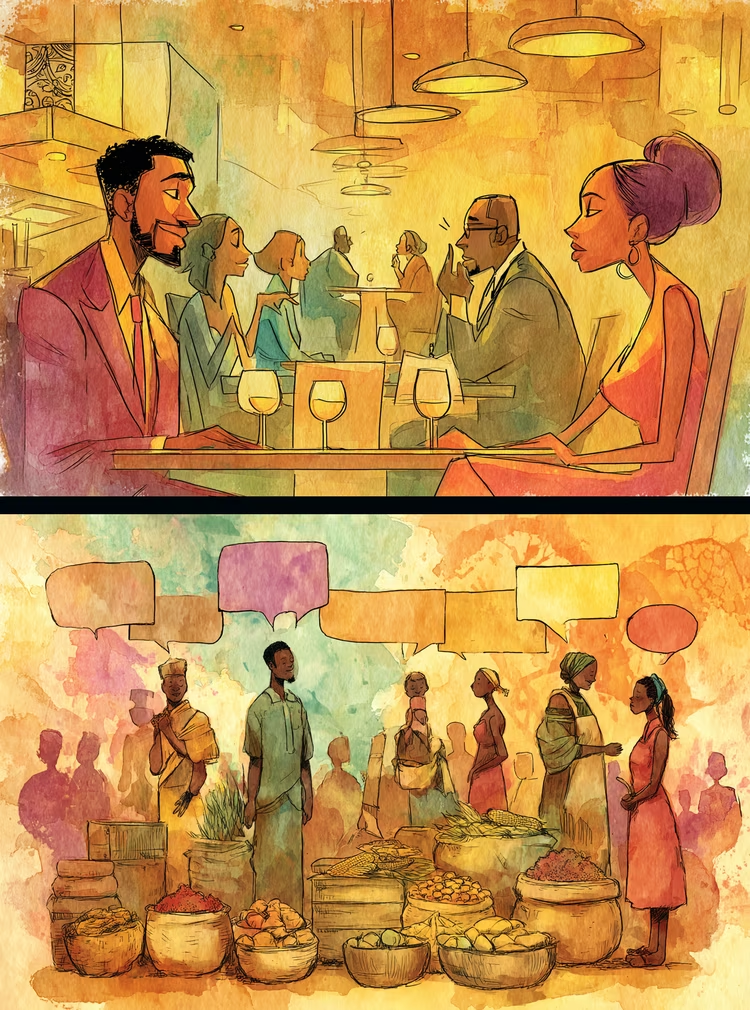

My sister and I had barely settled into Lusaka's newly opened restaurant when a conversation about language would challenge everything I thought I knew about my own voice. An interracial couple at another table struck up a conversation with us about Zambia's tribes and languages.

She asked us why we spoke English to each other. Neither my sister nor I had a concrete reason—we just did. The conversation moved to colonisation and independence in 1964, when English was chosen as Zambia's official language to prevent tribal divisions: One Zambia, One Nation.

This discussion has long intrigued me. English has become both a bridge and a barrier in modern Zambian identity, creating invisible class divisions while enabling global connections.

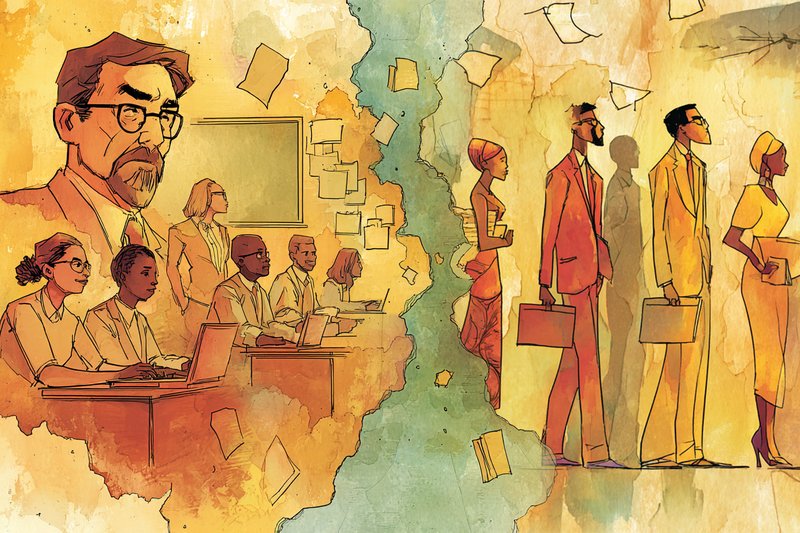

How English Created Class Divisions

There's a young woman on TikTok who talks about how she used to brag to other kids about her fluent English, but now regrets being that person and wishes she could go back and tell her younger self to learn her native tongue instead.

Speaking English meant an increased chance of employment—that mentality spread to the next generation.

When I was young, "Utubasungu" would be spoken with impressed voices when someone wore formal attire. To my elders, it meant excellence and honour. Translated literally, it means "White people," but at its core, "Embracing whiteness."

High- and Low-Class Citizens

A Twitter user lamented that her parents never let her play outside with other kids, leaving her unskilled in Zambian languages. She became the "English-speaking cousin"—a well-known joke among Africans fluent in English but not their native tongue.

This reminded me of walking through Chilenje, where kids played street soccer, speaking only pure Nyanja. Compare that with Woodlands, where children's play mixed English with bits of Nyanja. In Ibex, fewer children play in the streets—their attention is shifted to digital devices, and the language most spoken on those devices becomes their strongest.

The area determines the language you'll speak through code-switching, though some prefer their native language over one that their community rarely uses.

I was educated about history through English and saw British patterns in my elders: afternoon tea, cheek-kissing greetings. One aunt still has a subtle British accent despite never visiting England, though she knows two native languages.

School and Social Pressure

I attended a school where we only spoke English from the gate to the bell. Heading home, my neighbourhood friends would slowly switch to Bemba once we distanced ourselves from school. It wasn't strict enforcement—just a mindset the school placed on us.

The moment my school friend called out in English, my tongue betrayed me. I switched languages mid-stride, abandoning my neighbourhood friends' Bemba conversation. The mockery that followed when my school friend left—"Ooh Ichisungu"—stung because it revealed a truth: I was becoming someone different depending on who was listening.

We were so conditioned that when school friends met outside, speaking our own language felt new and funny.

How the World Sees African English

Foreigners are often impressed by how well we communicate in English across Africa. The U.S. president once complimented the Liberian president's fluent English, suggesting a lack of awareness about whom he was addressing.

My Canadian screenwriting mentor asked where I learned to speak "such good English." Knowing that the question would come after seeing 'African' on my application, I explained it was education and television consumption—and that I'm one of many.

A British man travelling from Tanzania to Zambia noted he knew a railway worker was Zambian because of her good English. Was he implying one culture was more versed in his language than another? This circles back to positioning English speakers in a higher regard.

English in Multilingual Zambia

Clear communication is more important than misunderstanding, and English eases translation between our country's many languages. Think of texting someone—when the message is misunderstood, you call to clear things up. English is like that clarifying phone call.

As digital translators improve, one might wonder if English will remain our default bridge language, or if people will stick to native tongues while technology handles translation.

As I write these words in English, reaching readers across continents, I'm both perpetuating and questioning the very system I critique. The reality is complex: English opened doors for me professionally and globally, yet it also created distance from my cultural roots and community.

The challenge isn't simply choosing between English and our native tongues—it's learning to navigate both worlds authentically. We must recognise that language shapes not just communication but identity, class, and belonging.

For Zambia to truly embrace its multilingual nature, we need systems that value all our languages equally, not just in policy but in practice. This means creating spaces where speaking Bemba, Nyanja, or any of our 73 languages carries the same prestige as speaking English.

The goal isn't to abandon English—it's a valuable tool for global connection. Instead, we must dismantle the mentality that equates English fluency with intelligence or worth. True linguistic freedom comes when we can code-switch naturally without shame, when children can play in the streets speaking their mother tongue without it limiting their future opportunities.