Kenneth Kaunda and the United National Independence Party (UNIP) launched the Chachacha campaign - a strategic movement of mass civil disobedience. While colonial forces responded with brutal crackdowns, the campaign's disciplined non-violence prevented a racial war and forced Britain back to the negotiating table.

The word Chachacha was the name of a popular community dance that was turned into a chant for freedom during the 1960s in colonial Zambia, then called Northern Rhodesia. The name became a movement to end the rule of the British Minority and champion the giving back of power to the people of Northern Rhodesia.

Origins of the Chachacha Riots

During the colonial era, many African countries were gaining independence, and the colonial authorities in Northern Rhodesia were becoming increasingly aware of the changes ahead. In the early 1950s, segregation and discrimination were pervasive in Zambia, and young black freedom fighters such as Lewis Changufu were organising strategic boycotts against these systems, compelling colonials to treat every black Zambian as an equal.

The 60s had arrived, and Independence was on the horizon. The United National Independence Party (UNIP) and its president, Kenneth Kaunda, were in negotiations with the British on having fair political rights in parliament. With the constitutional proposal of the 15-15-15 electoral scheme, which promised Africans 15 “lower roll” seats in parliament, and 15 “upper roll” seats for the British, and 15 “national” seats elected by both. The British believed that this move would demonstrate their commitment to giving Africans an opportunity to achieve equality in the country. But the UNIP saw through the scheme, which favoured the white minority by having separate ballot papers and racial classes, fueling further segregation.

UNIP did not accept the proposal. After Kaunda's non-violent initiatives brought no results, frustration grew among party members, some demanding more forceful action. At Salisbury airport, Kaunda underwent a thorough search, during which his conference notes were taken. He described the experience as deeply humiliating and responded by declaring a 'practical war'—a committed resistance to British rule, though still rejecting violence.

The Chachacha Campaign

Keneth Kaunda always asked the people to be “Patient, non-violent in thought, word or deed.” However, on 9 July 1961, at the Mulungushi conference, Kaunda gave a speech to more than 3,000 party delegates, where he announced the removal of the word “Patience” but still emphasised the importance of remaining non-violent.

As he spoke, approval and repeated shouts of Chachacha were heard from the crowd, to the confusion of some who didn’t understand. Kaunda simply stated that everyone, including the Queen of England, would soon dance to the music until victory was won.

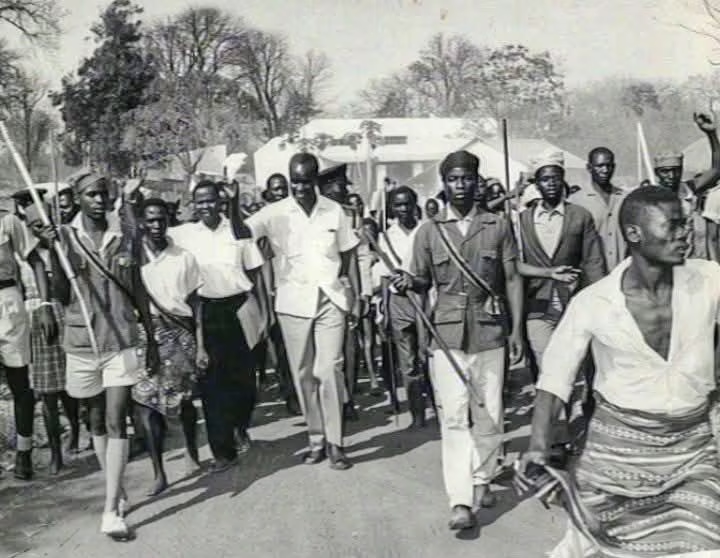

With Lewis Changufu at the helm of the Chachacha campaign, UNIP members initiated mass burning of identification certificates in areas like Samfya, with children delivering ashes to District officers, declaring “President Kaunda sent us”. Mass disobedience against colonial rule was underway, including the destruction of bridges, roads, government property, and the closure of schools.

The British response to the Chachacha Campaign

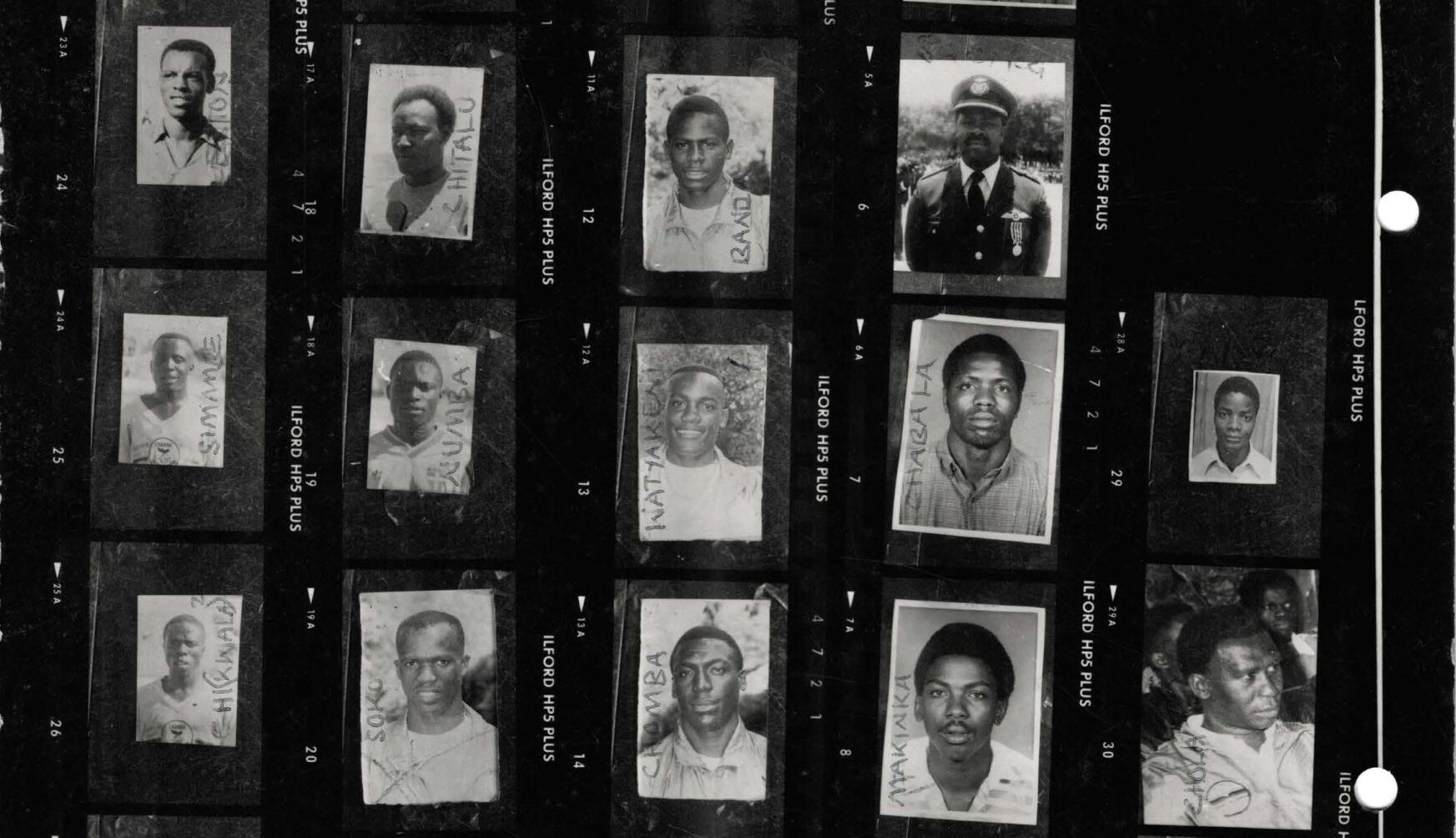

The colonials responded by committing atrocities, including beatings, torture, village destruction, and mass arrests of over two thousand people. The UNIP published papers detailing these atrocities, and in turn, the British compiled their own manipulated papers of “Disturbances” but avoided including the UNIP to prevent embarrassment in future negotiations.

Though the campaign continued its disciplined resistance, clashes only occurred with security forces, and European civilians were never attacked. By November, Governor Hone announced restored order because the non-violent leadership prevented the movement from causing racial warfare.

The Aftermath of the Chachacha Campaign

The campaign brought about political changes in leadership, prompting renewed constitutional negotiations. Following the major elections in 1962, UNIP secured a majority of votes and consequently gained most government seats.

By 1964, another election was held and UNIP had a decisive majority win, which then led to Keneth Kaunda being elected as Prime Minister and the Independence of Northern Rhodesia on the 24th of October 1964.

Lewis Changufu, the campaign's chief coordinator, exemplified the loyalty that Kaunda commanded among UNIP members, praising his determination and clear thinking, which kept their focus on the struggle for a society that could be achieved without hate or bloodshed.

The Chachacha campaign proved African political maturity in a time of racial hate and inequality. It proved that unity could be achieved without descending into violence, and that same movement of non-violence has been reflected in today's politics.