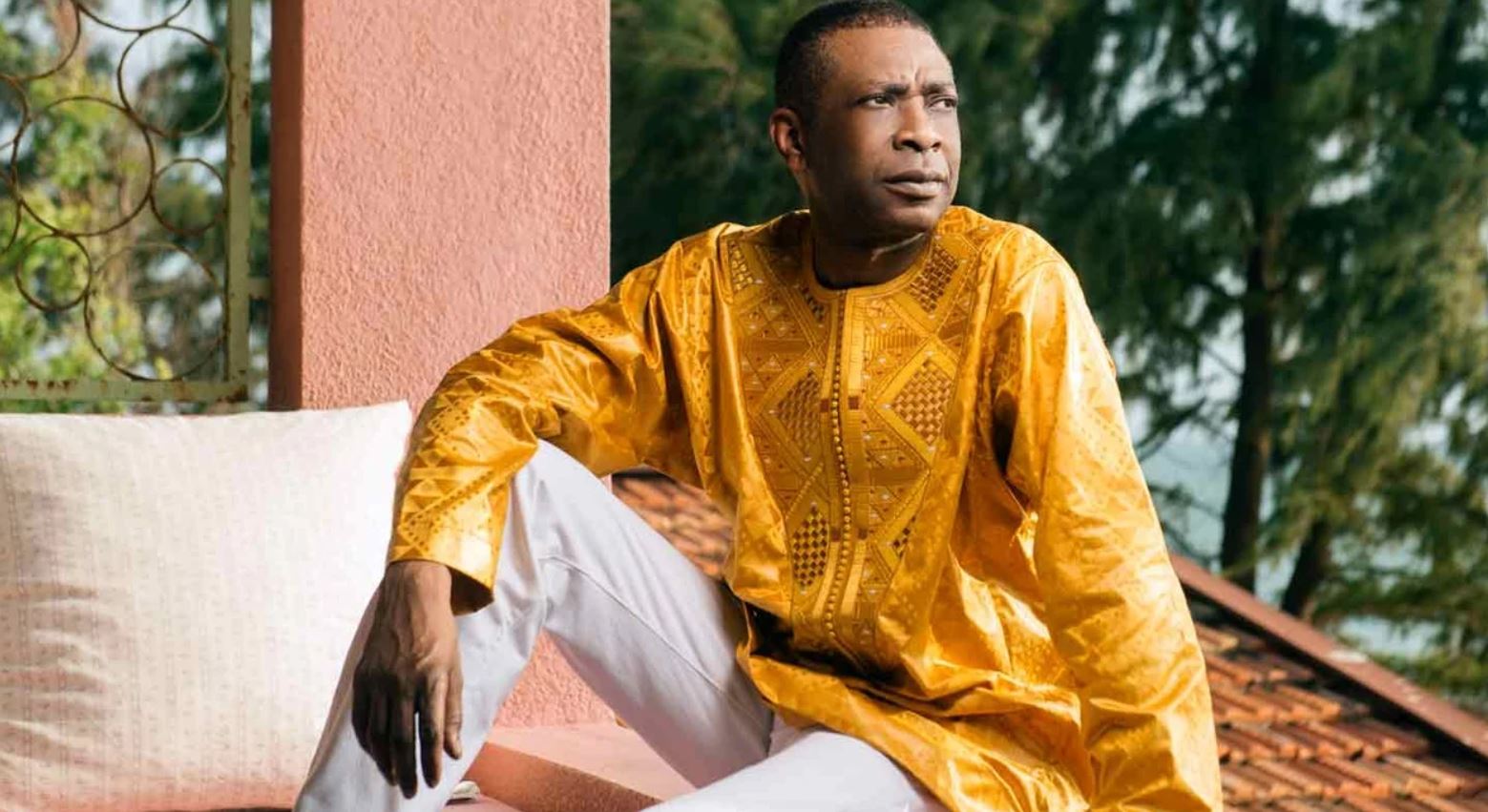

The voice that’s coming from my laptop isn’t the one I’d expected to hear. You’d think someone that can move multitudes of people at the turn of a few dials while broadcasting bass at near-deafening decibels would sound more… godlike. But he gives the impression that he’s as mortal as they come.

Sebastien Dutch or Julius Mwewa, as close friends and family know him, is a DJ/producer that creates Afro house and Afro tech. We’re not in an artsy café or Sebastien’s studio. I’m in my study and he’s beaming from his living room, like a being transmitting from a distant starship.

When I ask him about his origins, he begins what could easily turn into a TED Talk about the Dragon Ball Z franchise. “They’re focusing on a multi-verse approach now,” he says damn-near geeking out but playing it cool, gauging whether he can show me his true form yet. “And each universe has a god, and each god has an angel”.

Unlike the angels he speaks of, he’s wearing the colours of Manchester United—the Red Devils. “I’m not the villain in this story,” he says ironically when answering my question.

He begins with his high school days. “I was always like… the odd kid. When everyone was listening to Lil Wayne, I listened to Linkin Park. But I think because of [external] pressure, like rock music isn’t really good for you… teen angst… I had to find something else.”

It was around that time he watched Daft Punk’s ‘One More Time.’ He was not only drawn to the video’s interstellar anime themes, but also to the electronic synth and blends of funk scattered on the song’s production. The clincher happened soon after, when electronic music producer, deadmau5 (pronounced “dead mouse”) had his song ‘I Remember’ on heavy rotation. “Which I think is one of my all-time favourite songs,” Sebastien says enthusiastically.

He then started diving into the deep house end, discovering European producers like David Guetta and South Africa’s DJ Cleo. But just listening to the music wasn’t enough.

“At that time, one of my closest friends, DJ Drill, was already making music and had a makeshift studio,” he says. Drill was crafting hip-hop beats then, and he taught Sebastien Dutch the workings of VirtualDJ. Sebastien, in the meantime, was also learning to produce his own house music from YouTube tutorials.

The two soon started playing at parties in Ndola and Sebastien later began to earn his stripes on the decks at Circles, pestering DJs to give him a chance at using real equipment at the popular nightclub.

“In the beginning, people weren’t very responsive but there were a few DJ Cleo tracks that would play on Channel O, and people started to get into that kind of house,” Sebastien says.

Around 2009, he moved to Lusaka and got his first real gig at the UNZA Student Centre’s Club Focus, playing short sets between DJ changes and practicing before the undergrads filled the dance floor.

When talking about his influences, he mentions the late DJ LBC with fondness. LBC was a radio personality and DJ at Lusaka’s Rock FM, and somewhat of a mentor to him. “I didn’t really deal with his death,” he says solemnly. They met after Sebastien and his friends orchestrated a guerilla Twitter campaign to coax LBC into getting him on a Big Brother Eviction Party lineup. “We basically harassed the guy, let’s be honest!” he says clapping his hands in amusement. The friendship not only produced fond memories, it also led to collaboration on Zambia’s first house album, Power of the Drum.

Sebastien also cites afro-jazz and kalindula artist, James Sakala as an influence on his personal philosophy. When I ask him about what he’s learned from James, he pauses to think and then says, “Be true to yourself. Be true to your sound. You don’t always have to bend as an artist”.

It’s that same resistance to the norm that later led to a victory in the AXE DJ Challenge in 2017. The popular deodorant brand took music submissions from DJs around Africa and Sebastien won the competition. He got to play his tunes in Ibiza, rubbed shoulders with household names like Black Coffee and Da Capo, and came away with valuable lessons.

“I learned to be in touch with the sound… to be more creative with it… not just to make hits for the radio or the club,” he says with confidence.

Sebastien Dutch keeps working on his craft and it has earned him some international recognition, releasing music on South African imprint Iklwa Brothers Music and also becoming one of Zambia’s Budweiser ambassadors. But, like most people, the pandemic has changed his everyday life.

“It’s affected my work in every way. But we’ve discovered other avenues to share our art,” he tells me. Live streaming and radio have helped him keep in touch with his audience.

I get a sense of where he’s been and what he’s done, but this makes me think about the actual origin of his name. He tells me the ‘Sebastien’ half was inspired by Sebastian Ingrosso from Swedish House Mafia. And ‘Dutch’ is a reference to Netherlands, where some of the best progressive house hailed from.

Today he has some regrets about choosing a European and not an African name. “The drive to be out there is what pushes us to adopt these names,” he says about young artists’ inherent need for international appeal. He sometimes adds the tags “Ushi Beat Mix” or “Ngoni Beat Mix” to his songs to hint at his heritage.

When I ask about why people should listen to his music, he tells me that it’s not just about him. “Throughout my career I’ve been trying to get people to understand what house music is. I’ve mentored DJs like Ms Selfie. Now she’s one of the biggest DJs in the country. And I’m still trying to push other DJs and musicians.” Part of this push has been working with Dennis Red on a house remix album titled House of No Names. The idea was to give lesser known artists and DJs a chance to get their music heard on a larger platform.

Though he isn’t necessarily godlike, his humility is refreshing. But Sebastien Dutch is doing everything to be omnipresent. “I’ll be very honest with you, as electronic musicians in Zambia we get recognition outside Zambia, which is super cool. But we don’t get the same recognition here.” Sebastien says he’d like to change that. “Why must we wait for outside recognition before we recognise our own artists?”