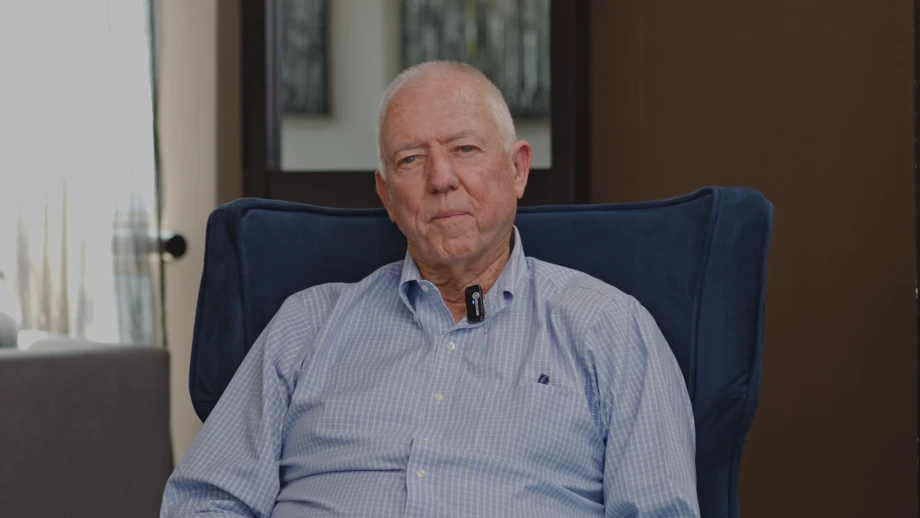

Dr Denny Kalyalya has vivid memories of several events from his adolescence and youth and he can’t help but start off our conversation by sharing some of them. One moment in particular stands out for DR Kalyalya who is the Governor of the Bank of Zambia. When he was in Form 3 his mother asked him a question that struck him. “What if you fail?” This was with regards to his schooling. Dr Kalyalya performed well in school and failure hadn’t crossed his mind. However, the question sparked something in the young Denny and drove him to remain serious about his studies. Despite the importance of this question from his mother, Dr Kalyalya makes a point of not being guided by the fear of failure, as I later discovered during our chat.

Born and raised in Monze in Southern Province, herding cattle was Dr Kalyalya’s preferred chore. This was a tactical choice. While out in the bush he could study as the cattle grazed. Dr Kalyalya avoided working in the field as this did not allow him to read. He would often climb a tree and study while perched on the sturdy branches as the animals grazed below.

After completing his secondary education at Kalomo Secondary School in 1975, Dr Kalyalya began six months of military training in the National Service. After his time in the National Service Dr Kalyalya was informed he had been selected for employment with Zambia Consolidated Copper Mines (ZCCM). He stopped to stress a point: “We don’t pay tribute to ZCCM but they were very active in education. ZCCM played a very important role in human development and human capital in Zambia.”

Dr Kalyalya opted for a position as an accountant with ZCCM in Chililabombwe and settled in to his new role and was preparing for further accountancy training but a life of academia was calling him. Having done well in his final exams the doctor-in-the-making was offered a place at the University of Zambia (UNZA).

A choice had to be made – stay in a reliable job or study for a bachelor’s degree. The decision weighed heavy on him and some of his colleagues could see that something was bothering him. He recalls one colleague that advised him, “Young man, if I was you I wouldn’t waste any time. Go to university.”

The young man headed to Lusaka to begin late registration for his first year of university (his peers were already one month into the process). Despite being told that he was too late at the various stages, he managed to complete his registration in the nick of time. The final step in the process was securing his bursary, which he got with only minutes to spare before registration was closed for good that year. And so in 1976 Denny Kalyalya began his studies at UNZA. After graduation he continued with his education, enrolling in the newly created master’s programme and subsequently began lecturing at UNZA. He enjoyed teaching but he describes his first lecture as “one of the most difficult things I ever did.”

His master’s was partly focused on regional planning and urban development. Following the completion of his master’s, Dr Kalyalya was awarded a Fulbright Scholarship for his PhD studies at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. The recently wed Dr Kalyalya arrived in the US with his wife, where they stayed for seven years and had both of their children. Denny Kalyalya studied International Economics and his dissertation focused on how regional integration can promote development. His reason for this was simple: “I wanted to do something of relevance to my country.” Dr Kalyalya always intended to return to Zambia, much to the surprise of some of his Zambian colleagues. But he argued: “I went to the US as an adult and I already had a home in Zambia.”

Dr Kalyalya returned to his position as a lecturer at UNZA and was also appointed Assistant Dean – Postgraduate. Then in 1995 Dr Jacob Mwanza, Governor of the Bank of Zambia (BoZ) at the time, asked Dr Kalyalya to join the central bank as an Economic Advisor in the Economics Department. Dr Kalyalya had concerns about leaving his students and leaving a gap at the country’s highest learning institution. However, Dr Mwanza told him, “Your country needs you here now.” At the time BoZ had many expatriate advisors and was seeking to hire more Zambians. Dr Kalyalya finished out the academic year before joining BoZ. A year later he was appointed to the IMF as a special appointee in Monetary Exchange Affairs Department and the African Department. Following this he returned to BoZ and in 2002 was appointed Deputy Governor – Operations, a position he held for eight years. He then served as Alternate Executive Director at the World Bank for two years following his appointment in October 2010. However, his time with BoZ was not over. Though as far as he knew, “I had completed my tour of duty with the Bank.”

In 2015 Dr Kalyalya was appointed Governor of the Bank of Zambia. He calls this his “second coming.” Dr Kalyalya took the reins at a time when Zambia was dealing with high inflation and a weakening kwacha. He likens those days to the current economic times in Zambia.

Needless to say, heading the central bank comes with the kinds of pressure that most people can only imagine and expectations are high. “The decisions we make as a central bank can have an immediate effect on people’s lives. It’s not easy because the decisions you make have implications. And sometimes there are implications of not making a certain decision and the consequences could be even worse.” Dr Kalyalya continues, “Economics is not an exact science. That’s one of the challenges of social science.”

Despite the economic challenges Zambia currently faces, Dr Kalyalya maintains a positive outlook. “Zambia is richly endowed. We have resources that others don’t have. So it’s a question of managing those resources effectively, including human resources. Young people are a resource but are not seen as such…We have been talking about diversifying the economy for a long time but we’re still dependent on copper.”

Dr Kalyalya argues that Zambians often focus on money or the lack of money but believes planning is paramount. “Money without a plan is a problem. We need to have a plan and we do: the Seventh National Development Plan.” He goes on to say, “We should be more forward looking and avoid crises, rather than focus on solving them. As an institution we have adopted a forward looking policy. What happened yesterday, important as it is, cannot be changed. But we can learn lessons from the past to prepare for what is to come.”

Listening to Dr Kalyalya talk about his work, a sense of duty becomes apparent. “The government paid for my education so I owe it to the Zambian people to work for them…I care about my country. I’ve been privileged to be in this position and would like to leave Zambia and this institution better than I found it,” he tells me. This mindset also impacts Dr Kalyalya’s leadership style. As he explains it, he got to where he is today because various people took a chance on him. “I’m here because someone gave me the opportunity and I’d like to see my colleagues and others succeed,” he says with a smile.

Dr Kalyalya describes the Bank of Zambia as a “knowledge institution.” As such, he believes there must be room for open dialogue and no one’s ideas should be disregarded simply because they are a less senior member of the team. He adds, “I like my colleagues to express themselves freely so that we address issues properly. I don’t want people to work in fear and feel they must avoid me. If you fear your boss you won’t do your job well.”

At this point we have gone far beyond our allotted time but Dr Kalyalya wants to leave me with some words of advice for the Zambian people. “Be who you are. Everyone has a purpose in life and that’s what we are all searching for. Fear God. In the grand scheme of things life is short. Do what you can to make other people happy in the time that you have on Earth.” He further advises the youth to think beyond their present circumstances and to always remember they can take on whatever challenges they face.

To those focused on money, or a lack thereof, he says, “Banks don’t give money. They buy ideas. If you have a good idea, the money will follow.”

Earlier in our conversation Dr Kalyalya compared Zambia’s economic challenges to a storm and he returned to this analogy. “We’re in a storm but we must keep moving. Beyond the storm it is quiet and you’ll be surprised by what you’ll find.”