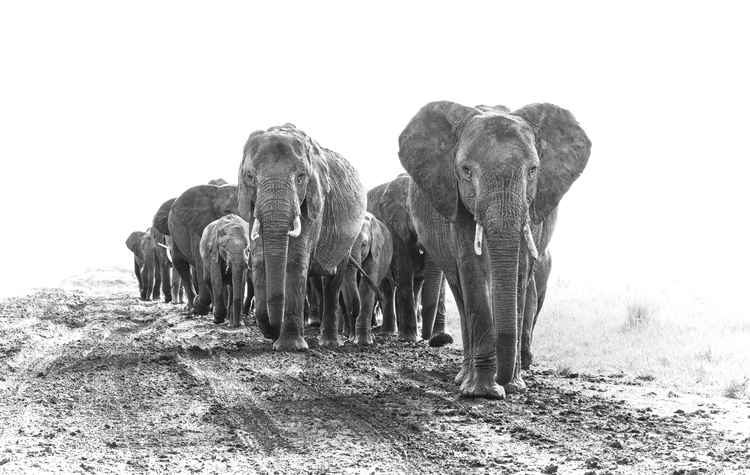

On 26 August 2024, Namibia’s Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism announced that the country plans to cull over 700 wild animals, including elephants and zebras, in response to the worst drought the country has experienced in 100 years. The meat will be distributed to people struggling with food insecurity in the country. The animals marked for culling include 83 elephants, 30 hippos, 60 buffalo, 50 impalas, 100 blue wildebeest, and 300 zebras.

Less than a month later, Zimbabwe followed suit, announcing plans to cull 200 wild elephants to feed communities facing severe hunger during the worst drought in four decades. Zimbabwe’s environment minister announced that the ministry is in discussions with ZimParks to cull and mobilise initiatives to dry the meat, package it, and ensure it reaches communities that are at risk of malnutrition and other famine-related conditions due to limited access to food and protein.

Humankind must learn to understand that the life of an animal is in no way less precious than our own. — Paul Oxton

Awareness

My son has a collection of National Geographic Kids books, each dedicated to a single species—something his grandmother so kindly gifted him. He loves them and flicks through them to keep himself entertained for hours. One day, he was reading the book on elephants. He approached me and proudly recited facts: where they live, how many sub-species exist, and that they weigh 300 times more than him! His enthusiasm was contagious.

Then he showed me the endangered scale, which was highlighted orange, indicating that they are endangered (red is critically endangered), and went on to explain that people destroy their homes and also kill them for their tusks. My heart sank.

He is five years old.

On the one hand, I was so proud; we watched countless wildlife documentaries, and he had the privilege of encountering many African species in person. His awareness and understanding were perceptive, clearly showing concern for other living species—more than most people, let alone his peers. On the other hand, the bigger picture comes into play, and it is on days like this when optimism fades away. It had only been a few hours since I read the aforementioned article; the timing was jarring.

Bigger Picture

These articles saddened me quite profoundly.

The devastating drought in Namibia and the rest of Southern Africa is not an isolated event; it is part of a larger global pattern of environmental crises exacerbated primarily by human actions: bigger-picture thinking. While this move may seem like a practical solution in a dire situation, it raises profound ethical questions about the relationship between humanity and the natural world. I should note that this article is not an isolated event; it reflects a culmination of thoughts and emotions that have built up over time, with this particular piece igniting something within me.

Overpopulation, unsustainable agricultural practices, deforestation, overfishing, industrial pollution, illegal wildlife trade, plastic consumption, waste mismanagement, and rising sea levels are just a few of the many I came up with in seconds. They have all contributed to the disruption of natural cycles and the depletion of terrestrial and marine ecosystems in some way. While the immediate cause of Namibia’s drought may be climatic, the underlying drivers are deeply rooted in how humans have altered the planet.

This is a fact, not an opinion.

The Namibian government’s decision to cull these animals is supported by international organisations, including the United Nations, under the Convention on Biological Diversity, which permits bushmeat consumption from sustainable sources. However, those familiar with Africa’s wildlife management know that this area is grey and murky. Much like the justification of professional hunting, which claims to target only the old, weak, and diseased animals, the rationale for culling often fails to hold up under scrutiny. In reality, these practices can lead to further imbalances in ecosystems and the unnecessary suffering of animals: once again, a fact.

When such credible and influential organisations exhibit even an iota of support for an incident like this, it normalises these types of strategies and diminishes the long-term impacts. As the saying goes, “Give a finger, and they’ll take the whole hand.” Another argument justifying the cull is that it could reduce human-wildlife conflict and prevent the animals from suffering due to the drought—I cannot express the emotional rollercoaster this statement takes me on. In contradiction to this statement, wildlife is inherently resilient, far more so than humans. Given time and space, these animals can adapt to changing conditions. The notion that we must intervene to “save” them from suffering is rooted in a misunderstanding of nature’s processes.

Burden

Although I do not have a solution to the drought crisis, I do not condone human suffering either. However, I admit that I am also talking from a privileged position. In all honesty, this article is an outlet. I am empathetic towards those suffering, as I am to similar events in other parts of the world, but accountability falls to us. This is OUR responsibility: the government, NGOs, private and international aid, and those who volunteer and help—not wildlife. We have developed the notion that human beings take priority over everything and every other living species.

My concern is the injustice to innocent wildlife. Are we to believe that all other potential solutions have been exhausted? Are we really solving the root problem through this process? What about foreign aid? Is the situation so dire that the only recourse is to make wildlife pay the price for a crisis humans have contributed to? Do we realise how short-sighted this is? Would we make a similar sacrifice if the roles were reversed? I’m not suggesting that we should, but it’s the principle.

The fact that we have turned to culling animals—lifeforms that had no hand in creating this crisis—suggests a failure to fully explore and implement alternative measures. It’s a harsh reminder that the burden of human-induced crises often falls on the innocent, including the wildlife that plays a crucial role in our planet’s ecosystems.

I engaged in discourse with several stakeholders in the conservation space about this, and this is a summation of their stance:

“Whatever actions are taken concerning animals will inevitably impact humans as well. These animals and their habitats contribute significantly to ecotourism in the region. Governments must search for alternative solutions that benefit both humans and wildlife because, in the end, whether we fail or succeed, it will be in unison.”

“Animals are there merely as a means to an end. That end is man.”

— Immanuel Kant

About the Author & Disclaimer: Amish Chhagan (Chags Photography) is an award-winning wildlife and conservation photographer. The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author.

Learn more about the author - check out his website or Instagram page.