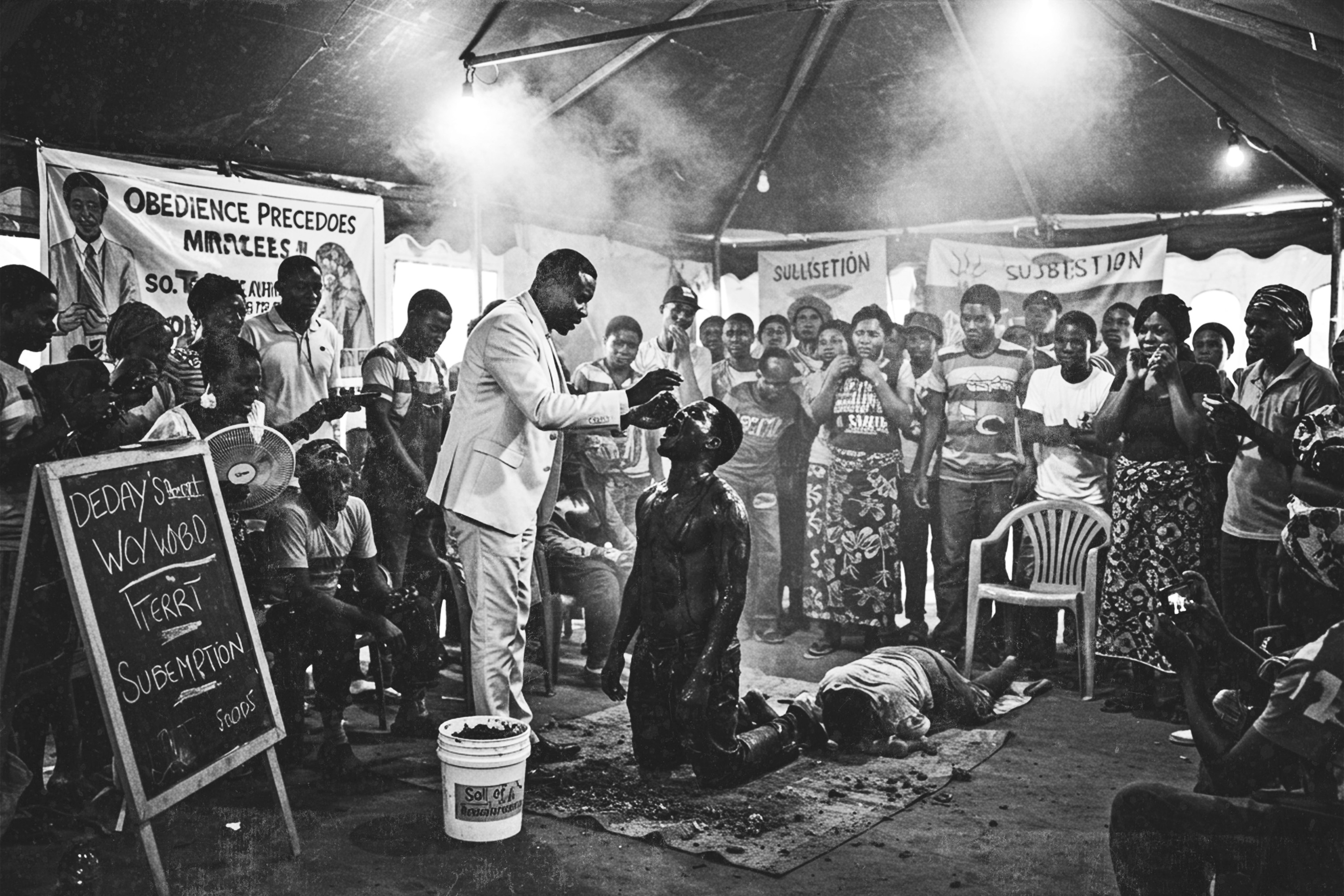

For many Africans, the idea of "black tax" is more than just a term—it’s a lived experience. The expectation to financially support extended family members once you’ve achieved financial stability can be both a source of pride and a cause for stress. Rooted in communal values, it embodies the spirit of ubuntu—"I am because we are"—but in modern times, it has sparked debate over its fairness and sustainability.

The concept grabbed international attention last year when Kenyan social media personality Elsa Majimbo shared her frustration with it in a now-viral video. She criticised the expectation to shoulder family financial responsibilities, recounting her own family’s experiences. Her blunt remarks resonated with some but outraged others, especially those who view black tax as an integral part of African culture. While the backlash was swift, Majimbo’s rant reignited a larger conversation about this deeply ingrained practice. In Zambia, financial literacy expert and consultant Lyapa Mbewe has been critical of black tax and has spoken out against putting yourself in a position where you are largely or solely dependent on family for money. "Your children are not a retirement plan," has been one of her criticisms of relying on black tax to survive.

Black tax, at its core, is about lifting others as you climb. It’s an unspoken contract passed down through generations, particularly in African families where systemic inequalities have left many without generational wealth. For some, supporting siblings’ education, covering parents’ expenses, or helping relatives in need is an act of love and solidarity. It’s seen as a way of giving back and keeping the family unit strong.

However, it’s not without its challenges. Many young professionals have expressed frustration at the financial strain it can place on their lives. Imagine finally landing a good-paying job, only to realise a significant portion of your income will go towards responsibilities you never officially signed up for. For some, it feels like a never-ending cycle, making it difficult to save, invest, or achieve personal financial goals.

The reactions to black tax often vary by generation. Older generations tend to see it as a moral obligation, while younger Africans are increasingly questioning its impact on their financial independence. Social media has become a platform for these conversations, with hashtags and memes shedding light on both the humour and the harsh realities of black tax.

It’s worth noting that the debate isn’t about rejecting family values. Rather, it’s about finding balance. Should one person carry the weight of an entire family’s needs? And at what point does financial support shift from being a helping hand to fostering dependency?

As these discussions evolve, some families are exploring alternative approaches. Open conversations about financial expectations, setting boundaries, and creating sustainable ways to support each other are becoming more common. For example, some families pool resources for investments that benefit everyone, such as starting a business or funding education for multiple members.

Elsa Majimbo’s rant may have been controversial, but it wasn’t unique. Her frustrations reflect the thoughts of many Africans navigating the pressures of black tax in a world where personal aspirations often clash with cultural expectations. The key takeaway? Black tax isn’t just a financial issue—it’s deeply tied to identity, values, and the push-and-pull between tradition and modernity.

At its heart, black tax is a reflection of African resilience and interconnectedness. But like any tradition, it must evolve to remain relevant. Finding a way to honour family ties without sacrificing individual well-being is the challenge—and perhaps, the opportunity—of this generation.