Here’s something to think about; in the jungle, the mighty jungle lions do not sleep at night. Lions are nocturnal and often spend their nights hunting. Also, lions don’t live in the jungle. With few exceptions lions are not found in tropical rain forests or dense jungles. They live on grassy plains, savannas and semi-arid plains of sub-Saharan Africa. Facts like these make you wonder how much you really know about lions. For example, did you know that in the last two decades Africa has lost half its lions? The threat to lions is immense, compounded by several factors including human-wildlife conflict, habitat loss, the illegal bush meat trade, which results in snaring and prey depletion. Then there is the increasing trade in cat skins and bones.

The trade in lion body parts, and especially the trade in bones from Africa to Asia, is cause for concern. Lion bones are largely sold to Asian markets for use in virility products and traditional medicines. The trade in bones to Asia is thought to supply the substitute ‘tiger bone’ market and began in February 2008 when CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora) first issued permits allowing the trade in South Africa. Since then the trade has grown.

In mid-2018 the South African Department of Environmental Affairs made the controversial decision to increase the annual quota of legal lion bone exports to 1,500.

They cited several reasons including a “growing stockpile of lion bones in South Africa” and that “the lack of a discernible increase in poaching of wild lions in South Africa” even though there appears to be an increase in poaching of captive bred lions for body parts (heads, faces, paws and claws). Their logic was simple, “if there is ongoing demand for lion bone and the supply from captive breeding facilities is restricted, dealers may seek alternative sources, either through illegal access to stockpiles or by poaching both captive bred and wild lions”.

But why does this matter to Zambia? Well, for starters South Africa is one of only seven countries in the world that has substantial lion populations. Zambia is another. Many conservationists are of the belief that an increase in the South African lion bone quota will increase the poaching of wild populations of big cats. Recent studies by organisations such as TRAFFIC and the Environmental Investigation Agency have shown that most of the legal lion bone trade is feeding into the South-East Asian, tiger bone market. These bones are used in traditional concoctions considered to have medicinal properties and are often misrepresented as tiger bones to consumers; this has also been shown to be exacerbating the illegal trade of the endangered tiger. From such evidence it would be logical to predict that the increase in the quota and hence the supply to this market will not only affect wild lion populations but also other big cat populations in all the places they exist. The increase in legal trade of lion products would make it easier for unscrupulous individuals to launder wild lion (or cheetah and leopard) products into the captive bred and legally acquired consignments.

So, it’s safe to say it’s not just South Africa’s lions at risk. According to the South African Department of Environmental Affairs quota report there has been an increase in the poaching of captive bred lions in South Africa (but not wild populations), however this is in a country with a relatively large captive bred population and very few ‘wild’ populations as all of South Africa’s national parks are fenced . A country like Zambia has most of its lion population in the wild and is already experiencing significant instances of big cat poaching and trafficking. In short, an increase in the legal trade in lion bone product, will not reduce the pressure on wild lions but most likely increase it over time.

The trade in big cat products is not a new one. The trafficking of body parts for African traditional medicine is also thought to be on the rise. Even locally some believe that big cat products can make them wealthy. Something known locally as “blasting.” Whether this is true or not is irrelevant like the tiger bone trade the mere belief is enough to result in the destruction of populations across the continent.

The lion bone trade signifies a much larger problem. Finding solutions requires population estimates, rarely available due to funding and logistical challenges. Wildlife Crime Prevention (WCP) in partnership with Zambia Carnivore Programme and funded by the Lion Recovery Fund seeks to be part of the solution with its study into “the scale the trends, patterns and drivers of the illegal wildlife trade in Zambia”

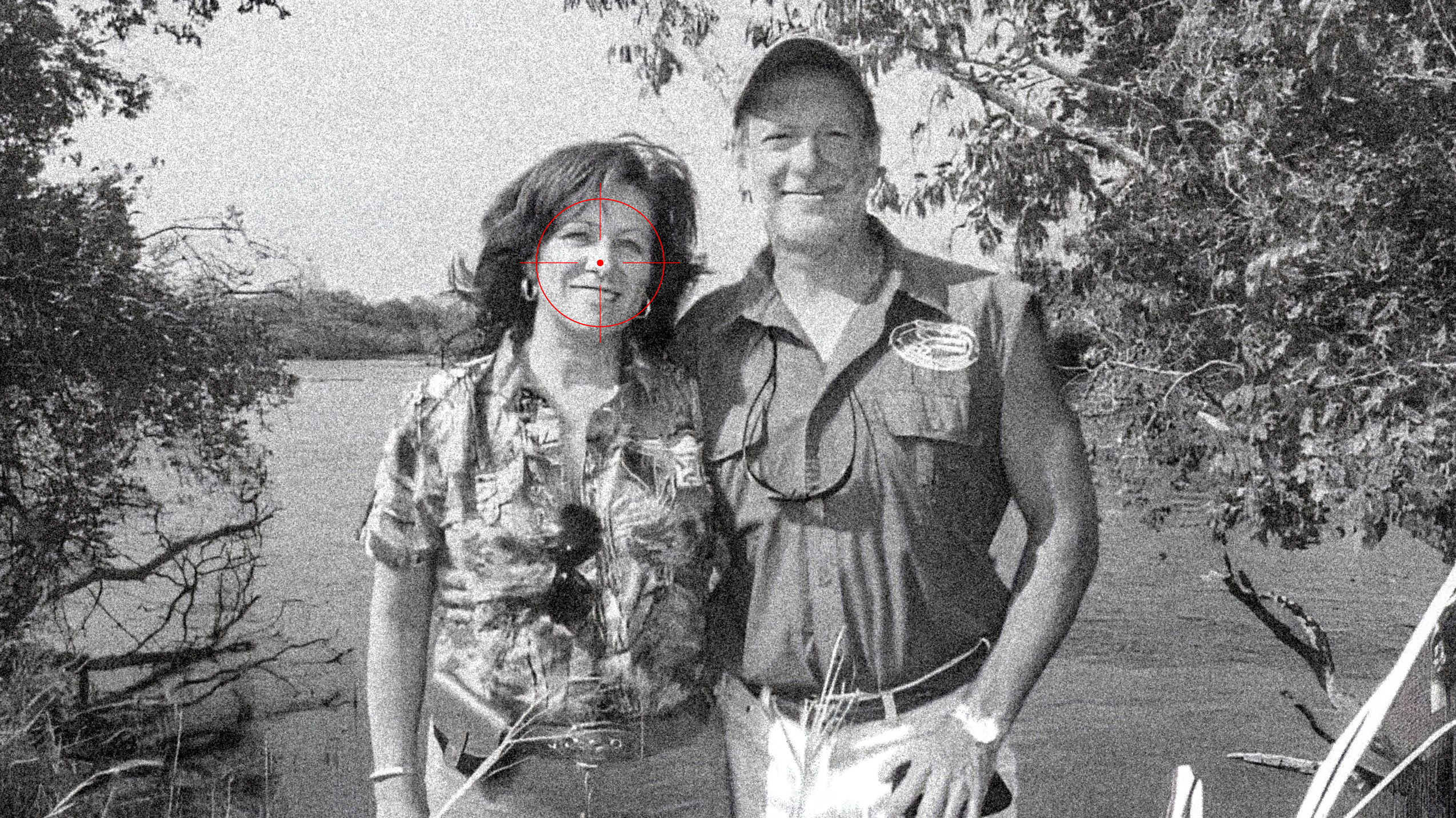

In Zambia, as with several other countries, there is growing evidence of targeted poaching of lions for skins and other body parts, in addition to an increasingly severe threat to leopards associated with poaching for their skins. This project aims to improve the conservation of big cats by gaining a better understanding of the spatial patterns, scale and drivers of the illegal trade of lion, leopard and cheetah skins in Zambia. Working alongside the Department of National Parks and Wildlife, WCP is undertaking an investigation to identify the trade route of big cat skins, the methods of killing and trafficking and where the products end up. In addition, WCP intends to support the development of a DNA database which will allow law enforcement authorities to better understand which protected area system the product has come from. This data will then be used to inform law enforcement strategy to better tackle this rapidly growing threat.

Unfortunately, there is no ‘one size fits all’ solution to the illegal wildlife trade but with collaborative efforts such as these the battle against the illegal wildlife trade is far from lost.