Experience Ingombe Ilede, one of the least-known tourist destinations in Zambia, but one brimming with historical significance. It is said to have been the site of slave trades and a precolonial trade post. The site is steeped in archaeological history and is a must-see tourist destination as you travel through Zambia.

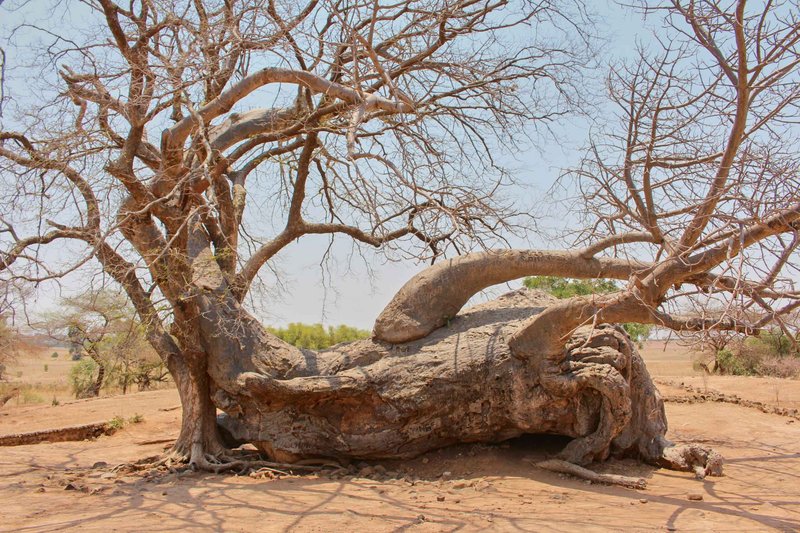

Nestled amongst a sprawling landscape, dotted with the famous trees that the area is named for, one tree stands above, and also lays below. Ingombe Ilede, Tonga for ‘Sleeping Cow’ (due to the uncanny resemblance when seen at a distance), is a massive felled Baobab that has endured and intrigued for decades.

Pockmarked with holes, large and small, and a fair amount of crudely carved-in graffiti, Ingombe Ilede positions itself as the centrepiece of an unglamorous traditional heritage site. With hardened, ash-grey bark, this particular tree looks less like so many of its statuesque neighbours, and more like a stone that can breathe.

As noted by its official status as a Zambian archaeological national monument, the history of Ingombe Ilede is intertwined with that of the region and its peoples. Situated less than five kilometres from the Zambezi river, its landmark-like quality encouraged its utilisation as the site of an opulent trading post, where luxury items like cloth and beads were exchanged for precious copper, ivory, and gold materials.

Archaeological excavations show evidence of a community pre-dating Tonga settlers (as far back 850 AD), although the height of its prominence as marketplace was between the 14th and 15th centuries, where the remnants of those wealthy enough to be buried with seashells, iron ingots and glass beads are consistent with the wares of Muslim traders travelling from the south and along the Zambezi Valley.

Currently, Ingombe Ilede is much more quaint. A little less than 10km from the main M15 road that leads to and from Siavonga and the iconic Kariba Dam, Ingombe Ilede’s off-shoot, dusty gravel trail is flanked by towering trees, gentle rolling hills, and sporadic homes, churches and schools, all covered in a lushness made possible by a much-needed rainy season. Navigating the water-logged pot-holes and small herds of goats or cows is challenging but not impossible, and the occasional pedestrian serves as the best form of guidance, as the only directional signage is at the beginning and close to the end of the journey.

The community in the surrounding locale is small and simple; there is no pomp, no branded merch, no guided tours and an absence of the kind luxury lodgings that are synonymous with Zambia’s other marquee tourist destinations like Livingstone or South Luangwa; the glory is the tree, and the people it shares its space with.

Encircled by a short wire fence that would struggle to keep out a toddler, and manned by the world’s least-busy gatekeeper, the modest fee of K8 per adult belies the subtle majesty of the monument. Bathed in a verdant light passing through its leaves, the abundant wrinkles and dimples strewn across the face of the tree await each visitor like an expectant grandmother, holding decades’ worth stories in every crevice. Approaching the tree soon reveals the entire world that exists in and around it right now. Chirping birds dart from branch to branch, lizards slink across that ground in search of their next respite from heat and hunger, and a tiny caterpillar persistently and patiently makes its way up the trunk.

An afternoon spent having a quiet lunch, with good company, next to a tree that looks like a sleeping cow, is as unremarkable as it is magical. If you put your phone away, have a conversation and truly listen for the response, you’ll find that the entire world, Ingmobe Ilede included, is talking back.